Math as Play: Cultivating a Nation of Math People

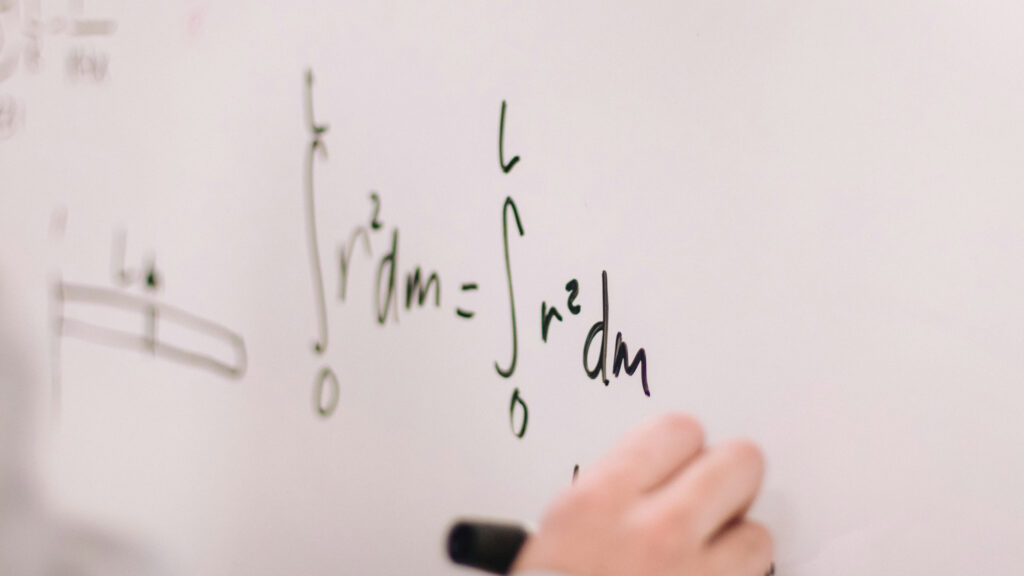

Math can involve numbers, but mathematics is so much more than digits strung together by symbols

When someone asks me where I’m from, I often shrug and admit I don’t know how to answer.

As both an immigrant and the daughter of medical missionaries, I lived in four countries by the time I was 16. “Home” was a bit nebulous for me.

While I’m grateful for my culturally rich upbringing, I didn’t always see the benefits of moving from continent to continent as a child. Every time we moved, I had to learn new cultural norms. Every time we moved, the language changed, the food changed, the climate changed, the expectations changed.

But no matter if I was in Uppsala, Sweden; Almaty, Kazakhstan; Tulsa, Oklahoma; or Dushanbe, Tajikistan, there were always…

60 seconds in a minute…

60 minutes in an hour…

24 hours in a day.

Numbers were my constant. They were my companion. They are universal and transcendental: when everything around me changed, numbers became my security blanket.

Oftentimes, the only recognizable symbols were numbers.

I have my dad to thank for this. When other parents were reading their kids bedtime stories, my dad would ask me questions like, “How would you estimate the sales tax on this purchase?” or “What’s another way you could find the product of those two numbers?”

To my dad, and hence to me, math was play. And since math was my constant, I learned I could play math everywhere. Sure, math can involve numbers, but mathematics is so much more than digits strung together by symbols. Math is problem-solving, puzzling, and predicting. Math is collaborating, communicating, and creating. And yet, our country is full of adults and students alike who would quickly say they are not “math people.”

I am by no means the first to point this out, but there’s a bit of academic hypocrisy here because Americans, generally, would not say, “I don’t know how to read.” Yet, I’ve met many people who have told me, “I just don’t do math.” Our cultural acceptance of not being “math people” is not shared by other cultures across the globe. So, the question we need to wrestle with is: how do we foster the next generation of mathematical thinkers?

Certainly, we can look to the work our own nation has done in reading. While the world is out-preforming us in mathematics, we are out-performing them in reading. First, we are committed to reading to our children early. As a new mom, I was often told, “Talking is teaching.” I was pointed to research that said kids who read, or are read to, for 20 minutes a day are exposed to 1.8 million words in a school year, as compared to students who read 5 minutes a day and are exposed to 282,000 words per year.

There is no question about the importance of integrating reading into our daily rhythms.

However, I don’t see the same importance placed on early numeracy as I do early literacy. Just like we tell new parents that “talking is teaching” and just like we encourage them to read, read, read to their young ones, so we can tell them that “math is play.” We should help parents see that math is all around us: point out the shapes you see on that building (geometry); play a guessing game (number theory); challenge your kid to a card game (statistics); or ask them to generalize a pattern (algebra). We have math opportunities with our kids all around us, every day, because we have play opportunities all around us.

Additionally, my English teacher friends have taught me the importance of autonomy for our students in finding their identity as readers. When a student tells an English teacher, “I don’t really like to read,” the teacher most likely will respond with: “We just haven’t found you the right book yet!” What if, when our students said, “I don’t really like math,” we were able to respond with: “We just haven’t found you the right problem yet.”

One barrier to this lies with our high school mathematics curricula and requirements. Most students are asked to master objectives like solving logarithmic equations, graphing rational functions, and identifying conic sections in order to graduate from high school in America. It’s no wonder math teachers are often confronted with, “When am I ever going to use this?” The truth is: most students won’t use this. And yet we force so many students — and teachers — into this one pathway.

It’s a bit like saying the only way to be a reader is to read Shakespeare. And only Shakespeare. The only way to be a mathematician is not solely through algebra. Although we must ensure more students have access to these traditional pathways, we also must ensure a broader array of options.

If we want to foster mathematical thinkers, we must foster a love of math. And to foster a love of math, we need to play with numbers, theories, and logic based in the real-world early on and then let our students have more options in their mathematical education. In order to cultivate a nation of “math people,” we must foster joy and wonder in the subject early on and then continue to grow it through autonomy and choice.

Rebecka Peterson is a high school math teacher in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and the 2023 National Teacher of the Year.