On the first day of school at Mastery Charter Shoemaker, principal Sharif El-Mekki welcomes students and staff not only back to school, but “back to nation-building.” The school serves almost 800 middle- and high-schoolers. Add the adults and the roster nears 900. That’s more than double the population of the world’s smallest country. So, technically, Shoemaker could be a small nation on its own.

But El-Mekki’s call for nation-building echoes beyond the walls of Shoemaker. As the son of Black Panther Party members and activists, he was taught that we are all responsible not just for those inside your home, but for your community. He was also taught that you needed tangible skills to live up to that responsibility, e.g., learning how to be a good reader, a good communicator, how to build a coalition, and be a good public speaker. Therefore, when El-Mekki evokes nation-building, it’s a charge for Shoemaker’s students not just to get an education, but to lead and serve in their communities and for Shoemaker’s teachers and leaders to ensure students have what they need to do so.

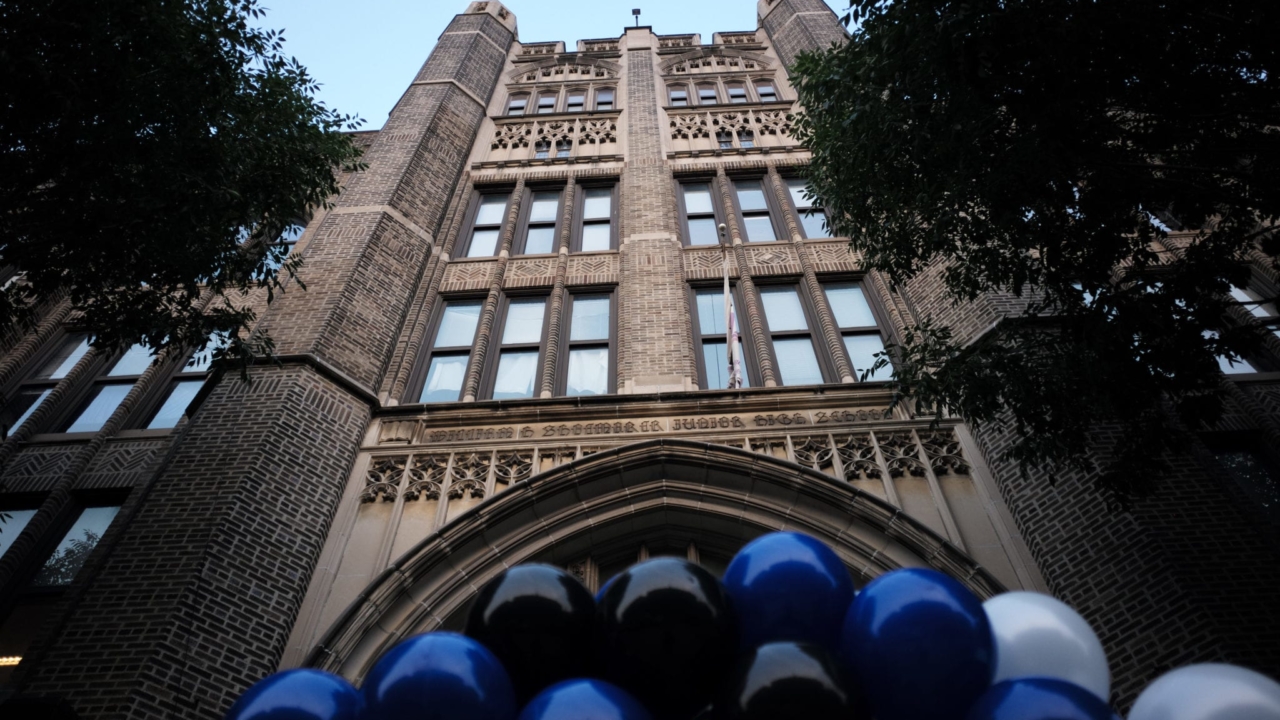

For many of Shoemaker’s students that community is West Philly. Shoemaker is a neighborhood public charter school, so the vast majority of students come from the local community. El-Mekki too grew up nearby. But by the early 2000s, William H. Shoemaker Junior High had become the second most violent middle school in the Philadelphia school district. In 2006, district officials contracted with the Mastery Charter School network to turn the school around. El-Mekki joined the staff a year later.

Under El-Mekki and his team’s leadership, Mastery successfully changed the school’s trajectory, drastically and rapidly increasing test scores. In 2010, the charter network was recognized by President Obama and Oprah Winfrey for their work turning around low-performing schools. More recently, Shoemaker’s outcomes on some academic measures have lagged, as the state adopted new, more rigorous tests to align with Common Core standards. Shoemaker failed to meet academic goals in English language arts and math, for instance. Students overall, however, were successful in reaching growth targets in these areas, meaning there was significant improvement.

Still, that’s not good enough, El-Mekki says. “We’re not going to be satisfied with just growth rates because you can use growth rates for a thousand years and not make the progress that Black kids deserve.” Instead, he’s focused on “shooting for an absolute bar.” And to get there, the staff is going deeper on coaching to ensure consistency and growth, using planning meetings to collaborate and unpack the rigorous content and instructional standards, and analyzing their students’ work to make the connection to what teachers are asking students to do in the classroom and the absolute bar for grade level work.

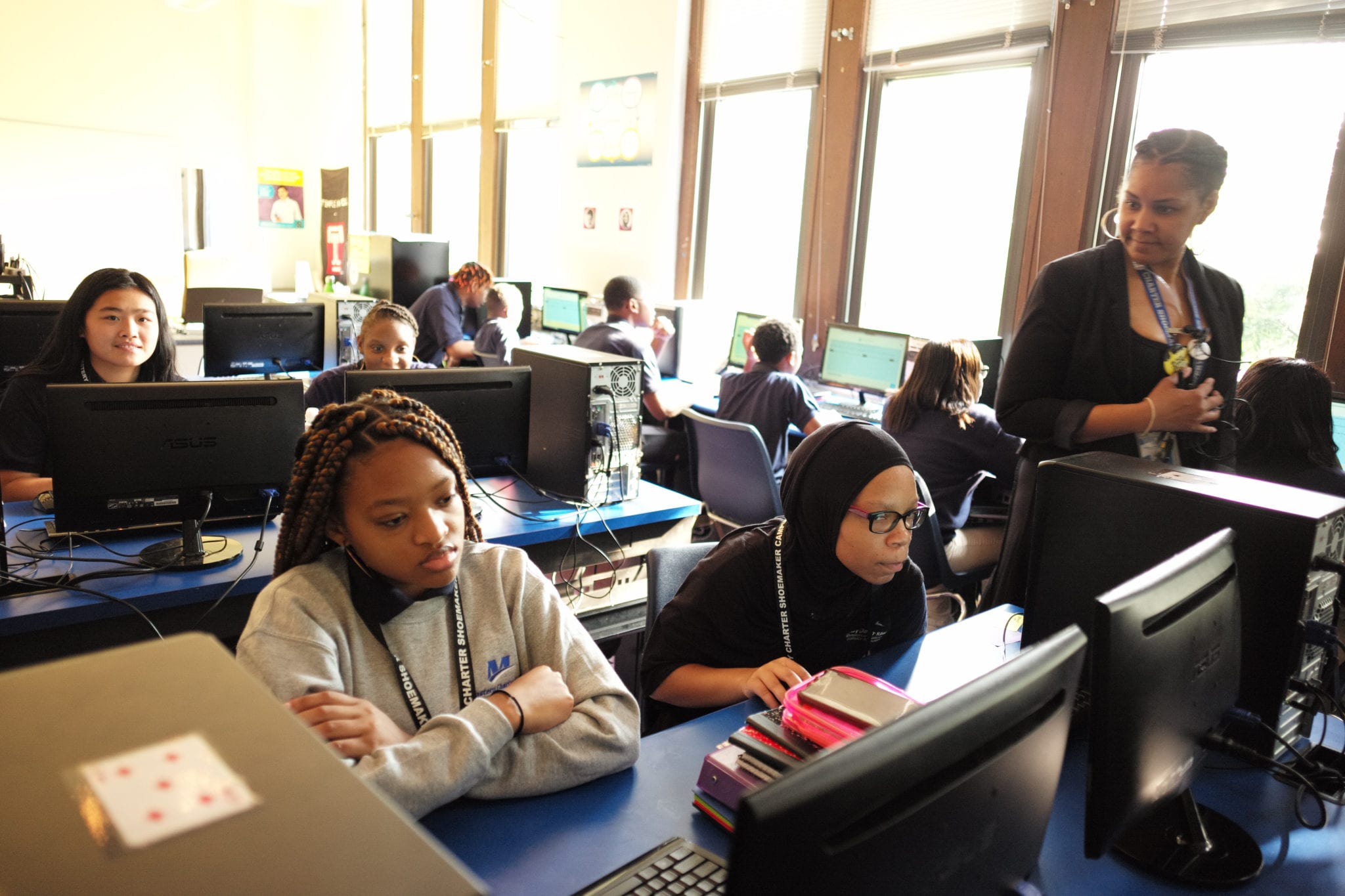

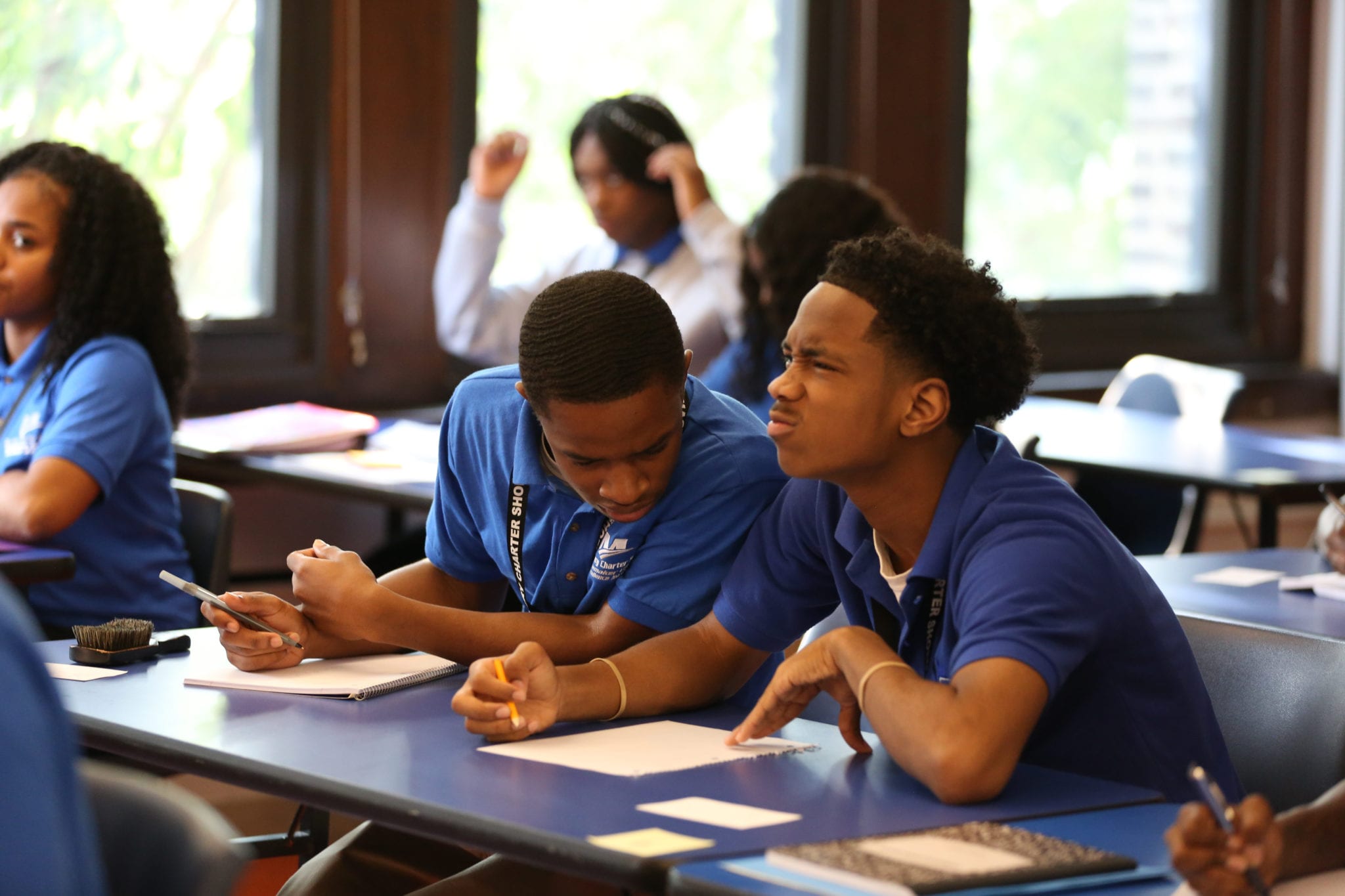

But test scores are just one component of any school’s story. What also matters is the environment in which students are expected to learn. Do students cite positive racial and cultural experiences, healthy relationships, high expectations, and a sincere belief that they can succeed? Shoemaker’s students, more than 95% of whom are Black, say they feel supported, motivated, safe, and culturally affirmed. “It’s just like the sense of community I get when I walk in these doors is just amazing. I feel like I won’t ever get that feeling anywhere else,” said one 10th grader. “It’s a safe house,” said another.

Teachers too cite an environment that’s supportive and welcoming. This is contrary to what many Black teachers, in particular, say about their experiences in schools. “When I come into this building, I think it’s my house. I’m home. I’m taking a trip from home to home,” said one teacher. “The reason I’ve been here so long is because of the family here at Shoemaker,” said another.

That family or extended community is better known as the “ShoeCrew.” “We brag different.” “We graduate twice” (referencing school pride in succeeding beyond high school, whether it’s college, the military or career). And the emphasis on the collective is a reminder that there is no one individual to credit. As in all families, each member contributes. But, teachers and students do point to El-Mekki’s leadership as essential to nurturing a space where Black students and Black educators feel they belong and have the opportunity to thrive.

El-Mekki’s leadership is marked by his own cultural pride, a personal record of activism, and an unapologetic commitment to making sure Black students have the supports and tools to do the nation-building their community requires them to do. As such, he says, “I’m always talking and walking on social justice issues, and I’m going to lead with that. I’m trying to lead with equity and justice in thought and action.”

Bring Back Freedom School

Equity and justice are popular terms among today’s education advocates, and especially among those fighting to overturn systemic inequities and historical disadvantages. But what does it mean to lead with equity and justice? What does it look like in action?

For El-Mekki, it looks a lot like what he remembers from his experience at Nidhamu Sasa, a Pan African school in Philadelphia’s Germantown neighborhood. In the 1960s and ’70s, leaders in the Civil Rights, Black Panther, and Pan African movements founded freedom or liberation schools to counter the reality that the curriculum being taught in majority White educational settings often rendered African American history, literature, and culture invisible. Black teachers taught Black students the importance of centering one’s racial identity, knowing one’s history, being a part of a community, and having a purpose — all with the broader goal of achieving social justice.

“Nidhamu Sasa was an option for families who were really looking to ensure their children’s whole self was honored, respected, celebrated, loved deeply by every adult in the building, from the secretary staff to the custodial to the teachers and the principals. I remember the staff and families coining it as an alternative learning experience,” he says.

El-Mekki admits that how he speaks to students today is influenced by his experience as a child. “Almost every day, I have freedom songs playing in my head when I’m engaging with students.” He remembers this one especially about identity, community, and purpose — key tenets of the freedom or liberation school model:

I went to a meeting last night, and my feeling just wasn’t right.

You know I thought that stuff about Blackness just wasn’t for me.

And when I found out it was for me, I joined in the unity.

And now I’m down for the struggle for liberation.

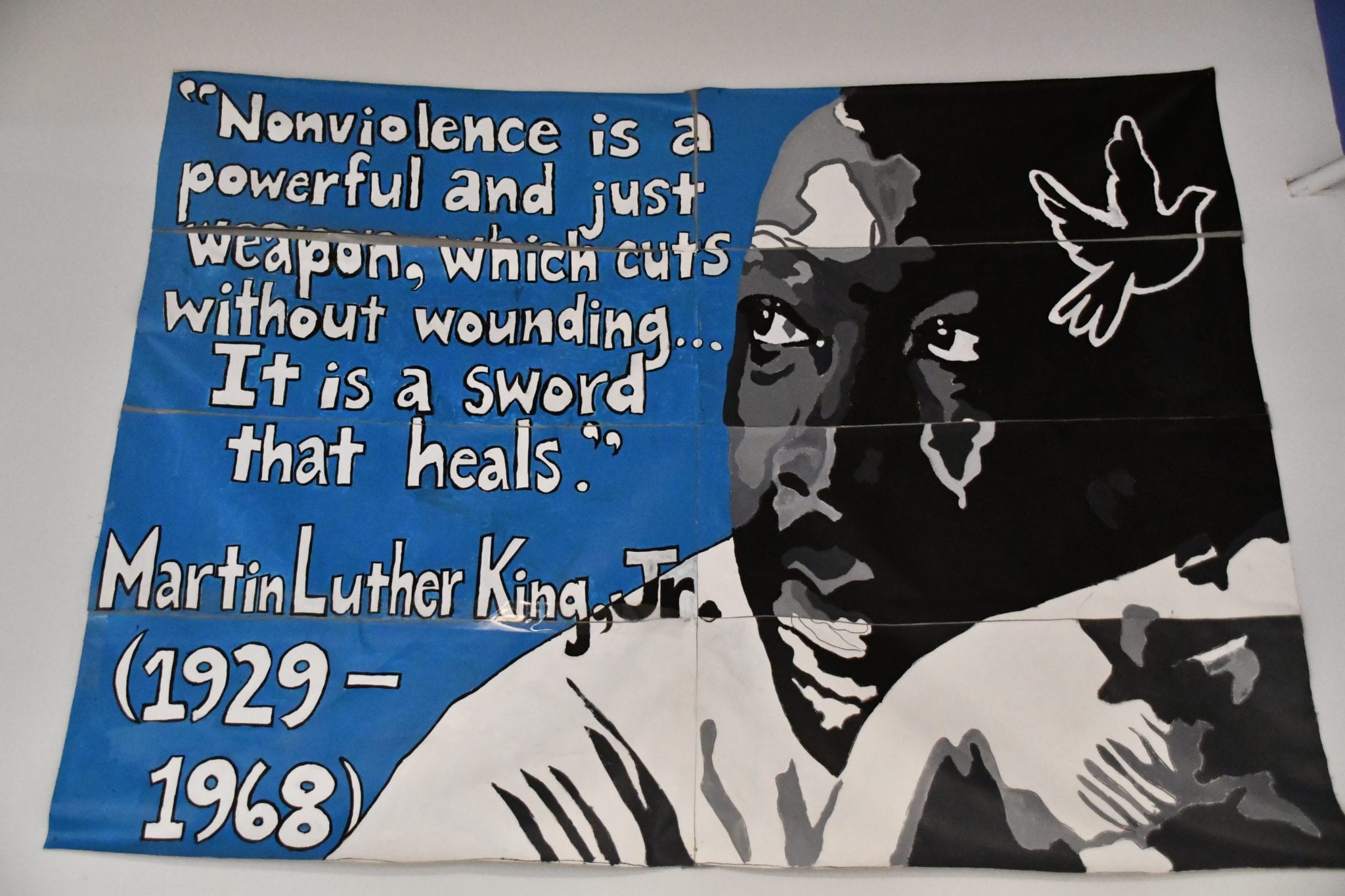

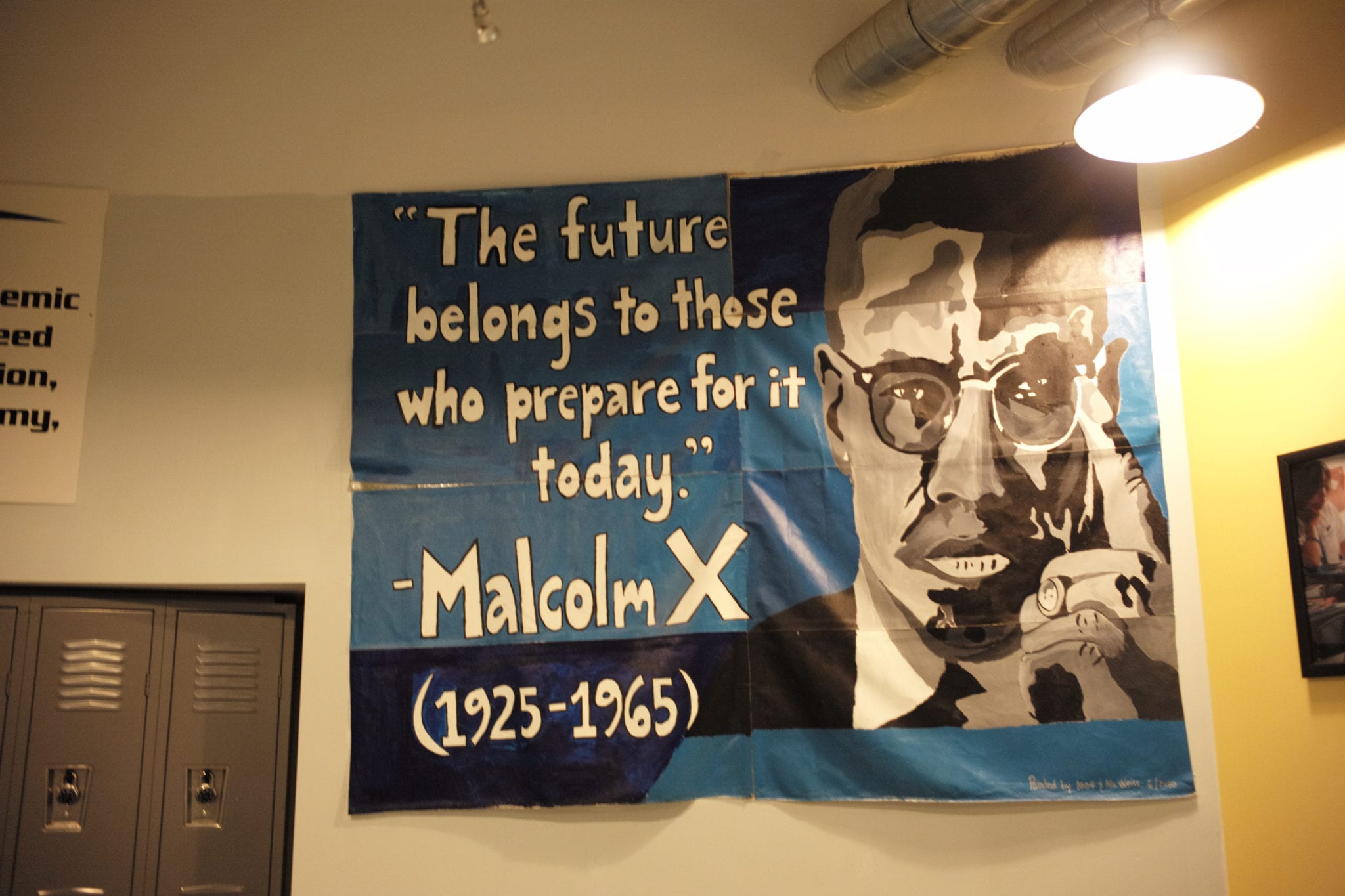

He also remembers songs about historic Black leaders, such as Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and Sojourner Truth. But, as important, students at Nidhamu Sasa learned about and from contemporary activists — those making history at the time. Sonia Sanchez, whose child was one of El-Mekki’s schoolmates, would recite her revolutionary poetry for students. Angela Davis also visited the school and spent time with students. “We were at their feet learning right after math class or right after literature class. … learning from folks who were using activism to try to change society,” El-Mekki says.

At Nidhamu Sasa, the teachers were not just teachers but activists, and they saw themselves as raising activists, says El-Mekki. They looked at the idea of loving Black children as revolutionary — not that they really believed it was revolutionary, he explains, but in contrast to what was happening in the world, it was.

Decades later, Black children still encounter a world where accessing a high-quality education is a revolutionary act, and where the images they see daily and the lessons they are taught about their history and communities are too often more likely to demean than affirm.

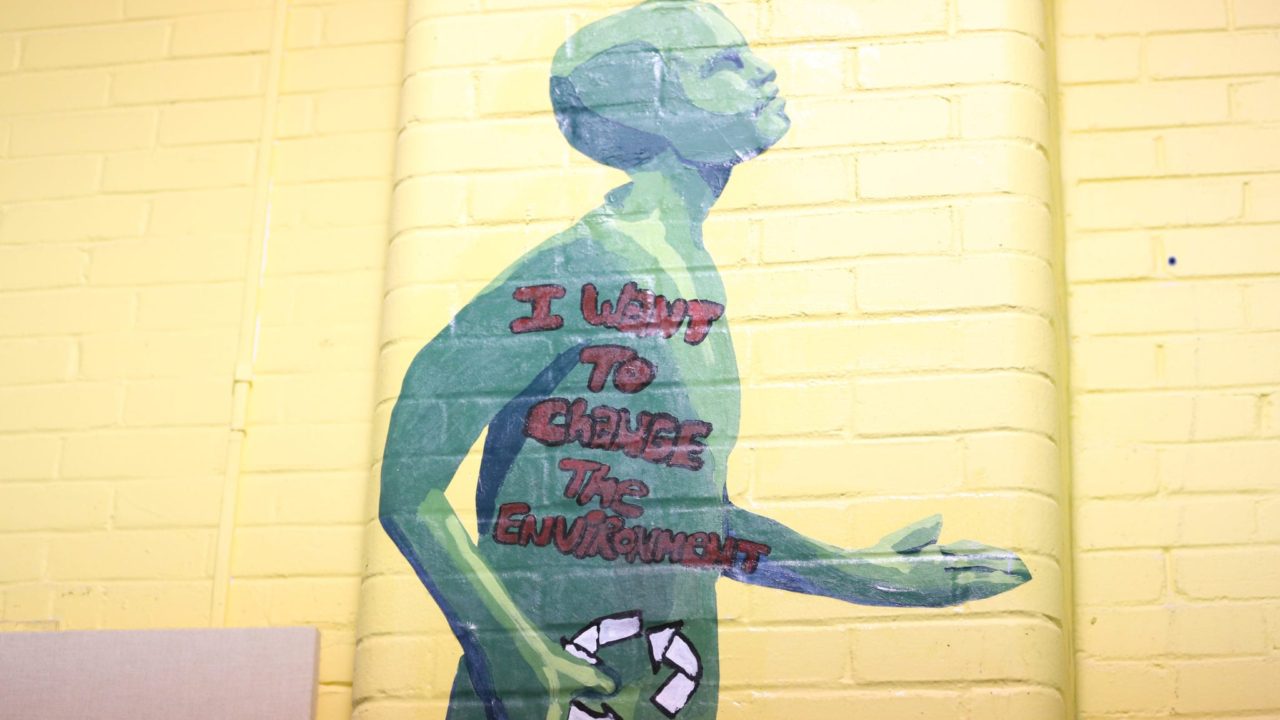

But at Shoemaker, the photographs on the walls are primarily those of Black scholars, activists, and influencers. The books on the shelves are those of Black authors. And the inspirational quotes that line the concrete block walls feature those of Black leaders. Students see mirrors, instead of just windows, says El-Mekki, referring to the idea that Black students rarely see people who look like them in positions of leadership or as examples of intellectual excellence. White students, on the other hand, often only see people who look like them in such roles.

And instead of the message Black students hear so often growing up in impoverished neighborhoods, i.e., to get a degree and get out, at Shoemaker the prevailing message is to “lift as you climb.” It’s another phrase that El-Mekki remembers from his own freedom schooling, and you’ll see it displayed prominently around the halls of Shoemaker — a reminder to students (and staff) of the responsibility to lead and serve their community.

“We’re bringing back freedom school,” El-Mekki says.

Lift As You Climb

Working alongside El-Mekki are other staff members who have either attended schools that were built on the freedom or liberation school model, or have taught in one. They too know the legacy first-hand and work with the entire team to infuse elements of the model into the school’s curriculum, culture, and overall foundation.

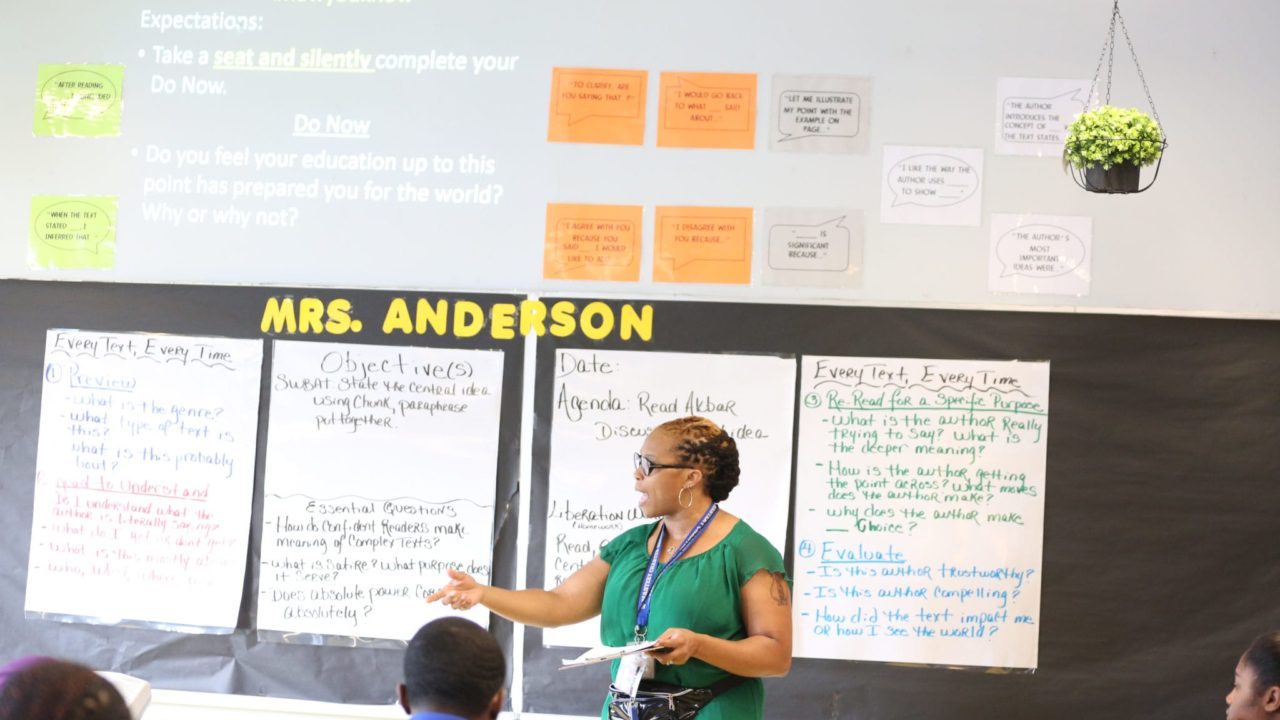

“It all starts with identity,” says literature teacher Njemele Tamala Anderson. Before joining the Shoemaker team, she taught writing at an African-centered charter school and a service-learning focused school based on the freedom school model, both in Philadelphia.

Anderson starts each year having students read sections from noted Black scholar Na’im Akbar’s book, Know Thy Self. Akbar helped pioneer an African-centered approach to psychology. The excerpts provide a foundational framework for her class, linking education to a broader purpose in students’ lives. “You should learn your identity through your education, and your education should also equip you with power to control your resources, so that you can get your basic needs met and then also that you can help meet the needs of the community,” she says.

Upstairs, seventh-grade writing teacher, Ansharaye Hines, (who is Anderson’s daughter) also weaves a lesson of identity, history, purpose, and community. She tells Shoemaker’s newest cohort what to expect: “You will read and write each day. You will use your voices to inspire others.” Writing, she explains, is an extension of ourselves: “We live in connection to a lot of other things. And every time we put a pencil to a paper, we are thinking about those things.”

But writing too serves a greater purpose. Authors influence those who come after them, “affect[ing] and echo[ing] throughout history for the rest of eternity, depending on how long their books last, and their words last,” she says. The assignment this day is for them to reflect on what helped them make it to seventh grade and to write a letter to younger classmates, giving them advice on how to do the same, essentially lifting as they climb.

Shoemaker’s students have internalized the “lift as you climb” motto. Juniors and seniors mention feeling a sense of responsibility and talk of careers in fields where they can serve. Twelfth-grader Armanie, for example, plans to be an early childhood educator focusing on mental health. “If I had the right people at the time being I would be in a better place — not saying I’m not now, but I think my journey would have been a little smoother,” she says.

Aspiring psychiatrist Jaya, also in the 12th grade, shares a similar goal, narrowing her focus on students of color: “I think mental health is really important to serving the youth that need it most, which I think is marginalized youth, especially of color,” she says. “I want to be able to serve youth like I would have liked to be served.”

Tenth-grader Kymarr wants to help eliminate the dearth of Black male educators and become a teacher. He’s following the path of one of his deans, who he says inspired him: “Seeing how much an educator inspired and influenced other kids to do good and be their best selves, I want to do the same thing.”

Social Justice at Its Core

El-Mekki was taught early on that education and racial and social justice cannot be separated. So, it’s natural for him to use that as a guiding principle. But his legacy, as he sees it, is leading a school that does the same, one that focuses on social justice as one of “the main reasons for its existence.” Shoemaker’s staff “tends to it … nurtures it … spends time thinking about it as part of its school improvement plan, not separate from it,” El-Mekki says. “We are always talking about what social justice aspects do students need.”

Today, all students are required to take the Social Justice course in the eighth grade. Gerald Dessus, who joined the staff three years ago, designed the course. It’s one of the reasons he came to Shoemaker. In fact, he had accepted a job at his “dream school,” but, after a conversation with El-Mekki, turned it down.

According to Dessus, El-Mekki came to talk to him and asked him to describe his dream classroom. “I told him what my utopian classroom would look like, would feel like, the autonomy that would be involved, the freedom I would have to use different texts and also still ground the work in literature and in writing. And [El-Mekki] said, ‘Why can’t you do that at Shoemaker?’”

Dessus designed the class to follow Bobbie Harro’s Cycle of Liberation. He describes a process that starts with waking up. In class, he says, they call it “cognitive dissonance,” but students know it as “getting woke.” The first unit is about identity, and on the first day he asks students to jot down definitions of identity, as well as factors that might shape it. “In eighth grade, you’re not going to have the strongest sense of identity, but making sure that they’re aware of different social identity groups, where they fit in, what they’re still trying to figure out about themselves, so when we get into the work of history and racial identity, that they’re coming from a more aware place than just jumping straight into the content,” Dessus says.

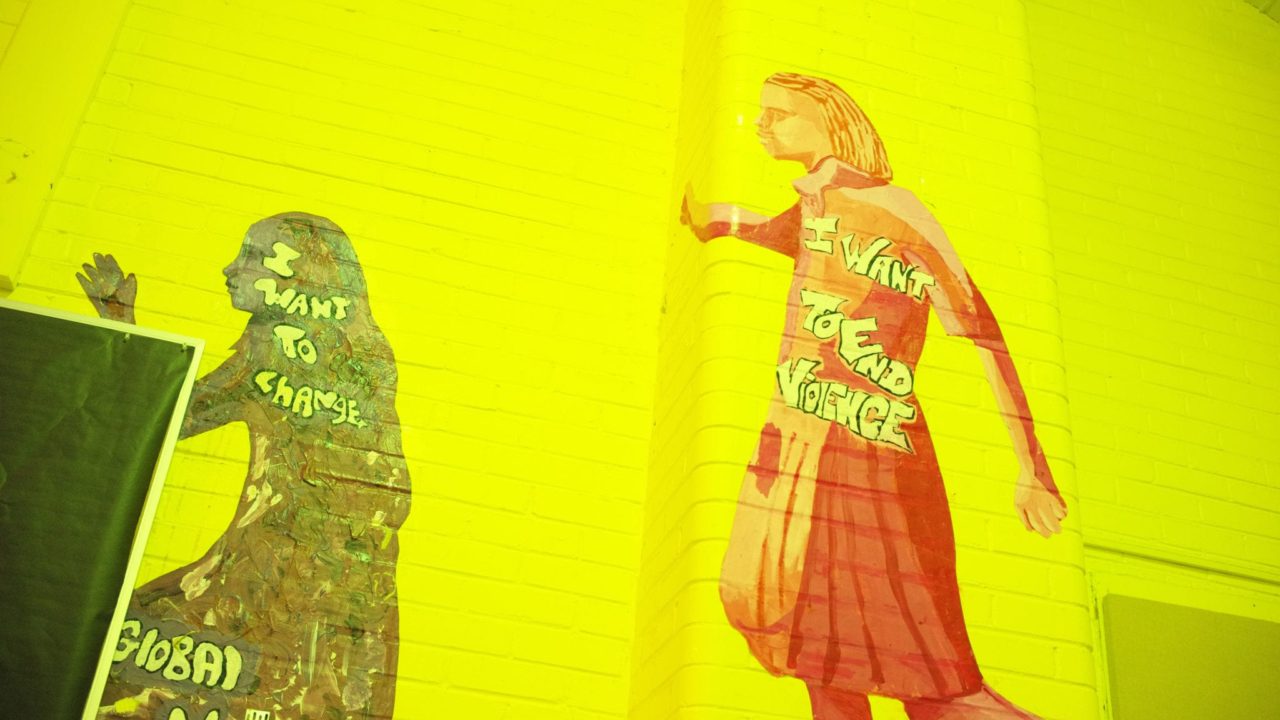

Students go on to study the history of social movements — Civil Rights, Resistance to South African Apartheid, the Black Panther Party, LGBTQ rights. They discuss the wins, the losses, and challenges and use what they learn to help identify what they are passionate about and how they can get others to join their cause.

The course culminates in a real-life exercise in activism, coalition-building, and making change. Each student identifies a problem they want to address, interviews at least 25 stakeholders and others directly affected by the issue, and teams up with other students with similar interests to design an activity that will involve and influence the community. Recent projects range from teaching younger classmates about the impact of colorism to hosting a school visit and conversation with local officers to improve school, community, and police relations.

Focusing on social justice or just racial identity makes an immediate connection for many students, says Dessus. “It’s not just about learning about the Civil Rights Movement or learning about the Black Panther Party but also like naming the struggles, naming the courage that it took … to defy a social system by yourself, and deal with the backlash, and feel like you lost all of your friends … and still stand firm like ‘I made the right decision.’ To me, that motivates our students … to speak up and do the right thing.”

And it’s not just eighth-graders who get the connection between social justice, racial identity, and their daily lives. It’s visible to anyone who walks through Shoemaker’s doors. Just steps away from the main entrance, a collage of recent victims of police brutality and gun violence looms. Some of the names are well known, such as Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown. Some of them are not. But all are shrouded in red, black, and green construction paper lined with a kente border, with #SayTheirNames! in bold letters.

Even the youngest students at Shoemaker are encouraged to contemplate their role in the face of racial injustice. After a trip to see The Hate U Give, the film adaptation of the best-selling young adult novel about police brutality, seventh-graders easily connected the movie to real life. “This is actually going on,” says Christopher. “I’ve seen it on the news and stuff. How people are protesting and the cops just abusing their power. This is real. This actually hits you really hard, like wow.”

And they considered their role as young activists, putting themselves in the scene: “The policeman don’t get consequences. They don’t get nothing. But when we stand up for our rights, then we get bombs thrown at us, get shot, get beat. I don’t think it’s right,” says Tyjai.

In all, the movie made them feel sad, and then upset and angry, they said. But they also felt empowered. “I feel like it was to tell us to never give up and stand up for our rights because the girl who really saved everyone was Black. She was the one who stood up. She was the only girl. She was smaller than everybody else, and she was the only one that stands up,” says Oriana.

“We See This School as a Community”

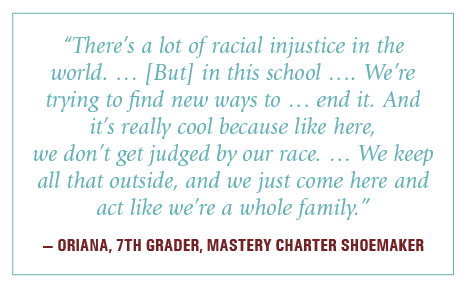

All of this gives Shoemaker’s students the chance to have hard conversations about race and racism, something many adults even have a hard time doing. But what bolsters students, they say, is the supportive school environment.

“There’s a lot of racial injustice in the world,” says seventh-grader Oriana, but “in this school …. We’re trying to find new ways to … end it. And it’s really cool because like here, we don’t get judged by our race. … We keep all that outside, and we just come here and act like we’re a whole family.”

A dynamic exists at Shoemaker where personal relationships are a source for the teaching and learning. “There’s a lot of love, a lot of relationship building, and you can see that in student interactions, you can see that in student and teacher interactions. There’s like a genuine investment in trying to understand where each person is coming from, their experiences. That’s at the forefront of all of our interactions,” says Dessus.

“If you see that your destinies are linked, then you’re going to do whatever you can to make that child successful, not just to pass a test, but in life,” says Anderson.

As a result, lines between school, family, and community are blurred. “We see this school as a community, not just peers and teachers teaching us what we’re going to need when we grow up,” says seventh-grader Tyjai. “We see this school as a community because whenever we need them, they’re there.”

And the support, students say, is not just limited to coming from one or two individual teachers or just from El-Mekki, for that matter. As 12th-grader Armanie explains: “We all come from different walks of life. We may have the same skin color but we have different paths where we’re going. But when we come here, we have the same goals, to do better and be better,” she says. “The deans, the teachers, and the administrators, they make sure we get to where we’re going. Once you come here, you feel that loving vibe.”

Teaching Across Racial Lines

El-Mekki, Anderson, and Dessus are Black and grew up in Philadelphia. El-Mekki grew up just a few blocks from Shoemaker and, until last year, still lived nearby. Anderson also lives just a few blocks over, citing the location as one of the reasons she chose to teach there. They know the neighborhood and the families within, and are themselves, very much a part of it.

But many of Shoemaker’s educators do not fit this profile. (Currently, 40% of teachers are Black, and 50% of overall staff members are Black.) And yet, the school is still able to be a place where Black and Brown students say they feel supported, motivated, confident, culturally affirmed and safe. This means that the teachers who don’t share racial or cultural experiences with the students must still be able to be accountable for carrying out the freedom school legacy of building confident Black students who are empowered to influence change. They too must know their racial identity, value the surrounding community, understand how history influences today’s reality, believe in social justice, and champion an alternative narrative to that which Black and Brown students hear so often outside the school.

Teaching across racial lines and building relationships with students across cultural lines requires self-reflection and self-work, says 11th-grade teacher Ellen Speake, who is White. It’s something that she constantly thinks about, and still doesn’t think about enough, she says. In the classroom, for instance, she has to ask herself, “Would I expect the same of these kids if they were White?”

But one of the reasons why Speake has stayed with the school so long is the value put on building cultural competency within the staff. Art teacher Jessica Oxenberg, who is also White, agrees. She just relocated, and one of the things that brought her to the school was the intentional professional development around building relationships with students across cultural lines. “I’ve been at a lot of schools that talk about it, but don’t have a plan in place,” she says.

Throughout the year, Shoemaker staff hold professional learning communities, or PLCs, where teachers are encouraged to talk openly and candidly about their own biases related to race, class, and privilege. They talk about implicit bias, micro-aggressions, intersectionality, etc. Notably, the sessions are led by teachers and not by an outside facilitator or even by El-Mekki. Although, teachers do credit El-Mekki for empowering them to lead the discussions and for setting an example with his own willingness to talk openly about race.

And just like students, teachers say the supportive environment at Shoemaker creates a safe place for them to have hard conversations. “To be in a space that values [cultural competency professional development], to be among people that also value it, people who can push me, people that I can go to and feel safe going to in moments of vulnerability, knowing that I’ve made a mistake … that was really important to me,” says Speake.

As difficult as such conversations are, prospective teachers must be willing to have them, says Speake. “Their willingness to have those conversations says a lot about how much they value that.” El-Mekki has written about the interview questions that he and his leadership team ask to find the best teachers for Black students – those who (regardless of race) are aligned with Shoemaker’s mission. Questions range from why they want to teach in a Black neighborhood to do they know their own implicit biases to how they feel about being led by a Black principal.

Why Black Teachers Matter

Shoemaker students, however, still crave more Black educators. The Black teachers and administrators at the school have had such an impact, they say, that just having a handful on staff is not enough. They cite a “deep connection,” the ability to relate to them in “deep ways that you don’t even know about.” They discuss the importance of having someone they can go to who they feel will understand them. And students who “might not be on the right path” can see someone like them at the front of the classroom and say, “Oh, I can be like them, and I’m still being myself.”

Students say they appreciate even small gestures of cultural affirmation, such as the way one teacher addresses students in her class: “Oh, the brother in the back has a question,” or “Oh, sister right here in the front has a question.” And how she uses shared cultural experiences to create a welcoming classroom: “One time she was playing Lauryn Hill, and another time she was playing Drake. One time she was playing Fela Kuti.” They value her displays of cultural history, wearing African fabrics and other such attire. One student described her as an “inspiration to Black people everywhere.”

It’s easy to underestimate what it means for some Black students to enter an educational setting and be welcomed, accepted, understood, and affirmed, which eliminates their fears and doubts and how all of it influences their ability to learn something new, grasp difficult concepts, think critically, i.e., perform academically.

“The reassurance our teachers gives us means so much to me personally,” says 10th-grader Bryce. “Some days, coming from where I come from … I’m going to school whether I’m in good spirits mentally or not, and the fact that my teachers can so easily sense that without me having to say it. It makes me feel like I’m at my second home. Like I’m at my grandfather or uncle’s house watching the game, just doing assignments.”

Shoemaker’s Black teachers and leaders then are not only educators, but role-models — someone for students to see themselves in, to look up to, and to emulate. And like many Black educators across the country, their ability to connect with Black students through shared cultural experiences helps students feel connected to their school and their education more broadly. Black students who have at least one Black teacher in elementary school are less likely to drop out of high school and more likely to enroll in college. And yet, Black teachers make up only 7% of the nation’s teaching workforce.

A New Revolution

El-Mekki’s activist parents and teachers groomed him to be a revolutionary. But he struggled to know what that looked like for him, reaching adulthood years after the Civil Rights and Black Panther Party movements peaked. Yet, after being shot on the football field by a young Black man and more than 12 surgeries to save his leg, he found the answer: “My revolution was to be a Black man by a blackboard in Southwest Philadelphia in that same part of town where that young man had shot me,” he reveals on the Moth Podcast.

For the past 26 years, he has acted just steps away from blackboards — as a teacher and administrator at Turner and Shaw middle schools in Southwest Philadelphia, and then principal at Shoemaker. But the urgent need to have more Black educators in the classrooms in Shoemaker, in the city of Philadelphia, and across the country is summoning El-Mekki to a new revolution.

In 2014, he founded The Fellowship: Black Male Educators for Social Justice, an organization dedicated to recruiting, retaining, and developing Black male teachers. It started as a small support group of fewer than 20 Black men. They met over dinner to share stories, help each other solve problems, and to build a community. The group has grown exponentially over the years. It now hosts a number of meetings throughout the year for Black educators (and those who supervise or support them) to learn from each other. The hallmark event is the annual convening, which last year drew over 1,000 participants to Philadelphia. The Fellowship’s big goal is to triple the number of Black male educators in Philadelphia by 2025.

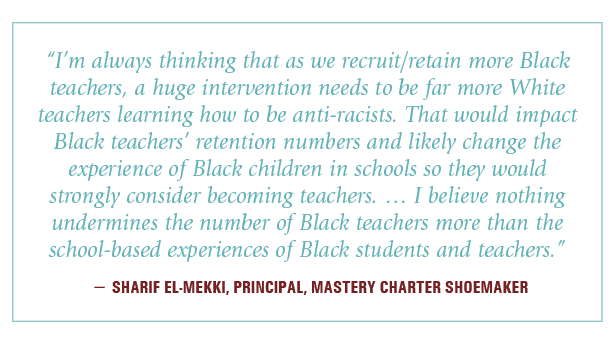

Soon, however, El-Mekki will be leaving the day-to-day of Shoemaker to launch a new initiative under the Fellowship’s larger umbrella with a heightened focus on professional development for Black teachers and cultural responsiveness for other educators, as well as the pipeline to the classroom and policies that can support or thwart new and aspiring Black teachers. Instead of offering one-off or periodic PD opportunities, the Center for Black Educator Development will provide ongoing and direct mentoring support and coaching. Considering that the vast majority of educators are White (e.g., 96% of Pennsylvania’s teachers), making sure all educators are culturally competent and responsive is an essential piece, El-Mekki says. “I’m always thinking that as we recruit/retain more Black teachers, a huge intervention needs to be far more White teachers learning how to be anti-racists. That would impact Black teachers’ retention numbers and likely change the experience of Black children in schools so they would strongly consider becoming teachers. … I believe nothing undermines the number of Black teachers more than the school-based experiences of Black students and teachers.”

The center will also carry forth the freedom or liberation school legacy, by hosting a year-round Freedom School. Philadelphia already has several sites where college students/servant leaders spend six to eight weeks teaching and mentoring elementary school students/scholars. One priority for the center’s Freedom School will be to incorporate research-based curricula. Another priority will be to make sure high school students teaching alongside college students are being actively recruited to consider becoming teachers, El-Mekki says. The goal is to expose as many young people as possible to the teaching profession to help fuel a pipeline of Black educators.

Increasing his efforts to get more Black educators in the profession and to provide them with the support they need to thrive is El-Mekki’s way of answering his own call to get “back to nation-building.” His responsibility is to more than just the students who come through Shoemaker’s doors, but to the 200,000-plus students in Philadelphia’s school district, the eighth largest in the nation.

It’s also his way of helping to build a movement toward educational justice, part of which is ensuring that the adults who work with students hold themselves accountable for what students are able to do, he says. “If we have that, and if we look at every child in our schools as our own children, and that we bring the love and commitment to outcomes, then we will radically transform educational spaces and schools in our communities.”