How College Application Fees Are Barriers to College Access

Being one of a few people in my family with a college degree, I am often called on to support family members, friends of the family, and even friends of…

Being one of a few people in my family with a college degree, I am often called on to support family members, friends of the family, and even friends of friends with the college application process every year. Rarely am I asked about college application fees — until months later, when prospective students are just about to submit their applications.

Research shows that waiving college application fees increases college matriculation (particularly for students at under-resourced high schools receiving college counseling) and induces high-achieving students from low-income backgrounds to apply and be admitted to more selective institutions. College application fees can even be obstacles for students from higher-income backgrounds.

Students don’t have to pay to apply for a scholarship or an internship. And they don’t have to pay to apply for a job. So why is it OK for students to pay to apply to college? It’s not. After going through yet another year of helping prospective students navigate the college application process and hearing the frustration and despair in their voices, I decided to express my own frustration about college application fees publicly via a tweet:

I did not expect the number of responses to my tweet. Their personal stories motivated this blog post.

College application fees are barriers to postsecondary access and flat out scams. pic.twitter.com/olrewMTh2i

— Marshall Anthony Jr., Ph.D. (@mcanthonyjr) October 24, 2019

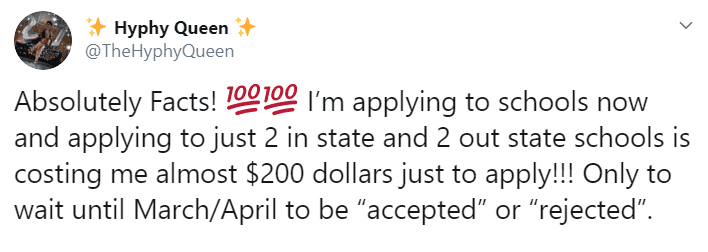

While application fees may be a drop in the bucket for college budgets, they can be a significant investment for students and their families, especially for students from low-income backgrounds. On average, college application fees are about $50 at most four-year, not-for-profit institutions, but they can go even higher: Among 61 four-year institutions with the highest application fees, the average fee is $77, with Stanford University requiring a $90 application fee. And hardly anyone just submits one application. Since fall 2013, more than 80% of first-time, first-year students submitted three or more college applications each year. Since fall 2014, almost 36% of first-year students applied to seven or more colleges, annually. Therefore, a student’s total application fee costs can quickly add up to about $150 after applying to at least three four-year, nonprofit institutions, and at least $540 if they apply to seven elite institutions.

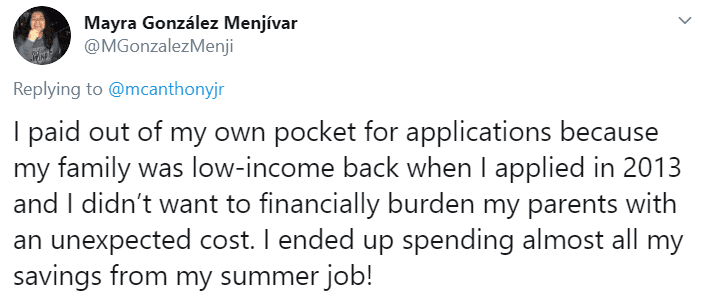

These fees are absolutely absurd, especially for students from low-income backgrounds. And if you think they can easily pay for these fees, ask Alexis, Mayra, Olivia, and Ya’Mese:

Well, what about fee waivers? In a recent blog post on Inside Higher Ed, Matt Reed writes, “Yes, there are fee waivers, but you have to know to ask, and the first message they communicate to the student is ‘prove you’re poor.’ That’s not a great first impression.”

Indeed. When I first applied to college 10 years ago, my status as a free or reduced-price lunch (FRPL) recipient determined whether I received fee waivers. But the only reason why I received FRPL is because my mother completed the necessary paperwork. But what about parents or guardians who are unaware of FRPL? For those who know it exists, what if they don’t have time to complete the paperwork? We cannot assume that all students who most likely qualify for FRPL actually receive it. In fact, research indicates that FRPL is not always the best proxy for students from low-income backgrounds.

Luckily, my high school guidance counselor, Ms. Long, knew I came from a low-income background. And let me tell you it is not easy telling others that information — it is a vulnerable act of self-disclosure. But because Ms. Long checked in with me consistently throughout high school, I felt comfortable sharing that information with her. Unfortunately, considering the shortage of guidance counselors nationwide (and their workload), many students don’t have access to a reliable counselor, especially students from low-income backgrounds and students of color. Oftentimes, guidance counselors (or similar authority figures) are gatekeepers to fee waivers and/or income verification. So if a student doesn’t have a strong relationship with their guidance counselor or if the average student-to-guidance counselor ratio is bad (which is 464:1 nationally), a student may not realize that fee waivers are available until it is too late to qualify for them. Additionally, for the growing demographic of non-traditional aged prospective students who graduated from high school years before going to college, how are they supposed to find out about application fee waivers without a guidance counselor?

There is only one obvious solution to college application fees: eliminate them. Some places are already making efforts to do so, but those efforts still fall short. For example, each year, the College Foundation of North Carolina hosts College Application Week. During this week, a number of public and private institutions offer application fee waivers. However, not every college participates, including some of the most prominent ones in the state, NC State and UNC. Efforts to eliminate college application fees are not promising in California either. Last July, California State University trustees raised the application fee for each of the system’s 23 campuses from $55 to $70. This is just unacceptable.

College application fees are unnecessary and costly burdens for students from low-income backgrounds. Moreover, we cannot guarantee that the students who need fee waivers the most are receiving information about them in a timely manner, if at all. Today, nearly two-thirds of all jobs in the U.S. require some form of postsecondary education. Therefore, we should be making it easier for prospective students to access college. But application fees do the exact opposite — they make it harder for all students to obtain a necessary postsecondary education. Similar to race-neutral and legacy admission, the use of college application fees is yet another inequitable admissions practice that has gone too far for too long.