Meet Tymika Lawrence, an immigrant and mother of three children under the age of 10. She recently earned an associate of arts degree from the CUNY Borough of Manhattan Community College before transferring, with support from the Kaplan Educational Foundation (KEF), to a four-year Ivy League university. Now at Princeton University, Tymika is pursuing a bachelor’s degree in economics. Her dream is to become a lawyer, so she can help create a more just and equitable world for her children and future generations. Here, she talks about her academic journey and some of the support she got along the way.

Meet Tymika Lawrence, an immigrant and mother of three children under the age of 10. She recently earned an associate of arts degree from the CUNY Borough of Manhattan Community College before transferring, with support from the Kaplan Educational Foundation (KEF), to a four-year Ivy League university. Now at Princeton University, Tymika is pursuing a bachelor’s degree in economics. Her dream is to become a lawyer, so she can help create a more just and equitable world for her children and future generations. Here, she talks about her academic journey and some of the support she got along the way.

Choosing to pursue a higher education is the easy part. Getting into college and getting through it is another matter. Describe your path to Borough of Manhattan Community College and Princeton University.

For me, choosing to pursue a higher education was not the easy part. When I went to college the first time around, I was 16, with undiagnosed ADHD, and I wasn’t ready to be there. I failed out after three semesters. Because I’d lost access to my scholarship after my second semester of failing grades, I couldn’t afford to pay for college and had to explore other paths. Six months after leaving university, I found myself working aboard a small cruise ship off the coast of Maine. The work was challenging, but its social nature put me on the path to discovering who I was and what was important to me.

When I came back ashore, I stumbled into work as a barista. When I realized that there was an entire industry behind a drink that most of us take for granted, I was hooked. Against all odds, I moved from retail to the professional side of the coffee business, working to connect roasters with producers. There, I saw how the colonial history of the international coffee market has led to the underrepresentation of women and indigenous coffee producers in the industry. It was challenging but fulfilling work. I was often the only person in a company who looked like me, much less who didn’t have a college degree. In late 2023, when I was laid off, I felt stuck. The workplace was a place where proving your competency without the “right” qualifications was no longer possible — AI would filter you out first.

My layoff also tugged at something deeper. Working in the coffee industry had been integral to my identity. Who was I now? I felt the need to do something, so five days after being laid off I applied to the Borough of Manhattan Community College, via the second-chance program. I initially planned to take classes full time while on unemployment and then return to work and finish my degree gradually. After my first week of classes, I realized that school was where I needed to be.

A few months later, I became pregnant with my youngest child. I knew I wanted one more child; I also knew that continuing to excel in school, without delaying my transfer journey was important to me. What I didn’t know was how I was going to achieve it. As my pregnancy progressed, I managed to keep my grades up, but I began to worry about my capacity to continue my transfer journey.

That’s where the support from KEF was invaluable. When I spoke with Kandace, the program coordinator, about my application, I laid it all out: “I’m an older student, a married mom of two, and oh yeah, I’m eight-and-a-half-months pregnant. Can your program serve someone like me?” She assured me, “We’ve served scholars with children before. You’re not even close to the oldest scholar we’ve worked with, and if you get into the program, we will work with you.”

After that, I threw myself into the process because I realized that KEF’s Kaplan Leadership Program was exactly what I needed to uphold my promise to myself. More importantly, KEF saw a future for me that I hadn’t realized was possible. They were the first to affirm that I did have what it takes to be admitted to an Ivy League university. Yes, I can attend a school like Princeton, despite being a mother. They helped me believe I belonged in such schools and guided me through the practical parts of applying — making sure my financial aid documentation was submitted on time, helping me understand the unique needs I would have as a student-parent, and what questions I should ask institutions to ensure I had everything I needed.

What drew you to law and economics?

I’ve always been interested in the law. Not being able to go to law school was my principal regret about not finishing my degree the first time around. As an immigrant, I knew from a young age that a passing familiarity with U.S. history and laws wouldn’t be enough; my ability to become a citizen depended on truly understanding them. I’ve lived in the U.S. for most of my life and I’ve been a citizen for many years, but I remember taking a practice citizenship test from the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) with a group of friends when I was about 12 years old. I was the only non-citizen and the only one to pass. I’m drawn to the complexity of the law and I recognize that this complexity can make it easier for those who don’t understand it to be harmed by it.

My interest in economics began in community college, specifically in a microeconomics class taught by the wonderful Dr. Shruti Sharma. Having worked in an international agricultural industry and participated in the labor force, I realized how important the work of economists is. Economics isn’t merely a theoretical subject; the research economists do informs decisions that have a global impact. Therefore, it’s important for economists to reflect the world we live in!

Higher education is increasingly out of reach for those not born to privilege, especially first-gen students and student-parents, who, due to child-care costs, often pay more per year than their peers without children. What, if any, financial challenges have you faced in your academic journey? And how are you paying for college and the costs of attendance beyond tuition?

Thankfully, my tuition at Princeton is fully covered by university grants, which include room and board. That has helped to defray costs beyond tuition. Even still, as a parent of three, child-care costs are my biggest financial challenge. I mentioned earlier that choosing to return to college was an incredibly hard decision — largely because I felt that it was selfish to do so as a working mother. Living in NYC is expensive, and, at the time, we were a two-income family. I feared there was no way I could go to school full time and excel, which was important to me. The guilt I felt about wanting to stay in school was unbearable. Thankfully, my husband is supportive of my educational goals and assured me that he’d do whatever it takes to help make my higher education dreams a reality.

Research has shown that student-parents often face other unique challenges, including significant time constraints and not feeling like they belong. What hurdles have you encountered and how have you overcome them?

When talking about student-parents, it’s essential to disaggregate student-mothers. Take my own case, for example. I’m grateful for my husband’s support, but he works in a field that’s predominantly male and presumes that everyone has “a wife” at home. When one of our kids is sick or when daycare or school closes, he’s not granted the same flexibility to take time off that I was when I was working without it affecting how he’s perceived at work. He’s also the only one working now, and if he doesn’t work, he doesn’t get paid. While the division of work in our own marriage is egalitarian, I still have to navigate a world that doesn’t value my goals, dreams, or concerns equally. I depend on my community of family and friends and crowdsource ideas and caregivers, as women have done since time immemorial. I’m lucky that my extended family supports my educational goals unfailingly and will always step in to help me with last-minute child care.

Now that I’ve transferred to Princeton, I’ve had to leave my family support behind, which has been difficult. I’m not only adjusting to the rigor of Princeton like every other undergraduate, but my entire family is also adjusting. My kids are in new schools, my husband has a new, much longer commute, and I’m balancing a lot more than I was previously. It’s worth it, but this is the reality of being a mother at an institution like Princeton. In the classroom, this often means having conversations with professors ahead of time about my home life and responsibilities, working ahead when I can, and arranging for extensions when I can’t.

When I was selecting schools to apply to, I had to keep my entire family in mind. Unlike students without children, I had to understand the early child-care landscape in the area surrounding my school and consider my husband’s career and what a move would mean for our family in terms of income and health insurance.

What tradeoffs have you and your family made?

When I was pregnant with my youngest, who is nearly a year old now, it took me longer to complete my schoolwork, and my husband knew my grades were important to me. He would start his day at 4:30 a.m. and work until it was time to put the kids to bed to give me the time that I needed.

These days, I do my best to keep 9-6 hours. I do all the mornings with the kids, and once they’re dropped off, I treat school like it’s my job. At Princeton, I struggled initially to find after-care for our eldest, and that was tough. I really depend on having that time, so I can be present with my family.

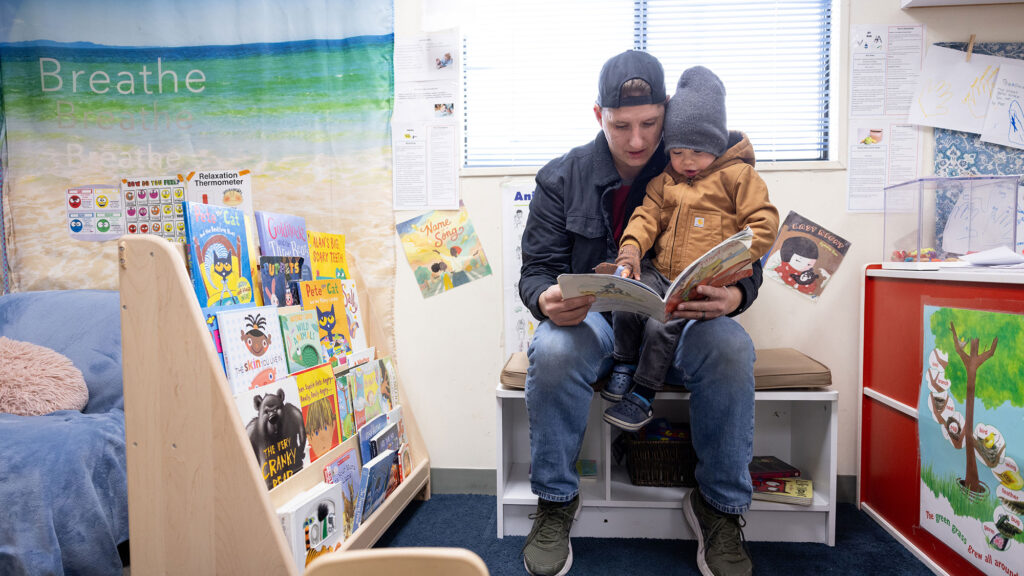

I’ve also learned to not let perfect be the enemy of good. I’d like to have 15 hours to commit to every assignment, but as I’m not a typical undergraduate student, I might only have eight. I need to triage, tend to what’s most important, and know when to shut my laptop. Sometimes, what I need is not to continue working, but to read my kids a story and give them a hug.

How did your time at Borough of Manhattan Community College ease your transition to Princeton?

My time there was incredible. My classes were small, I received personal attention from professors, and it was impossible for me to fall off the radar. I realized that I need that kind of experience as a student, and it partially explained why I struggled so much at my first school, which was a huge state university. I got comfortable being present, participating, and reaccustomed to the classroom in an extremely supportive environment.

Undoubtedly the best thing BMCC brought me was the Kaplan Leadership Program. Being selected as a Kaplan Leadership Program Scholar was quite literally life-changing for me. Here was a program that wouldn’t let me lose sight of my deadlines for essays or financial aid documents, that told me, “You can dream bigger than you are right now,” that didn’t let me lose sight of who I am and all I had to offer to selective institutions as a nontraditional-aged student and mother.

What advice would you offer to students and student-parents like yourself?

The most important thing I can offer to other nontraditional-aged students and student-parents is this: You have a lot to contribute to any higher education institution. Seek out schools that value students like us and put your best foot forward. I’ve met so many other inspiring student-parents on my journey and I’ve been able to find community. And don’t shy away from the traditional-aged students in your classes! They’ve enriched my experience in ways I didn’t expect!

An estimated 1 in 5 college students is a parent, but colleges weren’t designed with these students in mind. What can colleges and programs do to better support them?

In NYC, we benefited from an expanded child-care assistance program, which alleviated our concerns about child-care costs. Unfortunately, this is not true in every other state I applied to, except for California. When I got my first transfer application acceptance, I was hit hard by this fact. The excitement of feeling, “Yay, you’ve been accepted to this incredibly selective school!” quickly turned into a sinking feeling in my stomach about the lack of affordable early child-care education in the school’s area. Some schools offered discounts at their on-campus daycare for staff, but not for students. There are some amazing schools I was accepted to that don’t offer family housing, despite claiming that living on-campus is an integral part of the student experience. I understand that not all schools are designed to support students in my position, and they’re allowed to take that stance. But when schools recruit and accept nontraditional students, it’s incumbent on them to consider how to make the experience as welcoming as possible to us.

The amazing thing about the Kaplan Leadership Program is that the support you receive is tailored to who you are. I was the first Kaplan Leadership Program Scholar to give birth during the program — my youngest was just two months when I started filling out applications and writing essays, so I needed an accountability partner more than anything. Our amazing academic adviser, Jonathan Chavez, was that for me — making himself available at odd hours, knowing that I was up with a newborn. The program provides a cohort experience, which was invaluable to me. I had nine other scholars who were laser-focused on their goals, reminding me that my goals outside of motherhood were important too. Without KLP, I wouldn’t be at Princeton — not because I lacked the ability, but because without them, I lacked the vision. Sometimes it takes someone outside of yourself to see you clearly, which is especially true in the postpartum period when you can hardly remember who you are. My wish is for the Kaplan Educational Foundation to continue to be that for other scholars for generations to come.

Series: Getting To & Through College

Meet Tymika Lawrence, an immigrant and mother of three children under the age of 10. She recently earned an associate of arts degree from the CUNY Borough of Manhattan Community College before transferring, with support from the Kaplan Educational Foundation

Meet Tymika Lawrence, an immigrant and mother of three children under the age of 10. She recently earned an associate of arts degree from the CUNY Borough of Manhattan Community College before transferring, with support from the Kaplan Educational Foundation