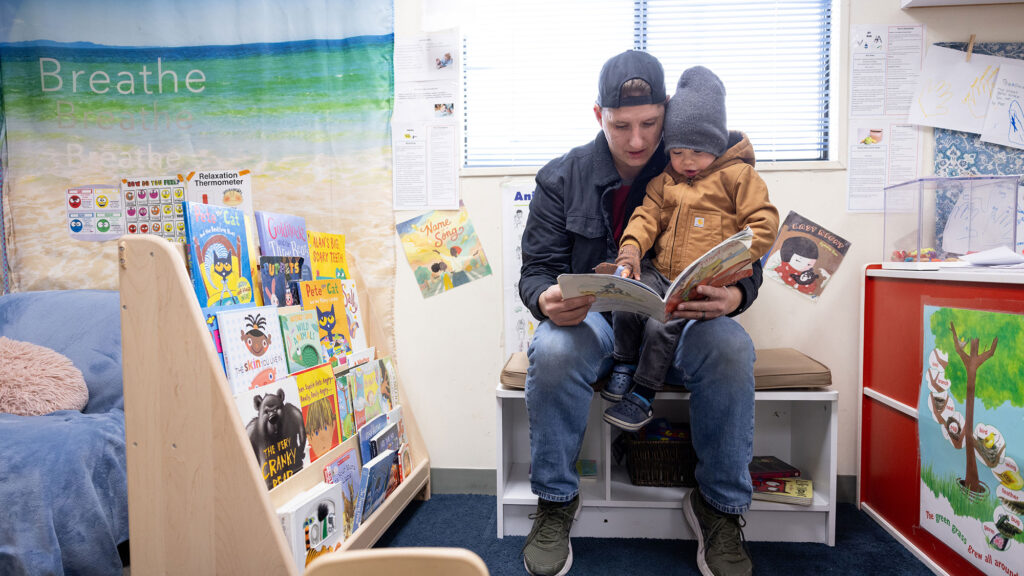

More than half of the 2020 presidential candidates support some version of “free college” as a strategy to combat the rising cost of college. Whether or not “free college” is a part of the solution, candidates, policymakers, and college leaders must do more to consider the experiences of student parents, who represent nearly 4 million undergraduates in the United States and who sit at the intersection of the college equity, affordability, and access challenges facing this country today.

Any strategies to make college more affordable should include a focus on equity. How do students who are most affected by the college affordability crisis — including students with children, low-income students, students of color, and adult students — fare in plans to establish “free college” programs? Who will benefit from these plans and who will be excluded? How will they work to alleviate existing student debt and prevent excessive borrowing moving forward—and for whom?

The national conversation about making college free is growing in prominence, and many institutions, higher education systems, and states are implementing their own free college policies, which can be loosely defined as federal, state, or local programs that cover at least tuition and fees for some or all students based on certain eligibility rules. In May 2019, for example, the Workforce Education Investment Act was signed into law in Washington State, providing free or reduced tuition for middle- and low-income students attending community colleges and public institutions. Just two months later, the University of Texas at Austin joined other institutions by providing full tuition for Texas families making $65,000 or less per year.

Proposals to establish free college vary widely by presidential candidate. Senators Warren, Harris, Sanders, and Gillibrand, for example, support free (or debt-free) college tuition and fees across all public four- and two-year institutions, while former Vice President Biden, Julian Castro, and Senator Klobuchar support covering tuition and fees at community colleges. Some candidates, such as Mayor Pete Buttigieg, suggest making college free for students with the lowest incomes, while others (like Senators Warren and Gillibrand) support a program for which all students could be eligible. As candidates’ platforms continue to develop, they should keep student parents — whose caregiving and financial demands make affordable college essential to their ability to enroll and succeed — in mind. Free college programs rarely include assistance with living expenses and child care costs, for example, expenses which student parents must cover to continue in school. (Introduced last week, Senator Harris’s BASIC Act proposal would help higher education institutions meet basic, non-tuition needs—including child care—of their students.)

Proposals to establish free college vary widely by presidential candidate. Senators Warren, Harris, Sanders, and Gillibrand, for example, support free (or debt-free) college tuition and fees across all public four- and two-year institutions, while former Vice President Biden, Julian Castro, and Senator Klobuchar support covering tuition and fees at community colleges. Some candidates, such as Mayor Pete Buttigieg, suggest making college free for students with the lowest incomes, while others (like Senators Warren and Gillibrand) support a program for which all students could be eligible. As candidates’ platforms continue to develop, they should keep student parents — whose caregiving and financial demands make affordable college essential to their ability to enroll and succeed — in mind. Free college programs rarely include assistance with living expenses and child care costs, for example, expenses which student parents must cover to continue in school. (Introduced last week, Senator Harris’s BASIC Act proposal would help higher education institutions meet basic, non-tuition needs—including child care—of their students.)

Student parents should be included in conversations about college affordability, given that they make up almost a quarter (22 percent) of all undergraduates and are more likely to be students of color (51 percent) and women (70 percent). Including student parents in the college affordability conversation is vital to achieving key educational, social, and economic equity goals. For instance, student parents often struggle with poverty while in school (68 percent live in or near poverty), and have more than 2.5 times more debt than students without children. One in three Black students are parents, the most of any racial/ethnic group, and their average undergraduate debt — $18,100 in 2015-16 — is higher than that of student parents or non-parents of every other racial/ethnic background.

Free college programs can play an integral role in meeting key workforce and economic demands, especially when they intentionally include underserved student populations, such as student parents and other working adults, who might otherwise bypass college or leave school before earning a credential that can help them earn a better living. At least 16 of the current presidential candidates come from states that have set educational attainment goals that commit to dramatically increasing the number of adults with college or workforce credentials by a target date in the 2020s. If candidates hope to help states meet or exceed these goals, they must put forward plans that actively recruit and serve students with family, work, and financial commitments.

As candidates, policymakers, and college leaders develop plans to tackle college affordability, here are a few ways that they can be sure to include student parents in their solutions:

As candidates, policymakers, and college leaders develop plans to tackle college affordability, here are a few ways that they can be sure to include student parents in their solutions:

- Reevaluate eligibility rules that can restrict student parents’ ability to participate in free college or other programs aimed at making college more affordable. Restrictive eligibility rules include those that limit participation to younger students or recent high school graduates, or to students who can enroll full-time. Transparency around eligibility rules, participation requirements, and the full cost of attendance must also be central.

- Make programs be first-dollar programs so that students can cover non-tuition costs, such as the cost of child care, family housing, food, and transportation.

- Ensure that free college programs encourage institutions to be transparent about the true cost of college, and the return on students’ investment of time and resources. For families and other working adults, knowing that enrolling in college will lead to a degree that will result in a family-sustaining wage is essential.

- Include additional supportive services — such as advising on career paths and appropriate courses to achieve desired credentials, intensive coaching both in school and at jobs during and after education is complete, emergency aid, and other specific needs student parents may have—in program design to set students up for success and ensure they can meet their basic needs while pursuing education.

Many students, including student parents, stand to gain from free college programs, as long as these programs are accessible to them. Without intentional access for student parents, free college programs could end up exacerbating some of the inequities they aim to address. Student parents are ready and motivated to succeed in college (student parents achieve higher GPAs than other students), but policymakers, including those running for the most visible policymaking position in the country, must do more to include and support them.

Susana Contreras-Mendez is a research associate at the Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR).

Tessa Holtzman is a research assistant at the Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR).

Lindsey Reichlin Cruse is a study director at the Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR).

Proposals to establish free college vary widely by presidential candidate.

Proposals to establish free college vary widely by presidential candidate.  As candidates, policymakers, and college leaders develop plans to tackle college affordability, here are a few ways that they can be sure to include student parents in their solutions:

As candidates, policymakers, and college leaders develop plans to tackle college affordability, here are a few ways that they can be sure to include student parents in their solutions: