Campus Racial Climates Amid Student Protests: Keeping Students of Color Safe

To improve access and retention for students of color, there must be sustainable steps toward improving campus racial climates.

From book bans to arresting students for participating in nonviolent direct action, censorship has plagued our educational systems and detrimentally impacts campus climates nationwide. What student would want to go to class if they don’t feel safe and supported by their institution?

Students already face numerous barriers to success, such as college access and affordability, yet there are persistent injustices within campus climates that prevent students of color from succeeding. To improve access and retention for students of color, there must be efficient and sustainable steps taken toward improving campus racial climates — and moving away from punitive measures for students. EdTrust’s Campus Racial Climate Student Project tackles these social and systemic barriers to success for students, specifically students of color.

In the report, in which researchers interviewed students of color who attend predominantly white institutions (PWIs) to ask about their experiences on campus, a student named Parshan stated, “A lot of my friends who are people of color feel very unsafe, because; given what’s been happening in America, they feel very insecure being around the campus security, because you never know when they might shoot.”

I can relate. I was at UCLA’s encampment for Gaza in May and found myself harassed by law enforcement and counter-protesters who threatened violence against me and my friends for merely participating in protests led by faculty, staff, and students — campus stakeholders. I also witnessed students of color, who were not participating in the protests, being attacked by mobs of adults not affiliated with UCLA when they were just trying to get to class.

What was the UC system’s response to students being harassed? Placing restrictions on our ability to protest that directly harms students, like implementing mask bans. With the rise of protests on campuses and large cities, mask bans have risen because masks are assumed to be merely used to hide protestors’ identities. The ban on masks at protests is beyond dangerous for disabled students and community members that have pre-existing conditions like asthma or long COVID, and even more dangerous for disabled communities of color as we experience another COVID surge. Our universities are adopting these policies outlining where we can protest in the disguise of disability justice but fail to prioritize the physical health of disabled students.

University announcements and legislation co-opt the concepts of free speech and racial equity by only protecting white passing, able-bodied students that are not being actively impacted by structural violence due to their involvement in the art of protest. The lack of student-centered policies or actions put in place and implemented to foster a greater campus culture for students who pay hundreds of thousands of dollars to attend institutions for four years does not bode well for a sense of belonging. When looking at California’s SB 1287, organizations like the University California Student Association (UCSA), California Faculty Association (CFA), labor unions, and the American Civil Liberties Union opposed this legislation because it was not rooted in the student voice. However, schools like Brown have taken a different approach to honoring student experiences. Brown’s approach to handling disagreements between the institution and stakeholders focuses on having a conversation with students, rather than restricting their right to protest; and then later holds votes on policies that students lobbied — the UC system should take notes.

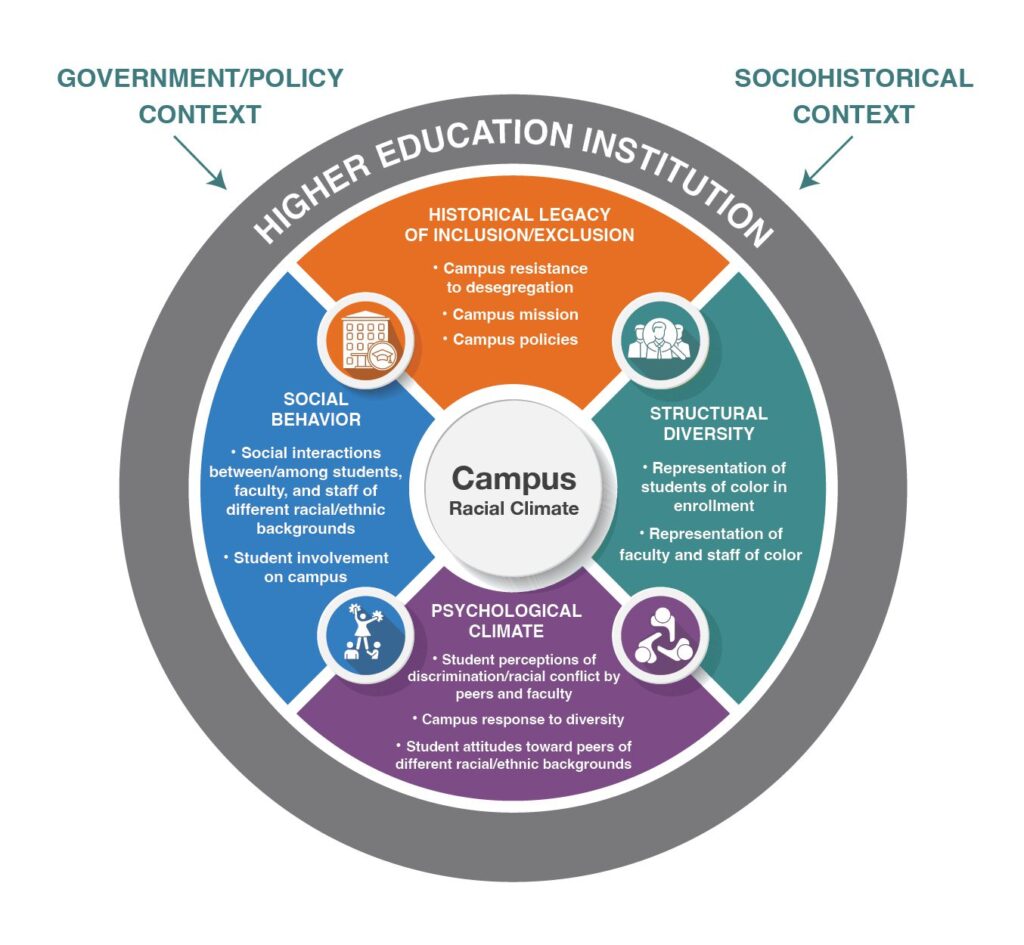

EdTrust’s Campus Racial Climate framework offers recommendations for universities to assist in creating safe and welcoming environments for students of color. The framework includes campus racial climate assessments for administrators to understand and strategize how to fill the gaps between students’ sense of belonging and their home campus along with anonymous reporting systems for students to file civil rights complaints outside of university police offices.

This year has been especially contentious with an upcoming Presidential election, numerous global wars, and state-wide policies that dismantle the power students of color have built up over the past few decades.

If students lose our voice — who will be responsible for making change?

Durriya Ahmed is a current EdTrust Higher Education Research intern and is currently a fourth-year at UCLA pursuing a bachelor’s degree, double majoring in History and Geography and minoring in Public Affairs.