When we think about collateral consequences of mass incarceration, what are your immediate thoughts? Imagine being incarcerated for 26 years and learning to navigate through having computer literacy, finding mentors, and connecting to people in educational and work systems who have empathy for what you have been through, all while reacclimating to life outside of a Georgia prison. That was my experience.

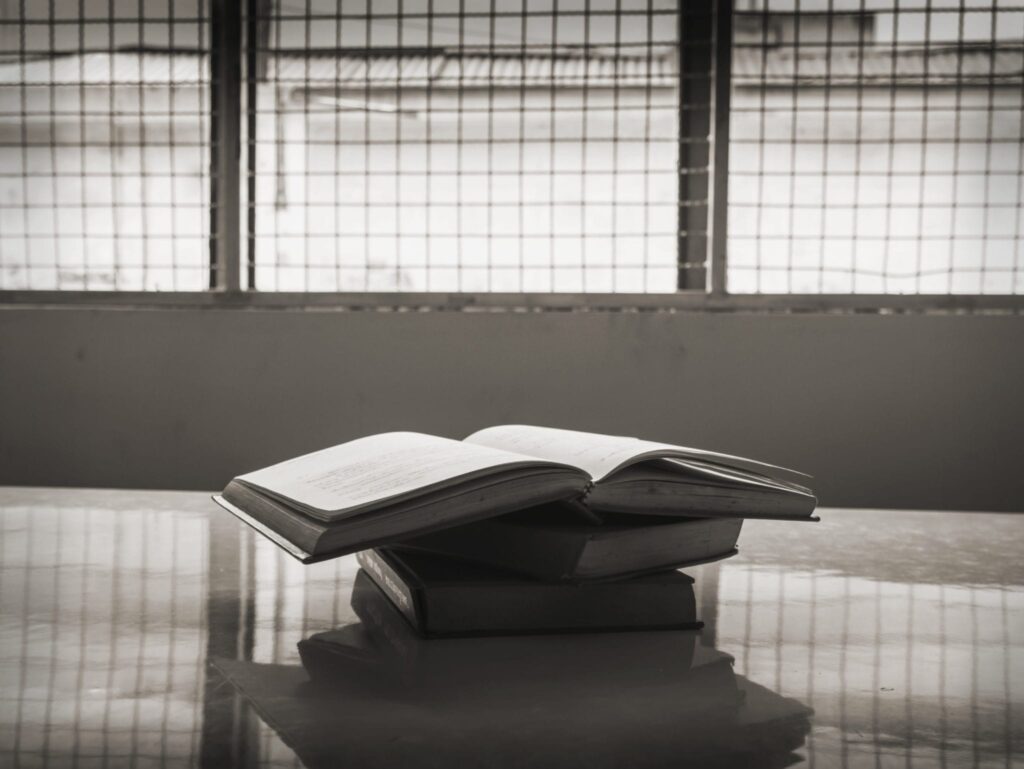

I found that due to limited access to technology, there was no way for me to prepare for modern usage of computers and the internet. After 26 years, technology had evolved and I needed to catch up to be equipped with the hard skills necessary for any job, and moreover, my career. Even though I completed all the requisite coursework and earned certifications, there was little consideration for applying my knowledge to real world.

For example, I was unaware of how to apply for college admissions and student financial assistance with the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) upon release. Ultimately. I was awarded a full scholarship through the Chillon Project. My tuition and education associated costs were covered. FAFSA created a pathway to student work study access, which provided financial stability. While the studentaid.gov website promotes the FAFSA form as a free and straightforward process, the reality involves navigating multiple passwords, understanding household income details, and accessing tax history, leads to mounting frustrations for first-generation students, Black and Latino students, and even people who haven’t been incarcerated. The difficulty for people like me is even more heightened, and with few options for assistance in filling out the forms it can seem hopeless.

By providing mentorship, guidance, resources, and a supportive environment, college faculty and staff can empower directly impacted students, giving them the opportunity to thrive in college and beyond. It is through these efforts that we can create a more inclusive and equitable educational system that values the potential and resilience of all students, regardless of their life circumstances. The implementation of academia and a touch of empathy helps higher ed students and faculty work towards a more inclusive and equitable system that empowers all students to succeed, regardless of their life circumstances. This not only benefits the individual students, but it also leads to a more diverse and skilled workforce, which ultimately benefits society and the U.S. economy writ large.

My academic mentors affirmed me as a college student and became a necessary component to successful reentry. There were times when I doubted my ability to complete a course without dropping mid-quarter, in fear of not being able to maintain my required GPA. University faculty and staff have been instrumental and pivotal. These relationships were vital to successful reentry. Surrounding oneself with people who know where you came from and can see your growth is imperative. These kinds of mentors can help an individual identify who they are and in which direction their lives are headed. I was invested in my education during my incarceration. My innovative and exceptional leadership encouraged me and my peers to persevere. So, it’s also important to find support from people with similar lived experiences or support systems who have empathy for an individual returning into the community to make the expectations and pathway to education easier.

This frustration is only compounded by my recent release back into the community. The cultivation of trauma informed approach is described as a program that has the component of compassion and empathy for a justice-impacted student built in. There is the holistic perspective in which an individual who is impacted by the justice system must have a safe place to process their trauma, and sometimes, that place is the system of academia.

In conclusion, education creates a pathway to reintegration back into community. It gives a justice-impacted individual a clear vision of what a higher quality of life can look like. Supporting directly impacted students through the college application process is the key to ensure equitable access to higher education. By recognizing and addressing the unique challenges formerly incarcerated people face, we can help these students overcome obstacles and pursue their academic dreams. This can look like assisting with online applications, transportation or driving lessons, medical care, housing, employment or even learning how to do simple things like making an appointment or ordering books — because what most people take for granted can be brand new to the formerly incarcerated.

Kareemah Hanifa is a community organizer with the Inner-City Muslim Action Network, a student at Life University in the Positive Psychology master program, and an EdTrust Justice Fellow.