Understanding and fixing inequities in student success requires better data

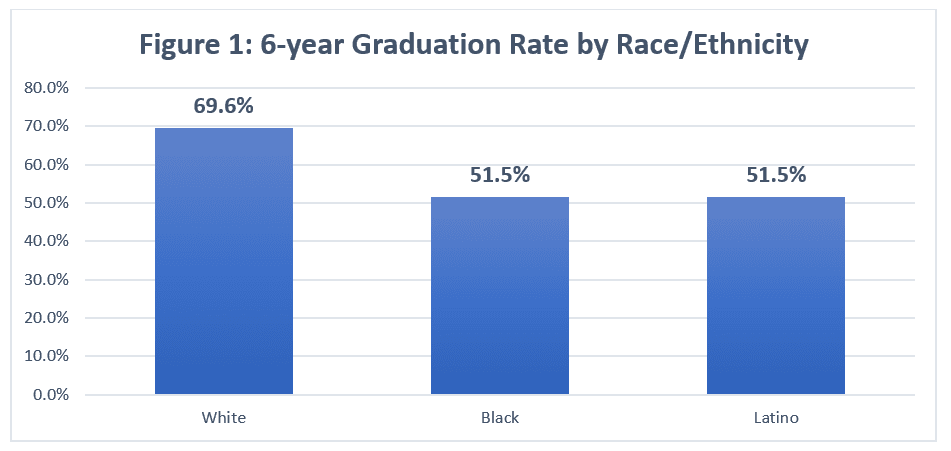

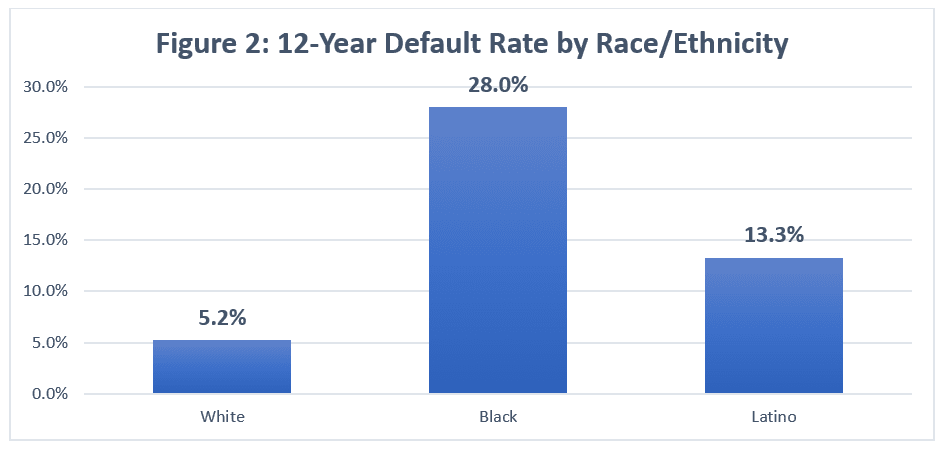

Our analysis shows that the gap in graduation rates doesn’t fully illuminate the racial differences in student success. A successful college experience cannot just be gauged by what happens on graduation day. What happens after a student leaves and enters the workforce must be considered, too.

We need better data on this. Each year, the Department of Education (ED) collects and reports some data from its National Student Loan Data System (NSLDS) (i.e., three-year cohort default rates). But, currently, we have no way of consistently knowing how federal loan default rates differ by race and ethnicity at individual colleges and universities. This is a huge problem. Although we used data from the Beginning Postsecondary Student (BPS) Longitudinal Study to capture default rates by race and ethnicity, BPS only tracks a cohort every eight years, making it difficult to get timely data on how and to what extent loan default rates differ by race. The ED must create a secure federal student-level system of de-identified data that connects student characteristics — such as income, parental education, and race — with financial aid, enrollment, and completion records. The good news is, the College Transparency Act, if enacted, would do just that, while helping to ease a reporting burden that is already overwhelming many of our postsecondary institutions.

The bad news is, better data won’t magically lower loan default rates, but in the hands of students and parents, policymakers, and institutional leaders, it could help ensure that the federal government and taxpayers — not to mention, students themselves — get a better return on their $60-billion-a-year-investment in undergraduate loans. At the very least, it would give students and parents a more accurate and inclusive picture of which colleges actually prepare students for success, thereby helping students to avoid those institutions that produce default-prone graduates. Policymakers could use this data to develop stronger consumer protection policies that incentivize institutions whose graduates don’t do well in the labor market to improve. Better data could also help institutional leaders make better decisions about how they allocate student support resources. For the time being, graduation rates will have to do, but acquiring more and better data must be a priority as Congress looks to reauthorize the Higher Education Act.

Quite frankly, we can and should do better. Our students deserve it.

*Editor’s note: The Education Trust follows new guidelines of The Associated Press on using singular verbs and pronouns with the word data.