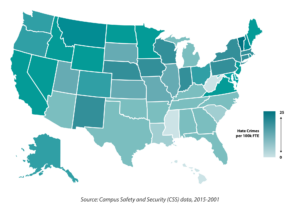

Vermont, whose institutions are primarily accredited by NECHE, had the highest rate of hate crimes per FTE at 25.32, followed by Washington D.C. (MSCHE) with a rate of 19.75, Rhode Island (NECHE) with a rate of 17.41, and New Hampshire (NECHE) with a rate of 17.34. In fact, all six of the states in which NECHE is the primary accreditor (VT, RI, NH, CT, MA, ME) rank in the top half for hate crimes per 100,000 FTE, with five of six ranking in the top 10. In contrast, all 10 states with SACSCOC as their primary accreditor (MS, VA, NC, KY, TN, AL, FL, GA, SC, LA) rank in the bottom half of hate crimes per 100,000 FTE. SACSCOC is also the primary accreditor for Mississippi, which has the lowest rate of hate crimes at 0.35 per 100,000 FTE. For more information, see Figure 6 here.

While there may not be an obvious correlation between states with significantly higher rates of reported hate crimes, one possible explanation is that students are less afraid to come forward and, thus, more likely to report crimes in states that have more protections, awareness, and accepting climates. Closer monitoring and collection of more and better data might also signal that hate crimes and campus climate are being taken seriously, which might lead more crime victims to come forward.

More investigation is needed to fully understand the impact of these crimes on student well-being, campus racial climate, and overall safety. By examining the experiences of under-represented students, higher education leaders and researchers can identify persistent patterns on campuses.

By addressing the issue of underreporting and enhancing campus safety measures, institutional leaders can improve the accuracy of hate crime data, better support victims, and create safer, more inclusive campuses.

How College Leaders Can Raise Awareness & Improve Campus Racial Climates

The implementation of the Clery Act — and some colleges’ failure to comply with it — only underscores the continuing need to ensure that colleges collect and share accurate campus crime data and use it to better understand what is happening on their campuses. Fostering positive racial climates on college campuses, addressing systemic issues, and ensuring student success and well-being is a crucial part of that, a recent report by EdTrust suggests. That report sheds light on the experiences of Black and Latino students — many of whom said they feel unwelcome and unsafe on their campuses — and highlights how a pervasive lack of diversity and adequate support structures for students of color can undermine trust in hate crime reporting systems.

Here are some things college and university leaders can do:

- Improve Campus Racial Climate

Colleges and universities should use campus climate surveys to regularly evaluate student perceptions and address negative views held by peers and faculty toward students of color via educational initiatives aimed at reducing racial and ethnic biases. These educational initiatives should be inclusive, so all campus community members — students, faculty, and staff — can learn to recognize and challenge the stereotypes and misconceptions they hold about individuals who differ from them.

- Enhance Awareness, Accessibility, and Accountability of Reporting Mechanisms

Institutions should ensure that students are clearly informed about federal requirements for reporting hate crimes, what constitutes a hate crime, and how to report one. This information should be clearly communicated to students throughout their time in college using multiple methods (e.g., emails, webinars, orientation sessions, flyers, etc.). Institutions should also ensure that students who report hate crimes will not face retaliation and will be supported throughout the process and have the option to remain anonymous, if desired. To achieve this, institutions may need to upgrade their data management systems and implement secure, user-friendly reporting platforms. Universities should regularly monitor and analyze this data to identify patterns, track the progress of reported incidents, and ensure that they are providing timely and appropriate responses, as well as regular hate crime statistics to the campus community.

How College Accreditors Can Reduce Hate Crimes & Boost Educational Quality

Accrediting agencies are responsible for supervising the policies, functions, and practices of higher education institutions. These agencies help hold colleges and universities accountable, alongside the federal government and state regulators. Colleges and universities must be accredited by a federally recognized agency to be eligible for federal dollars, including financial aid.

Despite these existing oversight mechanisms, the absence of explicit accrediting requirements related to campus racial climate, hate crime prevention, inclusion, belonging, and resources for victims of hate crimes is concerning. This gap raises questions about how institutions and accrediting agencies utilize the data they collect beyond mere reporting. There is little guidance on integrating this data into actionable policies that address and mitigate hate crimes. Without robust policies and accountability measures, institutions may fail to create safe and inclusive environments on campus.

While current standards require institutions to provide annual hate crime statistics to accreditors and the federal government, no accrediting body includes language in their accreditation policies on monitoring campus racial climate or hate crime statistics. This glaring oversight highlights the failure of universities and accreditors to address the pervasive issue of campus hate crimes.

Here are some things accreditors can do:

- Regularly Review & Monitor Hate Crime Trends

Accreditors should collect their own data on hate crime incidents and track trends across the institutions they accredit, so they can provide detailed guidance and support to institutions on best practices for hate crime prevention and response. Accreditors should regularly review annual hate crime data and institutional reporting mechanisms to identify hotspots and assess the effectiveness of reporting systems. They should also require universities to publish regular reports on hate crime statistics and measures taken to address them. Accreditation standards should explicitly include the collection, reporting, and addressing of hate crime data as a crucial element of institutional compliance.

- Hold Institutions Accountable

Accreditors can help ensure that institutions have a clear strategy for reducing crime on campus by incorporating specific accreditation requirements related to hate crime instances and reporting. Accreditors should meet with university leaders to discuss ongoing challenges and progress in addressing campus hate crimes and campus racial climate to help the universities they accredit remain on track and provide guidance when necessary. Accreditors should require institutions to implement proactive educational initiatives, comprehensive reporting protocols, and support systems to ensure that all students feel heard, safe, and respected on campus.

By actively engaging with institutions and maintaining a comprehensive data-driven approach, accreditors can help ensure that higher education institutions are not only compliant but also proactive in creating safe and inclusive campus environments.

How Policymakers Can Reduce Hate Crimes & Improve Campus Racial Climates

State and federal policymakers can play a significant role in improving campus racial climate and cultivating safer college campuses. The Clery Act was designed to protect and inform students by requiring institutions to be transparent about violent crimes on campus. However, several changes are needed to better protect students, especially traditionally under-represented students, who are more likely to be victims of hate crimes. Individual institutions and institutional accreditors can also do more to help to reduce hate crimes on campus. Here are a few of our ideas:

- Update the Clery Act to Improve Hate Crime Data Collection

Congress should update the Clery Act to require the disaggregation of hate crime data by race, ethnicity, and other factors. This will allow for a more accurate identification of at-risk groups and trends related to the underlying factors that drive hate crimes and the types of crimes being committed. Additionally, federal agencies can improve hate crime data management systems by not only gathering hate crime data but also making it readily available to relevant parties. With this information, universities can offer targeted support and protection to the most vulnerable student populations, fostering a safer and more inclusive educational environment.

- Provide Technical Assistance to Improve Data Management Systems

States and federal policymakers should provide technical assistance and resources to institutions to improve data reporting and accuracy. This support can help institutions modernize their reporting platforms to facilitate real-time incident reporting. User-friendly interfaces and mobile applications can encourage students and staff to promptly report incidents, ensuring that data is collected efficiently and effectively. These systems should prioritize data security and privacy, ensuring that sensitive information is protected while remaining accessible to those who need it. Additionally, policymakers should facilitate training programs for campus personnel on best practices for data management and reporting, ensuring that all staff are equipped to handle reports accurately and sensitively.

Conclusion

Hate crime prevention on campus is an evolving challenge. While much of the responsibility for hate crime prevention rightfully falls on individual institutions that are directly involved in their students’ everyday lives, institutional accreditors and policymakers can play a more significant role in preventing these crimes, protecting students, improving hate crime policies, and holding institutions accountable for responding to hate crimes. Accreditors should work with institutions to regularly update and review their data management practices, reporting mechanisms, and preventive measures, ensuring they remain effective and responsive to the latest developments in hate crime reporting and prevention. Better data collection, outreach, and dissemination at the institutional and federal levels would allow institutional leaders and policymakers to make better data-informed decisions about how to support all students, especially students of color and other traditionally under-represented students and might go a long way toward keeping these students safe.

Michael Grigsby is a doctoral student at the University of Southern California Rossier School of Education and a former research and data intern at EdTrust.