Recommitting to the Civil Rights Legacy of ESEA

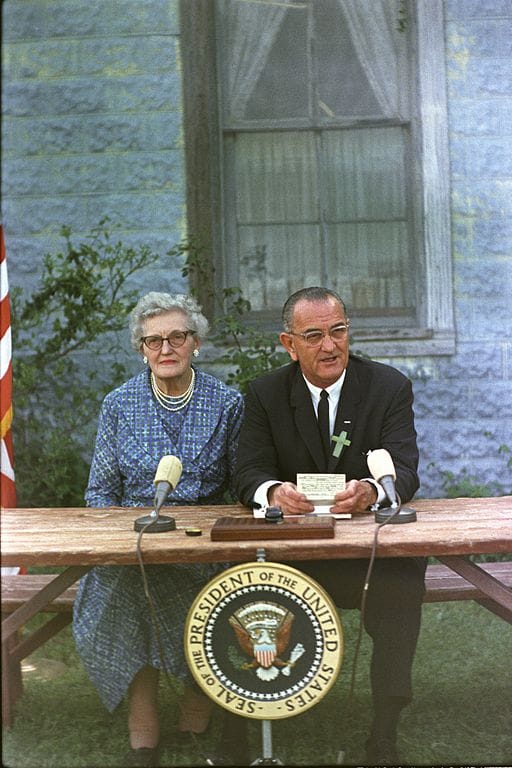

On this day 52 years ago, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Elementary and Secondary Education Act into law. With his elementary school teacher, Katie Deadrich, by his side and…

On this day 52 years ago, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Elementary and Secondary Education Act into law. With his elementary school teacher, Katie Deadrich, by his side and with the one-room schoolhouse he attended as a child as a backdrop, Johnson proclaimed that no law he ever signed would mean more to the future of America than ESEA.

When the law passed, Johnson declared, “[ESEA] represents a major new commitment of the federal government to quality and equality in the schooling that we offer our young people.” As the son of a tenant farmer and as a former classroom teacher in rural Cotulla, Texas, Johnson saw firsthand education’s power as the “only valid passport out of poverty” and its importance in transforming lives and increasing equity.

ESEA marked a historic step for education, as well as for civil rights. Indeed, educational opportunity and civil rights always have been intertwined, and they remain so today.

Since its passage in 1965, ESEA helped establish the expectation that a child’s ZIP code, race, family income, background, home language, or disability should never be a barrier to a quality education. The law also helped historically underserved children receive the resources they need, so that the promise of America — as a country in which our people can become whatever they dream — can be a reality for all.

Over the years, as a nation, we have made great progress in education. Our high school graduation rate is at its highest point in history. Dropout rates are at record lows. More students — especially African American and Latino students — are enrolling in college than ever before. There are other indicators, too, that point to improvements over the last half-century — including increased access to early childhood education and advances in technology that help personalize learning to students’ unique needs and interests.

Yet crucial work remains. Unacceptable opportunity gaps persist in America. Students of color, particularly African American students, and students with disabilities face harsher discipline and a larger number of suspensions and expulsions beginning as early as preschool. In far too many schools, we continue to offer our most vulnerable students less — including less access to challenging coursework, effective teachers, school counselors, and other supports necessary for them to thrive in college, careers, and life.

I remain hopeful, though, that as a nation, we are positioned to make necessary progress because of the Every Student Succeeds Act, which reauthorizes ESEA. The new law seeks to build on the civil rights heritage of the original ESEA by extending the promise of a rich, well-rounded education to every student regardless of race, family income, home language, disability, or any other circumstance.

But a lot depends on the new law’s implementation.

ESSA provides the opportunity for states, local districts, and educators to leverage flexibilities in the law to increase innovation in education, expand opportunity, build on best practices to spur student growth and achievement, and consider the unique contexts of local schools.

But all of us — as educators, school and community leaders, parents, policymakers, and advocates — must demand that ESSA’s implementation results in the protection of every child’s right to a quality education and the support of all students. And all means all.

We cannot allow the promise of ESSA to be undermined by troubling recent developments on the federal policy landscape.

Last month, Congress voted to overturn the Obama administration’s regulations that clarified accountability, state plan, and public reporting provisions in ESSA. The regulations reinforced some of the law’s critical equity levers, such as the prioritization of academic outcomes and attention to key resources, such as transparency on education funding through per-pupil expenditures.

I’ve heard some say that the loss of the regulations means that states can do whatever they want to do. That’s simply not true. ESSA was not overturned. States still must comply both with the letter and the intent of the law.

The U.S. Department of Education seems to be signaling that it will take a hands-off approach when it comes to implementing ESSA, which means it’s up to each of us — educators, advocates, the civil rights community, parents and families, state and district policymakers, and everyone who cares about our kids — to make sure that all students — especially our most vulnerable — remain a primary focus in the law’s implementation.

On this 52nd anniversary of the signing of ESEA, let us recommit to our responsibility and moral obligation to honor the civil rights legacy of that law. Only then will we close opportunity and achievement gaps, ensure all children reach their potential, reduce economic and social inequalities, increase upward mobility, and fulfill our country’s promise.

Photo credit: Frank Wolfe via Wikimedia Commons