Social Justice in Mathematics

Too often, mathematics classrooms are governed by rigid, Eurocentric practices that overwhelm students

In 1990, KRS-One of Boogie Down Productions released Blackman in Effect, a powerful critique of the systemic inequities woven into the fabric of American society, including education. More than three decades later, many of the outdated structures he decried remain embedded in our schools. Our educational systems, especially in mathematics, often reflect values and assumptions shaped during a time when only white American men had access to formal learning. These norms, centered around memorization, silent compliance, and a narrow cultural lens continue to shape what we teach and how we teach it.

Too often, mathematics classrooms are governed by rigid, Eurocentric practices that overwhelm students with lecture, show and tell, and computational drill and skill techniques. These practices overlook the potential contributions of the students, their backgrounds, their experiences, and their interests. They limit opportunities for students to make sense of problems, reason abstractly, look for and use structures or repeated reasoning, or model with mathematics. Instead, many observed practices rely on songs, acronyms, and number tricks, that teach students that solving a problem is more important than understanding how to problem solve. SOHCAHTOA seemed like a great way to help students understand Trigonometry relationships until students repeatedly asked me how to spell it. That’s when I realized that it was not working.

Those same students could care less about my dear aunt Sally or the dumb cat that King Henry drove mad. That last one stood for Kilo, Hecto, Deka, Meter, Deci, Centi, Milli, in case you also forgot. Learners require meaningful connections and experiences to create mental building blocks that lead to content acquisition, application, and long-term retention. Memorization does not lead to fluency. Making sense of experiences through observations, connections, and inferences leads to fluency; flexible, efficient, and effective problem solving.

Educators, schools, and policymakers must understand that our students are often much more advanced than the credit given to them. Low expectations obscure the rich backgrounds and lived experiences of students, overlooking the opportunity to create meaningful connections to the content. Most teachers may not recognize that their expectations are low, but if you have ever said, “my students can’t…,” then it is time to start training your mind to recognize what they can do. What related concepts do they know? What connections can be made to those concepts? What experiences can they engage in to build awareness, relevance, and understanding that can lead them to recognizing and formalizing new mathematical ideas? A Calculus student may not know anything about derivatives or antiderivatives, but they may have some experience with the phenomenon of getting consistently closer to something that they cannot actually touch. Instruction must evolve so that students learn to be innovative mathematical thinkers.

At the core of every instructional program should be the development of activists; molding citizens who have the desire and ability to revolutionize. As educators, it is our responsibility to dismantle the practices, curricula, and policies that either restrain divergent thinking or limit students to thoughtlessly mimicking the ideas of others. We should instead encourage students to Widen their Options through Knowledge and Empowerment.

Widen options by developing intellectual traits that help them apply mathematics as a tool for strategically thinking through complex problems. My teaching focuses students on applying intellectual standards such as depth, clarity, relevance, and logic to elements of reasoning such as questioning, purpose, assumptions, and implications by making connections between content and context to expose students to multiple viewpoints and encouraging inquisition. A quality education equips students with the habits of mind that lead to wider personal, social, economic, and professional options. It provides a sense of empowerment that is fueled by knowledge. It challenges students to think deeply and critically about the world, emerging empowered to make informed decisions and incite positive societal change.

A mathematics classroom focused solely on facts and procedures stands in direct opposition to my style of teaching. For example, learning the Bill of Rights becomes meaningful when students analyze it and apply its meaning towards defending, advocating, or informing decisions. Similarly, solving an equation or calculating a percentage only matters when students can use these tools to navigate the real world.

What does this look like in practice? Consider these essential, everyday questions:

Answering these questions requires more than what is currently expected of our nation’s students. It demands mathematical literacy, the ability to read, write, reason, and apply mathematics in real contexts. This kind of literacy goes beyond decoding a text and goes far beyond having access to advanced math courses like calculus. This kind of literacy empowers students with the tools to navigate life, evaluate systems, and imagine new possibilities.

Unfortunately, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) reveals that we are far from achieving this vision. Since 2005, fewer than 26% of 12th graders have reached proficiency in math and in 2024, only 29% of students met College Readiness Benchmarks. This represents a crisis that affects our democracy, economy, and future. If our students can’t reason quantitatively or think critically, how can they hold leaders accountable or make informed choices that shape their communities?

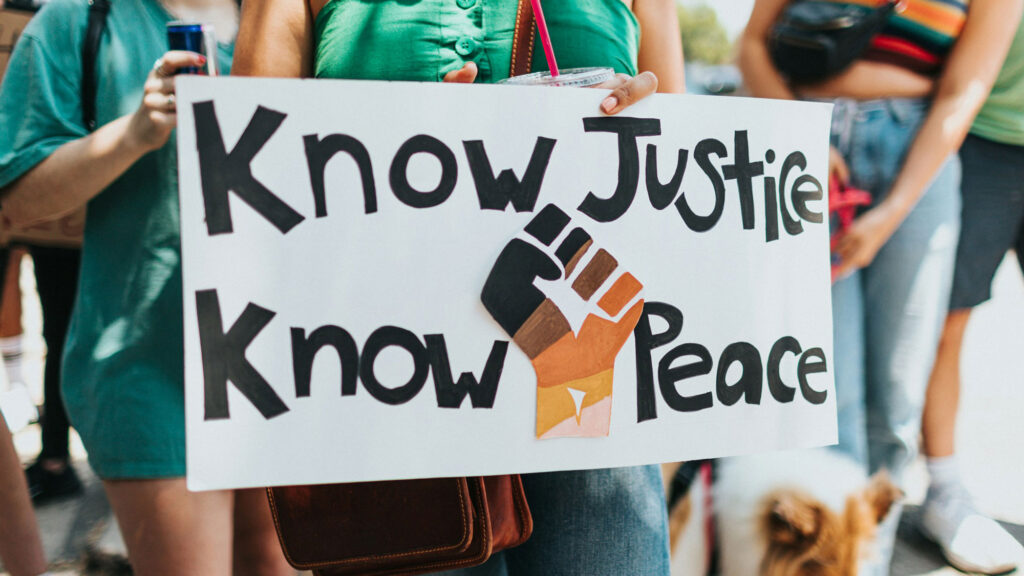

To change this, we must reimagine math instruction; not as a neutral collection of skills, but as a powerful tool for understanding and transforming the world. Social justice mathematics moves us toward that goal. Teaching mathematics for social justice utilizes mathematics to explore real-world issues and helps students understand the world around them. It allows them to investigate what matters most to them and to use mathematics to pursue answers and advocate for solutions.

For example, students might analyze school district funding patterns to understand educational inequity, or map pollution data in their neighborhoods to advocate for environmental justice. These investigations give math purpose. They foster curiosity. They build confidence. They allow students to move beyond being mere keepers of knowledge to becoming doers, citizens who use math to create impact.

Teaching mathematics through a lens of social justice isn’t an optional innovation. It’s a moral imperative. The next generation will only be capable of navigating complex issues, challenging injustice, and shaping a better world if they are taught math that matters. Math that tells the truth. Math that empowers. Math that revolutionizes.

Let’s prepare our students not just to solve problems but to question, connect, and create.

Photo by Nathan Dumlao on Unsplash