Social, Emotional, and Academic Development (SEAD) Assessments: A Framework for State and District Leaders

Schools should use assessments to measure whether they are meeting students’ social and emotional development needs

EdTrust in Texas advocates for an equitable education for Black and Latino students and students from low-income backgrounds across the state. We believe in centering the voices of Texas students and families as we work alongside them for the better future they deserve.

Our mission is to close the gaps in opportunity and achievement that disproportionately impact students who are the most underserved, with a particular focus on Black and Latino/a students and students from low-income backgrounds.

EdTrust–New York is a statewide education policy and advocacy organization focused first and foremost on doing right by New York’s children. Although many organizations speak up for the adults employed by schools and colleges, we advocate for students, especially those whose needs and potential are often overlooked.

EdTrust-Tennessee advocates for equitable education for historically-underserved students across the state. We believe in centering the voices of Tennessee students and families as we work alongside them for the future they deserve.

EdTrust–West is committed to dismantling the racial and economic barriers embedded in the California education system. Through our research and advocacy, EdTrust-West engages diverse communities dedicated to education equity and justice and increases political and public will to build an education system where students of color and multilingual learners, especially those experiencing poverty, will thrive.

The Education Trust in Louisiana works to promote educational equity for historically underserved students in the Louisiana’s schools. We work alongside students, families, and communities to build urgency and collective will for educational equity and justice.

EdTrust in Texas advocates for an equitable education for historically-underserved students across the state. We believe in centering the voices of Texas students and families as we work alongside them for the better future they deserve.

The Education Trust team in Massachusetts convenes and supports the Massachusetts Education Equity Partnership (MEEP), a collective effort of more than 20 social justice, civil rights and education organizations from across the Commonwealth working together to promote educational equity for historically underserved students in our state’s schools.

Schools should use assessments to measure whether they are meeting students’ social and emotional development needs

Students’ social and emotional well-being is a prerequisite for learning. In the 2023-24 school year, 83 percent of school principals reported that their schools used and social and emotional learning curriculum.[1] However, supporting the social, emotional, and academic development (SEAD) of students must include a broader approach. As a previous EdTrust report, “Social, Emotional, and Academic Development Through an Equity Lens,” noted, these efforts must include efforts to re-shape systems to create inclusive and holistically supportive learning environments.[2]

The pandemic only highlighted the need to support students’ SEAD with an integrated approach. As students’ lives were upended by loss, social isolation, and other challenges and stressors during the COVID-19 pandemic, they were understandably changed when they returned to in-person learning. Students were no longer accustomed to the rigid expectations of the classroom, such as remaining seated for long stretches, and many needed support in re-building relationships with adults and peers. Reports of “student misbehavior” rose across the country — a symptom of the unmet social, emotional, and mental health needs of students, the unaddressed biases of adults working with these students, and lack of evidence-based training and support for educators on how to support students holistically.[3] Four years on, the pandemic’s effects still linger.

To address student well-being in schools, leaders need data to understand what issues students are facing and what priorities they need to address. Just as schools use academic assessments to evaluate whether academic instruction in schools is effective, schools should also use assessments to measure whether they are meeting students’ social and emotional development needs.[4] There are a variety of assessments focused on this area, from those focusing on students’ social and emotional learning (SEL) skills (e.g., relationship skills and self-management) to those measuring aspects of school climate (e.g. students’ sense of belonging and safety at school).

For comprehensive guidance on creating positive and inviting school climates and providing necessary student supports and interventions, district leaders can use tools — especially the guidebooks — created by the Alliance for Resource Equity (a partnership between EdTrust and Education Resource Strategies) to identify and implement improvements to students’ experiences. SEAD assessments are one part of the data ecosystem that district leaders need to use to create school environments that meet students’ social, emotional, and academic needs.

Many SEAD assessments have been developed within the past 20 years, and there has been less focus on the quality of SEAD assessments than on the quality of academic assessments. While state academic assessments are subject to high standards of technical quality and significant scrutiny from experts in assessment and psychometrics, SEAD assessments are not typically subject to the same level of scrutiny. In fact, many developers do not provide basic information about the validity and reliability of these assessments.[5] Education leaders should ensure they are selecting high-quality, research-based, and equity-focused SEAD assessments, as misguided approaches can harm vulnerable students.

The first part of this report offers a framework of 12 questions that education leaders at the state, district, and school levels can use to review SEAD assessments and select valid surveys that meet their specific needs. EdTrust developed this framework using an equity lens to ensure that leaders have tools to select assessments that truly capture the experiences, strengths, and needs of all students. The framework focuses on four key aspects of SEAD assessments:

EdTrust tested and refined this framework by evaluating 11 commonly used assessments that measure aspects of SEAD (see Table 1). While there are many other SEAD assessments available, EdTrust’s analysis of these 11 assessments shows how leaders can use our framework to review other SEAD assessments. EdTrust reviewed these assessments in late 2023 and the ratings included in this report may not yet reflect changes that developers continuously make to improve their assessments. Importantly, evaluating SEAD assessments should be done with the delicate balance of recognizing that one assessment will not meet all needs while still considering the assessment fatigue that can easily overwhelm students and staff. For these reasons, we encourage readers to focus more on the guidance in this report of what to look for in a SEAD assessment, rather than just the ratings of the sample of assessments included in this report. In the second part of this report, we offer recommendations for consideration in developing a system of assessments and using the data from these assessments for continuous improvement at the end of this report. Finally, further details on the findings from our SEAD assessment review and the full evaluation tool can be found in the appendices.

EdTrust selected the 11 assessments displayed in Table 1 below because they represent a broad range of assessment options, including those that are widely used based on our own experiences in this field, those that are commonly cited in SEAD literature, those that attempt to center equity, those that are open access, and those that were recommended for inclusion by our advisory group.[6]

We reviewed materials on the assessment websites, including the assessment items, research reports such as validation studies, implementation guidance, and other available materials. In cases where some information was not publicly accessible, we reached out to the assessment developer. We had conversations with the developers of the Devereux Student Strengths Assessment (DESSA), the New Jersey School Climate Improvement (NJ SCI) Survey, Catalyze and Elevate from the Project for Education Research That Scales (PERTS), Cultivate from the University of Chicago, and 5Essentials; in addition, the developers of DESSA shared materials with us, including research reports and assessment items. Two of the assessments — the Inventory of School Climate and School Climate for Diversity — were published in academic articles and do not have websites with further guidance.

Each assessment was reviewed for whether it met our criteria for each of the 12 questions in the framework. Assessments were categorized as “meets all criteria,” “meets some criteria,” or “does not meet criteria” for each question. At the end of each section of this framework, there is a summary of ratings for each assessment; full details of ratings are presented in the Appendix.

Most assessments related to SEAD focus on one of three categories: students’ social-emotional skills and competencies, school climate, or learning conditions. Some assessments have a narrow focus within one of these categories, such as School Climate for Diversity, which focuses specifically on school racial climate. Different assessments are also designed to be used at specific organizational levels and provide varying levels of data, from student level to district level. Some assessments provide multiple levels of data; for example, an assessment may focus on the classroom level, but data may also be aggregated and analyzed at the school or district level. Table 1 below shows the assessments that EdTrust reviewed, their area of focus, and the organizational level at which they are mainly used. It also notes how easily accessible each assessment is and whether there are accompanying resources.

Our analysis of existing SEAD assessments found that no single assessment covers all aspects of SEAD, so when selecting an assessment, it is important to consider what an assessment is measuring, what organizational level (district, school, classroom, etc.) it is designed for, and whose perspective it is designed to elicit. To see the big picture, state and district leaders must create a comprehensive system of SEAD assessments that, when used together with other existing data, gives practitioners and policymakers the information they need to make continuous improvements, while also not overwhelming students and staff with assessment fatigue.

Assessments rooted in equity lead with an asset-based framing that seeks out students’ strengths first, while also acknowledging that many students face systemic barriers and have experiences that affect their social, emotional, and academic development. Using assessments that focus on students’ assets and recognize their contexts and cultural identity drives SEAD efforts that support all students and ensures that they feel safe and accepted at school. Without this framing, SEAD assessments run the risk of reinforcing stereotypes and biases and could lead to approaches that do more harm than good.[8],[9] Leaders can use the following three questions to assess whether an assessment is rooted in equity.

Assessments rooted in equity lead with an asset-based framing that seeks out students’ strengths first, while also acknowledging that many students face systemic barriers and have experiences that affect their social, emotional, and academic development. Using assessments that focus on students’ assets and recognize their contexts and cultural identity drives SEAD efforts that support all students and ensures that they feel safe and accepted at school. Without this framing, SEAD assessments run the risk of reinforcing stereotypes and biases and could lead to approaches that do more harm than good.[8],[9] Leaders can use the following three questions to assess whether an assessment is rooted in equity.

1. Do the developers center equity in the purpose and intended use of the assessment?

What to Look For:

The developers use an equity lens (e.g., anti-racist or liberatory) to describe the purpose and intended use of the assessment.

Developers explicitly recognize systemic inequities facing traditionally under-represented student groups and indicate how the assessment can be used to address them.

Developers identify the purpose of the assessment using an asset-based lens — e.g., they highlight the assets of traditionally under-represented students, rather than searching for deficits.

Developers provide clear examples of how responses to assessment results, such as policy and practice changes, can address disparities.

Assessments that Are Strong in This Area:

Catalyze

School Climate for Diversity

SAESECI

Cultivate

2. Do all or most items in the assessment use a strength-based lens?

What To Look For:

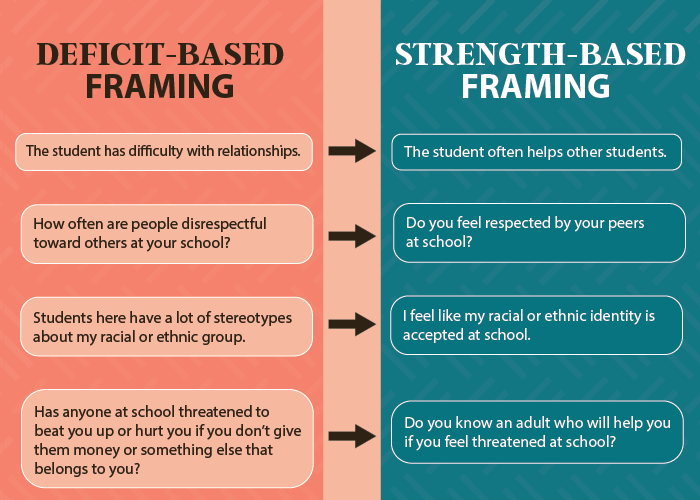

Items center on what students are doing well, even in the face of struggles — e.g., “How often does the student reach out to help other students?” vs. “Does the child have difficulty with relationships?”

Some assessments mostly have items that focus on students’ experiences, rather than their competencies and actions. These items should be framed in a way that highlights the student’s experience, rather than making assumptions about negative behaviors of other students — e.g., “I feel that I am treated differently by other students at school because of my race,” rather than “Other students have a lot of stereotypes about my race.”

Assessments that Are Strong in This Area:

SAESECI

5Essentials

Catalyze

Cultivate

DESSA

Elevate

3. Does the assessment include an array of items to capture the full picture of students’ experiences?

What To Look For:

Assessment items focus on students’ experiences and not primarily on their competencies and skills.

The assessment includes items on students’ feelings about safety, acceptance, and belonging at school.

The assessment includes items about how a student’s race/ethnicity or cultural identity affects their experiences, including whether they feel their identity is reflected in the academic curriculum.

Assessments that Are Strong in This Area:

Cultivate

Inventory of School Climate

NJ SCI Survey

Panorama SEL Survey

Elevate

School Climate for Diversity

SAESECI

EDSCLS

Developing an equity-minded assessment that uses an anti-racist or liberatory framing ensures that the assessment identifies students’ strengths and acknowledges the barriers they face. Traditionally under-represented students are often most harmed by framing that focuses on “fixing” them. Therefore, selecting an assessment that is designed to recognize students’ strengths and barriers, rather than where students’ social and emotional skills might be lagging, is crucial because it gives decision-makers the information they need to effectively meet the needs of all students. Assessments that overlook the challenges faced by traditionally under-represented students — such as students of color, students from low-income backgrounds, and multilingual learners — won’t yield information that can be used to truly improve these students’ experiences and social and emotional development

To best support these students, leaders should look for an assessment that clearly acknowledges systemic inequities and how they affect SEAD. For example, Self-Assessing Educator Social and Emotional Competencies and Instruction (SAESECI) asks teachers to reflect on the language they use in their classroom and, in the guidance on responding to results, discusses how acknowledging and accepting students’ home languages and lived experiences can help students feel that their cultures and identities are valued.[10]

Additionally, leaders should look at whether developers used an asset-based lens to identify the purpose of the assessment. The developers who designed the SAESECI, for example, describe the aims of this assessment as helping educators to reflect on their own social and emotional competencies, create conditions and implement practices that support students’ social and emotional development, and guide educators toward more personalized professional learning. This asset-based approach emphasizes continuous growth for educators, rather than identifying their deficits, and further recognizes the practices and conditions that can support students’ social and emotional well-being.

Finally, leaders should assess whether developers provide clear examples of how assessment results can inform policy and practice changes that address equity issues. Catalyze, for example, offers guides with equity-focused examples for each assessment section. The guide on Transformative Equity includes a list of research-based practices — such as eliminating the use of words like “gap” that obscure anti-Blackness — as well as a specific activity that can be used to engage educators in learning about the social and political context of the current education system.[11]

Leaders should also consider whether assessment items are written from a strength-based perspective. Assessment items should be positively framed and focus on students’ strengths — rather than deficits or negative behaviors. This will help ensure that the resulting work to address SEAD also identifies and builds up students’ strengths.

Leaders should look for assessments in which all or most assessment items use framing that focuses on what students do well, even in difficult situations. For example, an item from the Panorama SEL Survey asks, “How often are you able to control your emotions when you need to?” Framing the question in this way allows students to appreciate and reflect on their own strength and ability to control their emotions rather than on times when they may not have been able to do so.[12] Many assessments have items that focus on students’ experiences rather than their competencies and actions, but leaders should look for framing that focuses on the student’s own experiences and feelings rather than the negative behavior of other students. Figure 1 below highlights more examples of deficit-based vs. strength-based framing.

Some SEAD assessments, particularly school climate assessments, include items about school safety, such as questions about violence, weapons, and substance abuse. None of the assessments we reviewed used entirely strength-based approaches for these questions. Considering that adults in a school building shape school climate, one approach to these questions is to examine how adults provide support for these issues and whether students feel comfortable seeking help for them, as the final example in the table below and this item from the EDSCLS both do: “At this school, there is a teacher or some other adult who students can go to if they need help because of sexual assault or dating violence.”[13] Positively framing items around adult actions or systems within a school could also encourage students to visualize what an ideal education looks like. For example, an item from 5Essentials says, “Teachers work hard to make sure that all students are learning,” which suggests that it is important for students to feel that their teachers are committed to their learning.[14]

Watch Out for

What does it mean for an assessment to be rooted in equity?

It is important for assessments to have an overall purpose that centers equity and recognizes the systemic barriers that students face, but that is not enough. To be firmly rooted in equity, assessment items must also use strength-based framing.

If an assessment’s stated purpose is to prioritize equity (e.g., the purpose of the assessment is to identify students’ strengths and the barriers they face), but the assessment’s questions are focused on what students are doing wrong, it runs the risk of reinforcing deficit-based views of students and misses the opportunity to draw on student strengths. For example, if the assessment has a question that asks if students struggle with communication skills, the focus remains on the deficits of students. However, if the question asks if students excel with communication skills, the focus shifts to the strengths of students, and those identified with excellent communication skills could be encouraged to pursue student leadership opportunities in a school.

Likewise, if an assessment includes strength-based and positively framed questions throughout (e.g., How often did the child do something nice for somebody?”), but guides educators and leaders to use the information collected to identify students who are scoring lower on the assessment as in need of SEL instruction, the assessment is focused on identifying students with deficits, and therefore not rooted in equity.

Research shows that assessment data can perpetuate teachers’ deficit-based views of students — particularly students of color, low-income students, multilingual learners, and students with disabilities — [15],[16] so adopting asset-framing in both the purpose of the assessment and in the framing of the questions in the assessment is crucial. Assessments that are equity-minded consider the barriers that students face and how students can be supported at school.

To be truly focused on equity and the full spectrum of SEAD, assessments should consider more than just student skills and behaviors. Focusing solely on students’ skills can lead to an emphasis on “fixing” children rather than understanding how to support them and meet their individual needs. Instead, assessments should gather information on students’ day-to-day experiences and how they feel at school. That information can then be used to implement an equitable approach to SEAD that is focused on addressing policies and adult actions that impact students. See EdTrust’s 2020 report on “Social, Emotional, and Academic Development Through an Equity Lens” for more details about the need for this approach.

Leaders should seek assessments that primarily focus on students’ experiences — including their feelings about safety, acceptance, and belonging at school — rather than on their competencies and skills. Because race, ethnicity, and cultural identity can affect how students are perceived and treated in school, leaders should look for assessments that cover these topics, including whether students feel their identities are accepted at school and reflected in the academic curriculum. Most of the school climate and learning condition surveys we reviewed included items on these topics. For example, an item in Elevate says, “This teacher makes sure different backgrounds and perspectives are valued,”[17] an item in the EDSCLS for students says, “I feel like I belong,”[18] and an item in the SAESECI says, “I am aware of how my perceptions of student behaviors and my responses (positive and negative) affect my interactions with my students.”[19]

For leaders to determine if an assessment is right for their needs, developers must provide clear information about how an assessment should be used, including who should take the assessment and who should use the results. There are many different assessments in the SEAD space. Some are designed to help teachers improve learning conditions in their classrooms; others are designed to give district leaders a picture of school climates in their district. Having clear information allows leaders to select an assessment that is appropriate for their needs and ensure that they are using it in the context for which it was designed.

For leaders to determine if an assessment is right for their needs, developers must provide clear information about how an assessment should be used, including who should take the assessment and who should use the results. There are many different assessments in the SEAD space. Some are designed to help teachers improve learning conditions in their classrooms; others are designed to give district leaders a picture of school climates in their district. Having clear information allows leaders to select an assessment that is appropriate for their needs and ensure that they are using it in the context for which it was designed.

4. Are developers clear about the context in which the assessment should be used?

What To Look For:

The developer clearly identifies who should use an assessment, such as district leaders or classroom teachers.

The developer clearly outlines the specific purpose of the assessment and provides details on how it can be used.

The assessment and associated materials clearly align with the purpose identified by the developer.

The developer provides clear information about the appropriate level at which to use an assessment and the level of data that will be supplied — such as whether data will be for a whole school or whether it can be disaggregated by classroom or demographic group.

Assessments That Are Strong in This Area:

EDSCLS

5Essentials

Catalyze

Cultivate

NJ SCI Survey

Panorama SEL Survey

Elevate

SAESECI

5. Does the developer offer a set of assessments to capture multiple perspectives?

What To Look For:

The developer offers multiple assessments to capture multiple perspectives — including those of students, families, and educators — and these assessments are designed to work together to provide a comprehensive picture.

The developer provides resources or tools to help interpret and integrate data from multiple perspectives.

Assessments That Are Strong in This Area:

EDSCLS

5Essentials

NJ SCI Survey

Different types of SEAD assessments are designed for different contexts and different purposes, so leaders must be able to find and understand this information to select assessments that best match their school’s or district’s needs. For example, those seeking an assessment of individual students’ social and emotional competencies should search for an assessment designed with this purpose in mind, such as the Panorama SEL Survey, while those seeking an assessment of learning conditions in the classroom should select an assessment designed for that purpose, such as Elevate or Cultivate.

Leaders should seek assessments with a clearly defined purpose that is reflected in the assessment items and materials from the developer. For example, the developer of the SAESECI lists five specific aims for this assessment, including “to provide a mechanism for educators to reflect on their own social and emotional competencies” and “to provide a tool to understand the educator’s ability to promote student SEL through instructional practices.” These goals are clearly reflected in the assessment — which includes items like, “I take time to reflect on my own biases, assumptions, and knowledge and how they influence my expectations and interactions with students”— and associated guidance, and offers research-based resources for instructional practices that promote SEL.[20]

Leaders should also look for detailed guidance about the context in which the assessment should be used — e.g., at the school or district level — and who should use the results — e.g., school leaders or classroom teachers. The developer should also be clear about what kind of data will be available to users — such as whether only school-level data will be available or whether the data will be disaggregated by student group or classroom. For example, the EDSCLS website clearly outlines how the assessment should be administered at the school level, who should take the assessment, and what data, including disaggregated data, will be provided to schools, districts, and states.[21]

Assessments that capture the perspectives of students, teachers, staff, and families allow leaders to get a full picture of how schools can enhance their efforts to support students’ SEAD and can help identify discrepancies in how different groups perceive the school environment. Gathering student perspectives is crucial for measuring SEAD, but it is also important for leaders to seek the perspectives of students’ families to understand whether a school is successfully building relationships and partnerships that foster SEAD. Capturing teacher and staff responses helps leaders to understand how staff feel about the school’s current efforts. If staff feel safe and supported at school, they are better equipped to create the best climate for students. Leaders can elect to combine different assessments of different groups, but assessments that offer versions designed to work together and include guidance on how to interpret and use to the results collectively are ideal. To ensure that assessments are inclusive and gather a multiplicity of perspectives, developers should also provide assessments in multiple languages — particularly Spanish, as 76% of the country’s 5.3 million multilingual learners speak Spanish at home.[22]

Leaders should look for assessments that capture multiple perspectives, including those of students, families, and educators, to ensure that the perspectives of all stakeholders are included, as some stakeholders may hold differing perspectives. Furthermore, these assessments should be designed to work together to provide leaders with data that can be triangulated, compared, and used to make decisions that will positively impact all stakeholders. The EDSCLS, for example, includes surveys for students, instructional staff, non-instructional staff, and parents, and these surveys cover similar issues and are designed to work together. The U.S. Department of Education also provides a data interpretation guide on how to analyze the responses of different groups and make sense of all the data. Leaders should also look for assessments in languages that meet the needs of their communities. For example, the NJ SCI Survey is offered in 33 languages, and the developer also provides a point of contact for requests for other languages.[23] Additionally, some distinct assessments may be designed to work well together even if they aren’t offered as a single suite. For example, Elevate, Catalyze, and Cultivate are designed for different respondents and work well together to provide a comprehensive picture of various stakeholders’ experiences.

While academic assessments must meet high standards of technical quality to be adopted by states or districts, most SEAD assessments have not been subjected to the same level of scrutiny. Most states and districts have psychometricians to consult on academic assessments; however, they are often not investing the same expertise in SEAD assessments. Implementing evidence-based SEAD starts with using assessments that have been validated and proven to be reliable for all students — particularly for under-represented student groups. There are multiple ways of assessing reliability and validity for assessments, so there will be variability in the methods and statistical measures developers use for this purpose. However, there should be a minimum threshold of validity and reliability that has been evaluated for assessments in the SEAD space, and the following questions can provide guidance to leaders in identifying a high-quality, valid assessment.

While academic assessments must meet high standards of technical quality to be adopted by states or districts, most SEAD assessments have not been subjected to the same level of scrutiny. Most states and districts have psychometricians to consult on academic assessments; however, they are often not investing the same expertise in SEAD assessments. Implementing evidence-based SEAD starts with using assessments that have been validated and proven to be reliable for all students — particularly for under-represented student groups. There are multiple ways of assessing reliability and validity for assessments, so there will be variability in the methods and statistical measures developers use for this purpose. However, there should be a minimum threshold of validity and reliability that has been evaluated for assessments in the SEAD space, and the following questions can provide guidance to leaders in identifying a high-quality, valid assessment.

6. Were assessment items probed/validated via interviews with diverse groups of the intended respondent type?

What To Look For:

The developer gives detailed information about the development process of the assessment, including interviews.

The developer conducts cognitive interviews with diverse participants and provides demographic information.

Assessments we found to be strong in this area:

School Climate for Diversity

DESSA

Cultivate

7. Are the items written with language appropriate for the intended audience?

What To Look For:

The developer provides information on how they determined age appropriateness, such as consulting research and experts or testing with students of different ages.

The developer provides the specific reading level of the survey items.

Assessments we found to be strong in this area:

School Climate for Diversity

Inventory of School Climate

Panorama

Cultivate

Elevate

8. Was the assessment piloted with diverse participants?

What To Look For:

The developer conducted pilot testing with diverse participants (including racially/ethnically and economically diverse students, as well as other student groups such as students who identify as LGBTQ+, multilingual learners, and students with disabilities) and reports data on the diversity of pilot participants.

If the assessment was developed for educators, it was piloted with diverse educators who also work with a diverse group of students.

Assessments we found to be strong in this area:

Elevate

Cultivate

NJ SCI Survey

Panorama SEL Survey

9. Have latent variables been psychometrically validated with a statistical measure showing a good fit?

What To Look For:

The developer provides information about how the assessment was validated, ideally with a full validation report.

The developer provides a statistical measure of validation for latent variables (i.e., a set of questions aimed at measuring a construct), that meets the standard for a good fit.

Assessments we found to be strong in this area:

School Climate for Diversity

5Essentials

Inventory of School Climate

NJ SCI Survey

Panorama SEL Survey

10. Is the assessment reliable across diverse groups of respondents?

What To Look For:

The developer provides analysis showing that the assessment items function similarly for respondent groups, including race/ethnicity, students from low-income backgrounds, LGBTQ+ students, and multilingual learners.

The developer includes information about validation for each respondent group, such as an RMSEA or Rasch analysis for each respondent group.

The developer provides a measure such as Cronbach’s alpha of 0.7 or higher showing internal consistency across groups or differential item functioning at 0.64 or below.

Assessments we found to be strong in this area:

EDSCLS

Inventory of School Climate

Cultivate

Ideally, assessment items will have been developed and validated through interviews or focus groups with a diverse group of students or other intended respondents. This ensures that the language has been tailored to the assessed population and that responses reflect what items are attempting to measure. Additionally, respondents of different cultural backgrounds may interpret language from assessment items in different ways or express themselves differently in responses. Conducting open-ended interviews allows participants to give input into the assessment development process and help to identify areas where the assessment may need adjustments.

The focus group or interview process should be discussed in materials about the development and validation of the assessment and leaders should specifically look for demographic information of interview participants to be reported. We did not find any of the assessments we reviewed to fully report on this process, but two did discuss it to some extent. For example, Dr. Christy Byrd, the developer of School Climate for Diversity, references her prior work where she tested survey items and discusses conducting follow up interviews and focus groups with students at a predominantly Black school and a predominantly white school.[24] The developers of DESSA shared in conversation with us that they conducted cognitive interviews to test items with a diverse group of students; however, the information about the process is not available in the documentation about the assessment. Leaders should ask for detailed information about this process when it is not provided in assessment materials.

Assessments should be specifically designed for the target population to provide valid results. Students of different ages have different understandings of terminology related to SEAD, and items also need to be at the appropriate reading level. Similarly, assessments designed for adults (i.e., teachers, staff, or students’ families) need to have language tailored for the specific intended audience, because educators and caregivers may also have different understanding of terminology related to SEAD.

Developers must report information on how they considered age-appropriateness when developing the assessment. Ideally, developers will include information about consulting experts and existing research on language for the assessment’s intended population. The developers of the Panorama SEL Survey, for example, had experts assess items on their survey to make sure they were appropriate for lower reading levels.[25] The developers also used guidance on child-friendly words about emotions and consulted parents, educators, and survey experts.[26] The Panorama SEL Survey offers versions for grades 3-5 and 6-12 with language and items adjusted to be appropriate for each age group.

Leaders can also look for information about how the developer adjusted language after testing items with different groups aligned with the intended audience. For example, the developers of Catalyze provide information about how they adjusted items to make the language clearer after conducting interviews with educators, the intended audience for the assessment.[27]

Ideally, developers would also provide the specific reading level of the survey items, but none of the developers for the assessments we reviewed did so.

Most student assessments that we reviewed were targeted toward students in grades 3 and up. School climate assessments are not typically targeted to K-2 students. Since these students are still affected by the school climate, it is crucial that more research is done in this area to find ways of getting feedback from these students in developmentally appropriate ways.

Assessments should be piloted with diverse participants to ensure that they are reliable across student groups and are appropriate to be used in any school. Including and collecting demographic information about pilot participants allows developers to disaggregate data and examine the validity of the assessment for each group as they may have different understandings of SEAD. In addition to racial and ethnic diversity and income level, equity-focused assessments should include students who identify as LGBTQ+, multilingual learners, and students with disabilities. Assessments with an intended audience of educators and school staff should also be tested with diverse participants, as staff members’ own identities and understandings of SEAD can affect assessment results. Additionally, these assessments should be tested with staff who work with diverse student groups to make sure that they are valid to be used in any school.

Leaders should look for developers to collect and report demographic information of pilot participants. Some developers explain how they included participants from diverse groups, for example, by piloting in schools with different demographic makeups, but did not collect student-level demographic data. Since this does not allow for comprehensive reliability testing, leaders should look for assessments that did collect this data.

While most developers that collect data include students of color and students from low-income backgrounds, leaders should look for assessments that include more student groups. For example, the developers of Cultivate provide a research report including the full gender and race/ethnicity demographics of pilot participants and also explain that they collected data on free lunch status, language spoken at home, and disability status so that these characteristics could be included in the validation process.[28] While the NJ SCI Survey collects data on students who identify as transgender or nonbinary and included them in pilot testing,[29] we did not find any assessments that included LGBTQ+ students more broadly in pilot testing nor did we find any assessments that included students with disabilities.

Psychometric validation is standard for academic assessments, and there should be a similar standard of validation for SEAD assessments to ensure they accurately measure what they claim to measure. Many SEAD assessments involve latent variables, which measure concepts that can’t be measured directly and are therefore inferred by a set of questions that capture observable characteristics of the concept. For example, motivation is not something we can directly observe, but it can be inferred by a set of questions that capture aspects of student motivation such as enthusiasm to learn new things, feeling driven to excel academically, and finding studying to be rewarding.

While many districts do not have someone with psychometric expertise on staff, most states have psychometricians on staff working on academic assessments. State leaders can offer technical assistance from these experts to districts to help review an assessment’s validity. Leaders can also seek outside assistance, such as consulting university researchers or federal technical assistance centers.

Leaders should look for a developer to provide a validation report with information about how the assessment was determined to be statistically valid. For example, the developers of the EDSCLS offer a full report on how pilot testing was conducted and how the results were used to determine validity.[30]

In addition to providing a validation report, developers should also provide evidence that they’ve determined that any latent variables used are measuring what they intend to measure.

Validation versus Correlation with Academic Outcomes

Some developers focus on whether SEAD assessment outcomes influence academic outcomes rather than, or in addition to, whether they are valid measures of SEAD. For example, the developers of Elevate provide research on how survey responses predict students’ course grades.[34] We heard this reflected in our conversations with assessment developers who expressed that education leaders are more concerned about whether an assessment has been proven to predict academic outcomes, such as course grades or standardized test scores, rather than whether the assessments have been rigorously tested for validity. While we want SEAD assessments to be connected to positive academic outcomes, it is more important that they are valid and give accurate data about student experiences. Applying an equity lens, it is important for students to have positive experiences and holistic development at school and not just that they achieve academically. It is crucial to students’ development that they feel safe at school and have a sense of belonging. Positive academic outcomes should not come at the cost of students feeling as though their identity is accepted at school

Supporting Students with Disabilities

Students with disabilities deserve high-quality experiences at school and they must be included in SEAD assessment efforts. In academic assessments, students with disabilities, particularly those with cognitive disabilities, are often routed to alterative assessments — in the SEAD assessments space, they are often ignored. Only two of the assessments we reviewed considered the perspectives of students with disabilities and while some collected data on disability or special education status during pilot testing, they did not include these students in interviews or conduct validation of latent variables with specific consideration of these students.

The same way SEAD assessments should include questions about whether students feel their cultural identity is accepted and reflected at school, assessments should include items focused on whether students with disabilities feel supported at school when they experience any bias or discrimination. For example, the NJ SCI survey includes the question “Students at this school include students with disabilities in groups and activities” and the EDSCLS includes the question “The programs and resources at this school are adequate to support students with special needs or disabilities” on the survey for parents.[35]

Leaders should also look out for assessments that address disability in problematic ways. The only assessment we reviewed that substantially considers students with disabilities is DESSA; however, the materials of this assessment imply that the purpose is to identify students who need special education services, which researchers agree is not appropriate use of assessments focusing on social and emotional skills.[36] The developer uses the correlation of scores with students identified as receiving special education services in the “severely emotionally disturbed” category as evidence that the assessment is valid.[37] The developer also suggests using the information in student reports to develop Individual Education Programs (IEPs), documents outlining special education services for students with disabilities and states that Tier 3 of their accompanying programming, designed for those that the assessment labels as in need of instruction, is for students receiving special education services.[38]

Developers must consider students with disabilities in the design and testing of assessments. For example, assessment items and any guidance for interpretation should recognize that there are multiple ways of feeling or expressing emotions. We did not find any developers that offered support in making assessments accessible to students with disabilities beyond directing leaders to offer typical accommodations such as extended time. The developer of the EDSCLS states that the survey is not designed to accommodate students with severe cognitive disabilities who typically require alternative assessments and that leaders should consider whether these students are ineligible to participate.

We should continue to advocate for better inclusion of students with disabilities in SEAD assessments. In the meantime, it is important for leaders to understand the SEAD experiences of this group of students. Therefore, leaders should include students with disabilities and support them in participating in SEAD assessments. This can include typical accommodations such as one-on-one delivery of the assessment, support in understanding, or modification of answer scales.

In addition to conducting pilot testing with diverse participants, assessment developers should report the pilot test results and reliability measures for different groups of respondents — whether an assessment is aimed at students, educators, or families. To ensure that SEAD assessments meet the needs of all students, leaders should look for details from the developer about how the assessment was determined to be reliable across diverse groups of respondents.

Assessment results will differ across groups of students, as different students experience school differently. These differences in disaggregated results are useful for leaders to identify and address disparities in students’ experiences. However, for this data to be legitimate, an assessment must be reliable for all groups of respondents, showing that the items work consistently across diverse groups. Many assessment developers provide analyses about how assessment results vary across different groups, but few provide information on how the assessment items were determined to be reliable for all groups of students.

Ideally, leaders should look for the measures discussed above in Question 9 for each group of respondents including race/ethnicity, gender, income level, LGBTQ+ status, and multilingual learner status. We did not find any assessments that provided this information comprehensively for each group.

Leaders can also look for other statistical measures that compare item fit across different groups.

This section of the framework focuses on the guidance that developers provide on how to successfully implement an assessment and use it to improve SEAD outcomes for students. Larger districts with more resources may have staff with SEAD and/or statistics expertise who can implement assessments and interpret results without this guidance. Comprehensive developer-provided guidance and tools can make it easier for all school leaders and educators, especially in smaller or under-resourced districts, to understand assessment results and identify research-based changes to make in their practice. Part three of this guide will discuss best practices in using assessment data to make decisions and practice changes — including engaging students and other stakeholders in the decision-making process. The guidance and tools offered by developers are valuable, but it is important that they are a part of that decision-making process and do not supersede engaging stakeholders and examining results alongside other data to make informed decisions.

This section of the framework focuses on the guidance that developers provide on how to successfully implement an assessment and use it to improve SEAD outcomes for students. Larger districts with more resources may have staff with SEAD and/or statistics expertise who can implement assessments and interpret results without this guidance. Comprehensive developer-provided guidance and tools can make it easier for all school leaders and educators, especially in smaller or under-resourced districts, to understand assessment results and identify research-based changes to make in their practice. Part three of this guide will discuss best practices in using assessment data to make decisions and practice changes — including engaging students and other stakeholders in the decision-making process. The guidance and tools offered by developers are valuable, but it is important that they are a part of that decision-making process and do not supersede engaging stakeholders and examining results alongside other data to make informed decisions.

Supporting Teachers in Implementing SEAD Assessments

In responding to assessment results, leaders should support educators rather than place additional burdens on them. Many of the practice changes and interventions that developers recommend in responding to assessment results require teachers to take time to reflect on current practices, change classroom procedures, and build relationships with students and families. Teachers may feel overwhelmed if they are tasked with these interventions without being given appropriate time, training, and supports to do so. A recent report from RAND showed that teachers reported experiencing burnout at twice the rate of similar working adults, with Black teachers in particular reporting working significantly more hours than their peers.[42] With this in mind, leaders should find ways to ensure teachers are supported in SEAD efforts rather than adding additional burdens.[43]

11. Do the developers offer a tool to easily interpret and understand the assessment data?

What To Look For:

Assessments we found to be strong in this area:

EDSCLS

5Essentials

Catalyze

DESSA

NJ SCI Survey

Panorama SEL Survey

Elevate

Cultivate

12. Have developers identified how assessment results are connected to policy and practice decisions?

What To Look For:

Assessments we found to be strong in this area:

EDSCLS

Catalyze

NJ SCI Survey

Elevate

SAESECI

Cultivate

Leaders, particularly those in schools or districts without in-house data expertise, often need guidance and tools to help interpret and understand the assessment data. Therefore, resources like a user-friendly data interpretation guide, platform, or tool can help the educators involved in the process to understand and respond to the results. These resources should include the disaggregation of data by student group, as long as a minimum n-size is met to protect student privacy, so that educators can identify and address inequities in the data — resources that do not allow for disaggregation will hide inequities within a school or a classroom. For example, while overall averages from a school climate survey may show a positive school climate, disaggregated data would likely show that some student groups, such as students of color, are not having the same experience as other students.

Leaders should look for a user-friendly tool, platform, or reporting system that allows educators or decision-makers to access and understand assessment data. Data visualization in particular is ideal for helping users to understand trends in the data. For example, Elevate offers a platform that allows teachers to generate graphs of the data for each learning condition and allows them to disaggregate the data by gender and race/ethnicity.[44]

It is important to help leaders improve SEAD in their schools rather than merely measuring it. Guidance on how to connect assessment results to practice and policy changes can help leaders with those efforts. While leaders in states or districts with access to SEAD specialists may feel comfortable identifying and implementing appropriate research-based responses to assessments that do not provide significant guidance, districts and states that do not have SEAD expertise should look for an assessment that provides research-based guidance and resources.

Leaders should look for developers to provide guidance and resources for making policy and practice decisions to respond to the data from each assessment item or section of assessment items. The guidance should be rooted in equity, call out biases and systemic inequities, and should be research-based with links or citations for specific evidence. This type of guidance can be integrated into a tool, platform, or data interpretation guide. For example, the USED Climate Survey provides a data interpretation guide that walks users through how to respond to assessment results. The guide suggests that educators can respond to results showing that students are being bullied due to their race or ethnicity by incorporating culturally diverse examples in lessons and materials.[45] Additionally, note that certain tools (e.g., Elevate and Catalyze) facilitate longitudinal data tracking for continuous improvement purposes. Such tools are specifically designed to help practitioners quickly assess whether—and for whom—intended improvements have had the desired effects. For example, they enable practitioners to conduct multiple, rapid tests over the course of a single school year or semester.

No current single SEAD assessment can fully illustrate what is happening in schools. For example, a district might be using a school climate survey that gives them data about students’ experiences, but that assessment may not have data on whether teachers feel supported by the administration. To create a complete picture, state and district leaders must produce a comprehensive system of SEAD assessments that, when used together with other existing data, gives practitioners and policymakers the information they need to make continuous improvements. Here, we provide considerations for creating a system of assessments that can depict what is happening in schools.

No current single SEAD assessment can fully illustrate what is happening in schools. For example, a district might be using a school climate survey that gives them data about students’ experiences, but that assessment may not have data on whether teachers feel supported by the administration. To create a complete picture, state and district leaders must produce a comprehensive system of SEAD assessments that, when used together with other existing data, gives practitioners and policymakers the information they need to make continuous improvements. Here, we provide considerations for creating a system of assessments that can depict what is happening in schools.

A theory of action presents the logical argument of how a policy initiative will create intended outcomes and reach intended goals. It identifies how these goals will be met and what roles various stakeholders have in achieving those goals. Creating a theory of action for the system of assessments can help align stakeholders, connect data collection and analysis methods to each phase of the logic model, and to ensure the data and analysis of the system of assessments leads to actionable decisions that improve outcomes. The theory of action can also help leaders at the school, district, and state levels to develop a shared understanding of the roles that they each play and how they work together to improve students’ experiences.

When determining purpose and developing a theory of action, it is important to consider the appropriate use of SEAD assessment data in accountability systems. Most SEAD assessments have not been sufficiently validated or vetted and most are observational or self-report surveys that more inherently allow biases to influence the data.[46] Research suggests that leaders and educators are less likely to engage with SEAD data, or more likely to misuse or distort it, if they feel that it will be used in a punitive way,[47] while school leaders are more likely to be transparent with data and share it with district leaders if they feel it will be used to support them.[48] Therefore, SEAD data should not be used to rate schools or evaluate teachers. Instead, the most appropriate uses of SEAD assessments are to identify which schools require more supports and resources for continuous improvement and communicating progress to stakeholders.[49]

Example:

The Illinois State Board of Education developed a detailed theory of action for its state systemic improvement plan that recognizes the goals of the system, the root causes of outcomes the state is focused on, and how the inputs the state provides are hypothesized to impact short-term and long-term outcomes. Importantly, the logic model includes a focus on how assessments will be used (e.g., the state will determine capacity for implementing and sustaining a MTSS framework with fidelity by using an assessment tool that identifies school readiness level) and how the data from those assessments will be used for decision-making.

The system of assessments should cover all aspects of SEAD that are necessary areas of focus – as determined by the theory of action so that school and district leaders have sufficient information to make schoolwide and districtwide decisions for improvement. There are several aspects of SEAD that can be captures by different types of SEAD assessments.

Students’, families’, and educators’ perspectives must all be included in the system of assessments to best understand the schools’ educational environment. Data is strongest when representative of all stakeholders, when it can be analyzed to see if various perspectives are aligned, and when it can be used to understand the causes for any discrepancies in perspectives. For example, students might report feeling that they are treated differently because of their race/ethnicity, but teachers in the same school report that they have not seen any evidence of students being treated differently. This comparison of data could suggest that educators need more support identifying their own biases and examining their own interactions with students.

Leaders should be mindful that assessments take time and resources and ensure that assessments do not duplicate efforts — the system of assessments should not overburden the communities they are meant to improve outcomes for. For example, leaders should not have more than one assessment focused on learning conditions or more than one assessment that is aimed at parents or family members of students. In addition, assessments should only be administered as often as is needed — balancing the need for more frequent administration to gather up-to-date data for continuous improvement and minimizing the burden that multiple administrations places on teachers and students. To support their communities, leaders should consider what other data can be used in conjunction with the system of SEAD assessments, such as discipline or chronic absenteeism data.

Data is not neutral, nor will it change things on its own. Data — including SEAD data — must be used as part of ongoing continuous improvement processes, where stakeholders work toward addressing a specific problem in an iterative cycle of identifying and testing practices, collecting and analyzing data, evaluating results, then refining practices.[50] When using SEAD data in efforts to change policy and practice, district and state leaders must be intentional about how data is analyzed, interpreted, and used to ensure those processes support students’ social, emotional, and academic development. In conversations with state and district leaders,[51] they underscored the importance and challenges of engaging in meaningful, equity-based data use. Based on those reflections, and a review of relevant literature,[52] we offer a set of considerations for using SEAD assessment data to change practice and improve students’ experiences. These considerations represent a set of grounding concepts that should guide further research — with key stakeholders, including practitioners — to develop specific guidance about how these considerations could be implemented in context:

Data is not neutral, nor will it change things on its own. Data — including SEAD data — must be used as part of ongoing continuous improvement processes, where stakeholders work toward addressing a specific problem in an iterative cycle of identifying and testing practices, collecting and analyzing data, evaluating results, then refining practices.[50] When using SEAD data in efforts to change policy and practice, district and state leaders must be intentional about how data is analyzed, interpreted, and used to ensure those processes support students’ social, emotional, and academic development. In conversations with state and district leaders,[51] they underscored the importance and challenges of engaging in meaningful, equity-based data use. Based on those reflections, and a review of relevant literature,[52] we offer a set of considerations for using SEAD assessment data to change practice and improve students’ experiences. These considerations represent a set of grounding concepts that should guide further research — with key stakeholders, including practitioners — to develop specific guidance about how these considerations could be implemented in context:

What the Research Says: As with overall approaches to SEAD, SEAD assessment results can be used to perpetuate the false idea that students have skill deficits in need of correcting. Researchers cite concerns that assessment results can be used in ways that stigmatize children and emphasize that cultural narratives affect how educators view racial and gender gaps in assessment data.[53] Research also shows that teachers can misuse data to perpetuate deficit-based views of students, particularly students of color, students from low-income backgrounds, English learners, and students with disabilities.[54]

What We Heard from State and District Leaders: State and district leaders recognize the importance of considering systemic inequities when analyzing SEAD assessment data. While many assessments are strength-based, some assessment questions can be deficit-based by focusing on student misbehavior. Leaders noted it is important to interpret responses to questions like these through the lens of students’ experiences and how policies and practices can be changed to better meet students’ needs.

What State and District Leaders Should Do: Leaders must actively encourage and support educators to consider students’ strengths, structural barriers, and root causes of disparities when analyzing SEAD assessment data, and the learning conditions necessary for equitable student outcomes. Students bring many different experiences as they enter schools so an asset-based approach to data analysis should focus on identifying and addressing student needs connecting students and families to school-based resources, rather than blaming or judging students for their behaviors and attitudes.

What the Research Says: A data analysis protocol presents a clear plan for how data will be analyzed and compared to produce insights that illuminate students’, parents’, and educators’ perspectives on SEAD. Sometimes, data is used simply to justify previously made decisions and affirm prior beliefs, rather than being truly engaged with to make evidence-based decisions.[55]ome research suggests that educators only disaggregate social and emotional learning (SEL) data by racial groups when specifically required to.[56]

What We Heard from State and District Leaders: State and district leaders spoke of the many teams, offices, and stakeholders who manage SEAD assessment data collection and analysis. Some state leaders provide guidance and protocol for district leaders to ensure they understand what the data means and how to appropriately measure what student groups may require more support. However, protocols for how to manage data are not always required or mandated, leaving many stakeholders unclear about how to identify inequities in data disaggregation. One district leader emphasized the need for triangulation of data points as well as access to individual data. It is paramount that stakeholders have access to data systems that aggregate data from multiple sources to capture a more complete picture of trends in assessment data.

What State and District Leaders Should Do: Leaders should create a specific data analysis protocol and a routine to review data regularly. In addition to race and ethnicity, we recommend that data should be disaggregated by gender, English learner status, disability status, and socioeconomic status, as well as, ideally, students who identify as LGBTQ+. In addition, protocols should include intersectional analyses of students, as students’ different identities can affect their sense of belonging and perception of school climate. Whoever is involved in the process — be it district-level officials, administrators, or teachers — should have training to develop a strong understanding of the protocol.

What the Research Says: Many schools and districts do not have a data expert on staff or otherwise lack the capacity to carry out the full data analysis and review process to understand what SEAD assessment data can tell them about needed policy and practice changes. Having external support is useful in navigating dynamics within schools and preventing the dismissal or misinterpretation of data. Research suggests that teachers would be more receptive to hearing about data from an external researcher and that this type of research-practice partnership can help drive equity in school improvement.[57] Research also shows that technical assistance can help school staff understand and use data with a deeper level of analysis and build more data analysis skills.[58] Research also shows that data analysis and usage increase when school leaders have access to easily understandable data reports.[59]

What We Heard from State and District Leaders: State and district leaders express that while they collect an abundance of data, challenges remain with analyzing and interpreting the data, and further translating this data for all stakeholders. Many leaders expressed a need for more supports, such as cost-effective tools and platforms that support data visualization and interpretation, and even used the availability of these supports as a determining factor when choosing SEAD assessments. State and district leaders believe all stakeholders need to understand SEAD data for it to be actionable and meaningful. One promising practice mentioned is the use of Data Summits, where all stakeholders- parents, students, community members, educators, and school leaders- come together to hold transparent conversations regarding data points and discuss what those results mean for school level policy and practice decisions.

What State and District Leaders Should Do: State and district leaders should consider what technical assistance they can offer to schools, such as developing data dashboards or providing coaches or data review sessions to help school leaders review and understand SEAD assessment data.[60] All leaders, particularly school leaders and district leaders in smaller or under-resourced districts, can also seek assistance from regional education agencies, university researchers, or federal technical assistance centers. Some assessment vendors offer customizable reports, so state and district leaders can work with school leaders to determine what they need the most when choosing what information to include.

What the Research Says: Research shows that most teachers are not involved in reviewing school climate survey results, even though teachers can be considered the primary drivers of school climate and have the most power to change students’ experiences at school.[61] Research also suggests that students should be involved in the process of data analysis and continuous improvement.[62] Students are the experts on their own experiences and can provide more context behind data points to help shape the response. In addition, teachers are less likely to dismiss data as inaccurate if they hear information directly from students.[63]

What We Heard from State and District Leaders: State and district leaders acknowledge the importance of stakeholder engagement in understanding assessment data. Several leaders mentioned the role of student voice and family engagement in the data analysis process, and the importance of transparency and clear communication to ensure all stakeholders are aligned and engaged in understanding SEAD data.

What State and District Leaders Should Do: The National Practitioner Advisory Group on Using Data to Inspire SEL Practice recommends fostering the capacity of all adults in an organization by offering workshops, identifying organizational champions to mentor others in data analysis, and encouraging staff to question current practices.[64] Students can be engaged in a variety of ways, such as focus groups, student ambassadors who join the data analysis sessions, or a student-led data summit where students analyze the data themselves and choose priorities.[65] Family engagement can occur in similar ways, with focus groups or communication and discussion of data and current SEAD policies and practices at Parent Teacher Student Association (PTSA) meetings.

At the state or district level, leaders should engage stakeholders in helping to choose priorities to focus on with SEAD efforts and to inform the development of tools and supports. This can include focus groups, discussions with student and teacher representatives on district and state school boards, and presentations and discussions at school board meetings.

[1] Skoog-Hoffman, A., Miller, A., Plate, R., Meyers, D., Tucker, A., Meyers, G., Diliberti, M., Schwartz, H., Kuhfeld, M., Jagers, R., Steele, L., & Schlund J. (2024). Findings from CASEL’s nationwide policy scan and the American teacher panel and American school leader panel surveys. RAND. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1822-2.html

[2] Duchesneau, N. (2020). Social, Emotional, and Academic Development Through an Equity Lens. EdTrust. https://edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Social-Emotional-and-Academic-Development-Through-an-Equity-Lens-August-6-2020.pdf

[3] Prothero, A. (2023, April 20). Student Behavior Isn’t Getting Any Better, Survey Shows. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/student-behavior-isnt-getting-any-better-survey-shows/2023/04

[4] Bryant, G., Crowley, S., & Davidsen, C. (2020). Finding Your Place: The Current State of K-12 Social Emotional Learning. Tyton Partners. https://tytonpartners.com/finding-your-place-the-current-state-of-k-12-social-emotional-learning/

[5] Taylor, J., Buckley, K., Hamilton, L.S., Stecher, B.M., Read, L. & Schweig, J. (2018). Choosing and Using SEL Competency Assessments: What Schools and Districts Need to Know. RAND. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.13492.30086

[6] EdTrust sought the input of an advisory group of SEAD experts, including Chris Brandt, Robert Jagers, Camille Farrington, and Deborah Rivas-Drake, throughout the project.

[7] The assessment is available in this publication: Brand, S., Felner, R., Shim, M., Seitsinger, A., & Dumas, T. (2003). Middle school improvement and reform: Development and validation of a school-level assessment of climate, cultural pluralism, and school safety. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(3), 570–588. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.3.570

[8] Allbright, T. & Hough, H. (2020). Measures of SEL and School Climate in California. National Association of State Boards of Education

[9] Bertrand, M., & Marsh, J. (2015). Teachers’ Sensemaking of Data and Implications for Equity. American Educational Research Journal, 52(5), 861-893.

[10] Center on Great Teachers and Leaders. (2022). Self-Assessing Educator Social and Emotional Competencies and Instruction. American Institutes of Research. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/2022-12/GTL-Educator-Self-Assessment-Refreshed-2014-508.pdf , p34

[11] PERTS. (2024). Transformative Equity. UChicago Consortium on School Research. Retrieved July 23, from https://drive.google.com/file/d/1LS0ooSyxiiWeJyUkUYhufKgAiJQMsPJO/view

[12] Panorama. User Guide: Social-Emotional Learning. Retrieved July 12, 2024, from https://panorama-www.s3.amazonaws.com/files/sel/SEL-User-Guide.pdf

[13] National Center for Education Statistics. ED School Climate Surveys: Student Survey. U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved July 12, 2024, from https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/sites/default/files/EDSCLS_Questionnaires.pdf

[14] UChicago Impact. (2023). 5Essentials 2023-2024 Student Survey Questions. https://impactsurveys.my.site.com/s/article/illinois-5essentials-survey-questions

[15] Allbright, T. & Hough, H. (2020). Measures of SEL and School Climate in California. National Association of State Boards of Education

[16] Bertrand, M., & Marsh, J. (2015). Teachers’ Sensemaking of Data and Implications for Equity. American Educational Research Journal, 52(5), 861-893

[17] UChicaco Consortium on School Research. Elevate: Measures Summary. Retrieved July 12, 2024, from https://docs.google.com/document/d/1vd1WC4GlqqE_AsshNFo3V-qkjzLit-nHz8L5AKMncAg/preview

[18] National Center for Education Statistics. ED School Climate Surveys: Student Survey. U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved July 12, 2024, from https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/sites/default/files/EDSCLS_Questionnaires.pdf

[19] Center on Great Teachers and Leaders. (2022). Self-Assessing Educator Social and Emotional Competencies and Instruction. American Institutes of Research. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/2022-12/GTL-Educator-Self-Assessment-Refreshed-2014-508.pdf

[20] Center on Great Teachers and Leaders. (2022). Self-Assessing Educator Social and Emotional Competencies and Instruction. American Institutes of Research. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/2022-12/GTL-Educator-Self-Assessment-Refreshed-2014-508.pdf

[21] American Institutes for Research. (2024). ED School Climate Surveys. National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments. https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/edscls/reporting

[22] National Center for Education Statistics. (2024). English Learners in Public Schools. Condition of Education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Retrieved May 30, 2024, from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cgf

[23] New Jersey Department of Education. New Jersey School Climate Improvement (NJ SCI) Survey

Compendium of Frequently Asked Questions. Retrieved August 5, 2024, from https://platform.njschoolclimate.org/files/activity/NDg=/download/pdf/New+Jersey+School+Climate+Improvement+Platform+FAQ.pdf

[24] Byrd, C.M. (2015) The Associations of Intergroup Interactions and School Racial Socialization with Academic Motivation, The Journal of Educational Research, 108:1, 10-21, DOI: 10.1080/00220671.2013.831803

[25] Panorama Student Survey: Development and Psychometric Properties. Panorama Education. Retrieved October 19, 2023 from https://go.panoramaed.com/hubfs/Files/PSS%20full%20validity%20report.pdf

[26] Reliability and Validity of The Panorama Well-Being Survey. (2021). Panorama Education. https://go.panoramaed.com/hubfs/WellBeing-Reliability-Validity-Report.pdf; Reliability and Validity of The Panorama Equity and Inclusion Survey. (2019). Panorama Education. https://go.panoramaed.com/hubfs/Validity-Report-Equity-Inclusion-Survey.pdf

[27] PERTS. (2023). Catalyze: Measures Summary & Changes. UChicago Consortium on School Research. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1Pklku6LyXlP6CqcpynzSiWpPixGtP32p45WvLOx8RLw/edit

[28] Farrington, C., Levenstein, R. & Nagaoka, J. (2013). “Becoming Effective Learners” Survey Development Project. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED563049.pdf

[29] The developers of the NJ SCI Survey shared this in a conversation with us. Rutgers University. (2023). New Jersey School Climate Improvement Survey.

[30] National Center for Education Statistics. (2015). ED School Climate Surveys (EDSCLS) National Benchmark Study 2016, Appendix D: EDSCLS Pilot Test 2015 Report.

[31] School Climate Transformation Project. (2023). New Jersey School Climate Improvement (NJ SCI) Survey Development and Validation Study Summary Report.