Appreciating Unexpected Teachers in America’s Unsung Classrooms

Many teachers talk of being “called” to the classroom, drawn by a force that latched itself to their very souls early on in school and held fast, as if no…

Many teachers talk of being “called” to the classroom, drawn by a force that latched itself to their very souls early on in school and held fast, as if no other destiny were possible. Others arrive by happy accident.

Mr. Steve counts himself among the latter.

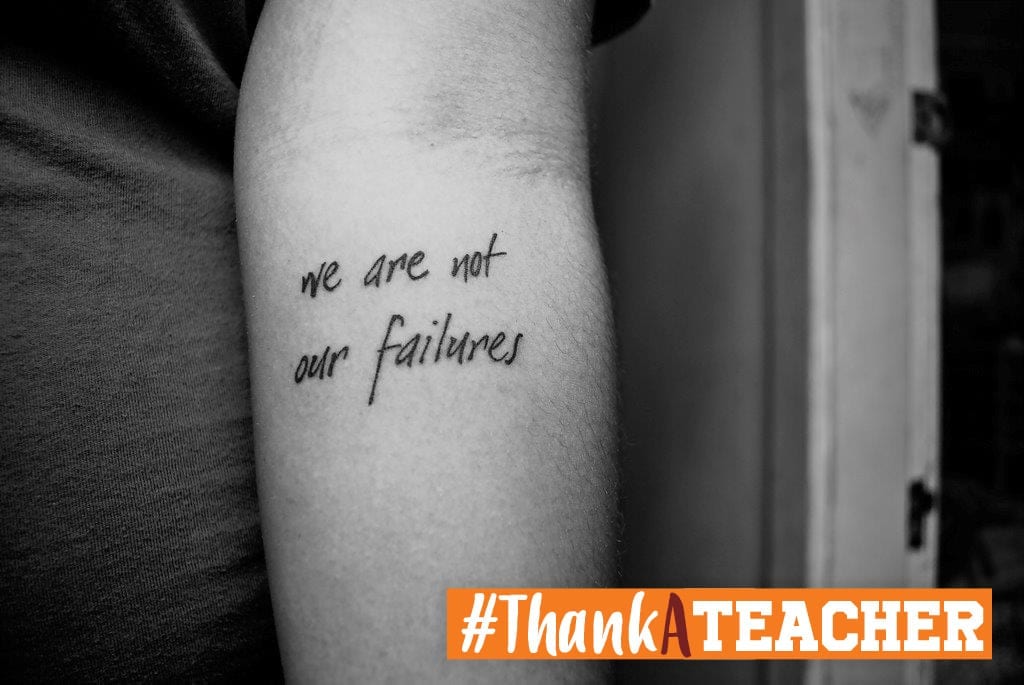

The burly White guy with a shaved head, an impressive sleeve of tattoos, and an easy smile never loved school. He never even liked it. A self-described “hard-headed kid,” he always had to learn for himself — often the hard way. He bumped against the traditional, rigid structure and rules of school, staying in only so he could continue to play football. And when he left, he never looked back.

Or at least never thought he would.

Until, in an ironic twist of fate, he found himself taking a teaching job at a juvenile detention facility.

In that facility, the reluctant-student-turned-teacher came face-to-face with young potential left to atrophy in cell blocks. He encountered time and time again the too-familiar stories of struggle and neglect and interventions that came too late — or never came at all. It was there that he fell fast in love with his students — and with teaching.

And it was where his own experiences as a reluctant student blossomed into the keen instincts of a great teacher.

Where some teachers might have seen defiance, he saw fierce independence. Where some might have seen irreparable damage, he saw the marks of resilience. And where some might have seen insurmountable deficits, he saw treasure troves of raw knowledge and intellect ripe with yet-to-be-made connections to classroom learning.

And that’s how he taught, and does to this day — with a deep respect for and belief in the capacity and worth of his students. And with the notion that it was not the kids, but rather the system, that needed to change.

“I think there’s just too many rules and too much structure,” he leveled. “I mean, it’s needed in some regards. You can’t have an unstructured environment, because some people take advantage of that, right? But once they get to a certain age, I see them not taking advantage of that. And they actually rise to the occasion and do what they’re supposed to do. I trust them to do what they need to do to be successful.” This is particularly important, he says, for the young people he serves who are often, by necessity and experience, beyond their years in maturity and independence.

And, in Mr. Steve’s classroom, that trust extends to the very way he engages students in learning and gives them ownership. “At the end of the day, I can sit there and hold their hand and drag them through and give them answers. But I can’t stand that. So I use a Socratic means. I ask a whole lot of questions for them to answer and think about.

“I’m teaching them that this is their education — I’m just a facilitator. This is not my class; this is our class. I try to give them the reins to take control of their own education. And they really engage in that.”

Mr. Steve is still in the classroom, now serving as a GED teacher in an alternative school for previously school-disconnected, often system-involved students.

“I wasn’t ever looking at myself as a savior,” he shared, “I was looking at myself as somebody who could maybe be instrumental in understanding — that the school mold doesn’t always fit. I wanted to help change the mold. And try to give these students a different route than maybe the one they’ve been exposed to.”

Some teachers are called to the classroom, their love of learning and school infectious. But for students who have struggled, unexpected teachers like Mr. Steve may be just what they — and our schools — need more of.