Who Receives TRIO Funding? A National Snapshot of Federal TRIO Funding at Colleges and Universities

An overview of which colleges receive TRIO grants, the amounts of those awards, and how the funds are distributed

As a first-generation, low-income college student who attended a six-week pre-college program the summer before my freshman year, I know how incredibly impactful college-access programs can be. College-access programs generally support students with academic tutoring, admissions applications, and navigating financial aid. They provide academic advising, financial literacy support, and more to students who wouldn’t otherwise have access to those resources. That’s why I spent the past year analyzing national data on TRIO’s three college-access programs — Talent Search, Upward Bound, and Upward Bound Math and Science — as part of my graduate capstone project. Little did I imagine that in the middle of my project, TRIO funding would be frozen by the Trump administration. (But more on that later.)

My research focused on which colleges received grants, the size of those awards, and how funding was distributed based on five institutional characteristics, including size, location, and control (public or private). I combined key data using program grant awards from the Department of Education, institutional data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), and data on minority-serving institutions (MSIs) from the College Scorecard.

This work builds on a relatively limited body of national-level research. Only five nationwide analyses of TRIO programs have been conducted since 2000. The most recent was a 2009 study of Upward Bound by Mathematica Policy Research. Since then, most research on these programs has been local or site-specific, leaving a major gap in our understanding of how these efforts function at scale.

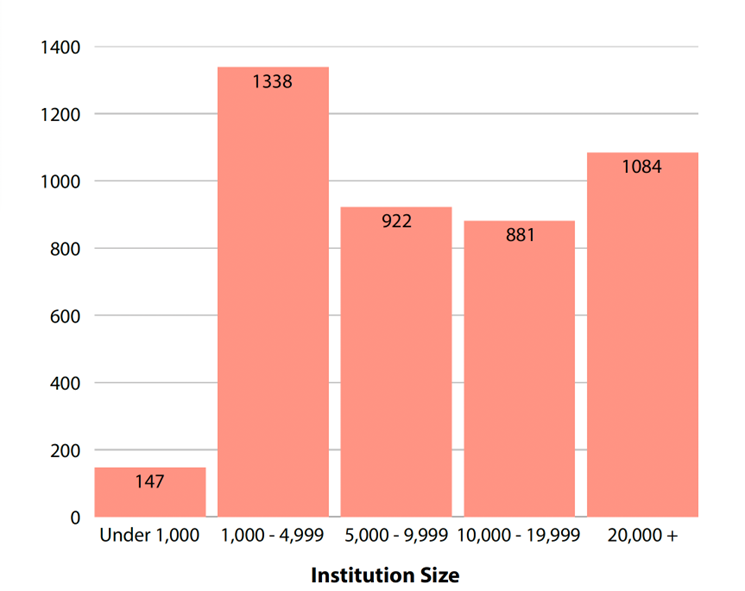

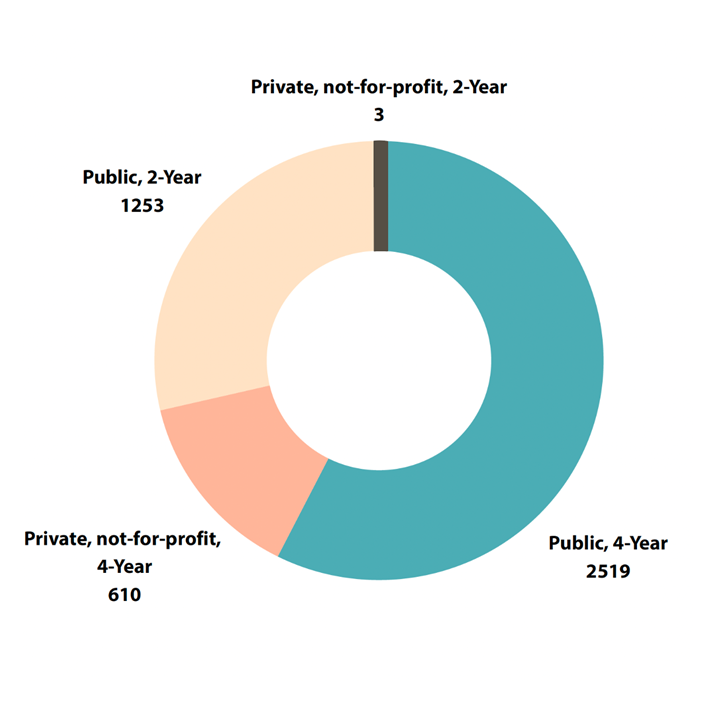

Most grantee institutions have small enrollments between 1,000 and 4,999 students and are in cities. The majority are also public colleges (89%). While MSIs are similarly concentrated in urban areas, they typically serve much larger student populations, often exceeding 20,000 students.

Figure 1: Number of grant awards by size of institution (AY 2021-24)

Source: Analysis of Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (FY2022-23) and ED Program Grant Awards (FY2021-24), https://www.ed.gov/grants-and-programs/grants-higher-education/federal-trio-programs.

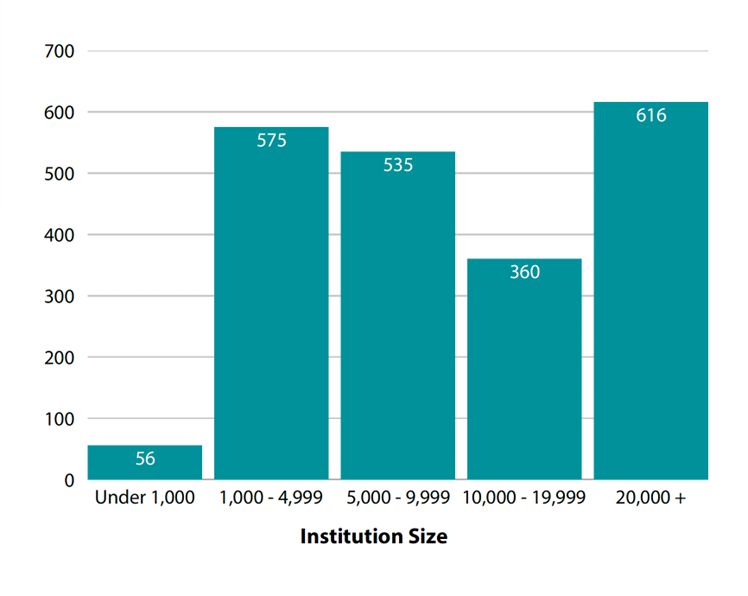

Figure 2: Number of grant awards by size of MSIs (AY 2021-24)

Source: Analysis of Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (FY2022-23) and ED Program Grant Awards (FY2021-24) , https://www.ed.gov/grants-and-programs/grants-higher-education/federal-trio-programs.

The overlap between TRIO grantees and minority-serving institutions (MSIs) is particularly noteworthy (see Figure 2).

Because MSIs, by definition, enroll high proportions of students of color and often have significant numbers of first-generation college students, their presence in the TRIO grantee pool shows that funds are reaching institutions that serve many of the students the program was designed to support. This alignment indicates that TRIO funding may be amplifying resources at schools that play a crucial role in advancing equity in higher education.

Figure 3: Number of grant awards by institutional sector (AY 2021-24)

Source: Analysis of Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (FY2022-23) and ED Program Grant Awards (FY2021-24), https://www.ed.gov/grants-and-programs/grants-higher-education/federal-trio-programs.

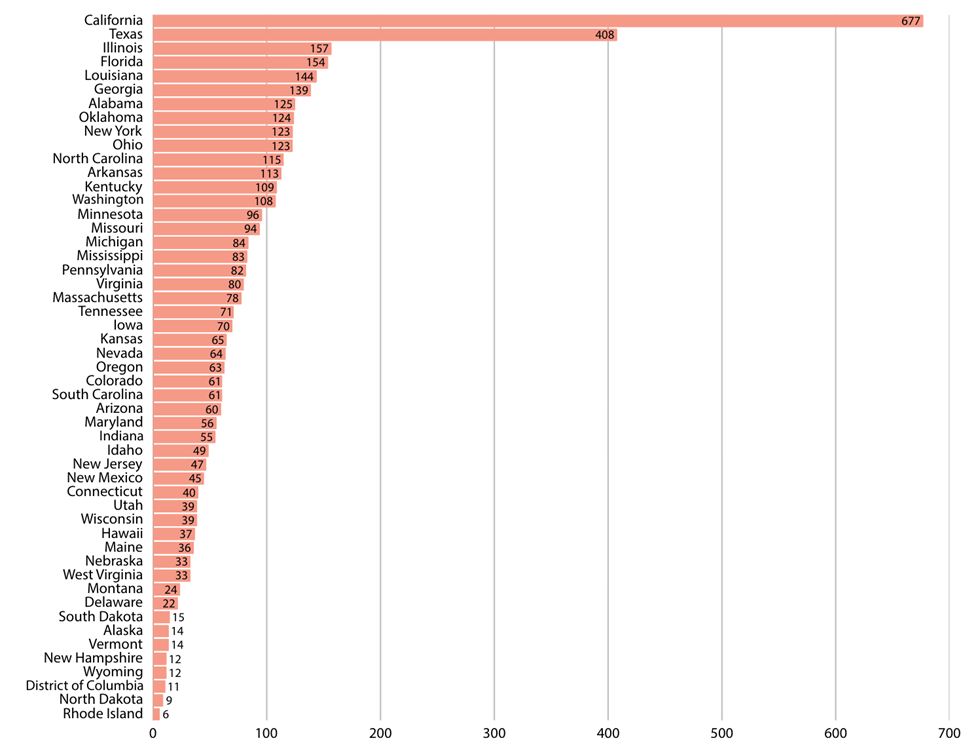

Figure 4: Number of grant awards per state (AY 2021-24)

Source: Analysis of Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (FY2022-23) and ED Program Grant Awards (FY2021-24), https://www.ed.gov/grants-and-programs/grants-higher-education/federal-trio-programs.

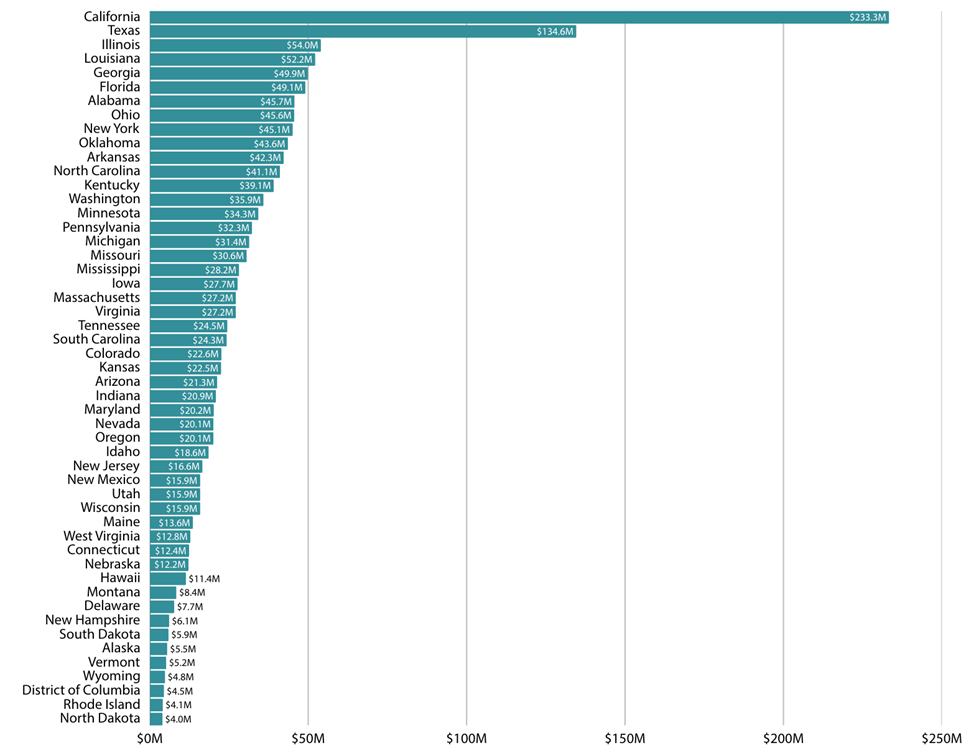

Figure 5: Grant funding per state (AY 2021-24)

Source: Analysis of Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (FY2022-23) and ED Program Grant Awards (FY2021-24), https://www.ed.gov/grants-and-programs/grants-higher-education/federal-trio-programs.

Between 2021-2024, California had the largest number of TRIO grant awards, with 677 totaling over $233 million (see Figures 4 and 5). Texas had 408 awards amounting to $132.7 million, and Florida, Illinois, and Georgia each recorded more than 130 awards and around $50 million in funding. States such as Vermont, Rhode Island, and North Dakota received fewer than 15 awards and less than $5 million. These differences reflect, in part, the size and number of eligible institutions in each state, as well as the concentration of colleges that meet TRIO’s target population criteria. For example, many Hispanic-serving institutions are concentrated in states like California, Texas, and Florida, which have large Latino populations, while many historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) and predominantly Black institutions (PBIs) are in Southern states with large Black populations. Overall, the distribution of awards and funding underscores how TRIO resources are spread across diverse higher education systems and student populations nationwide.

Additional research is needed to improve our collective understanding of how federally funded college-access programs function and their impact. Analyzing other federal initiatives, such as GEAR UP, could help us compare how different programs support students and where gaps remain.

More qualitative research that centers on the lived experiences of students is needed, too. Focus groups or interviews with former program participants could shed light on the nonacademic supports — such as mentorship and mental health services — that are often crucial to student success but overlooked in the data.

Finally, the Department of Education should release more data on these programs, and newly available public data should be used to explore what’s working and what needs to be changed. Future research should focus on which strategies lead to real outcomes, especially for first-generation and low-income students who face the greatest barriers.

While completing this capstone project, I witnessed firsthand how politics are increasingly undermining the traditional role and priorities of the Department of Education. Recently, the Trump administration withheld $660 million of the $1.2 billion in funding from several TRIO programs that support students from low-income backgrounds. However, federal support for these grant programs hasn’t completely vanished, as some awards have since been released and congressional lawmakers are working on legislation to maintain funding for many of the programs affected by the decision to freeze or cancel various grants. Still, the administration’s actions threaten the stability of programs that over 650,000 students depend on each year to pursue a higher education — a pathway that remains one of the most effective drivers of social mobility. It’s essential to preserve and strengthen these programs through ongoing evaluation and public accountability.

My analysis provides a national snapshot of TRIO funding distribution across public and not-for-profit private colleges and universities. Specifically, this research examines both the number of awards and the total dollars allocated, allowing us to understand which institutions receive grants and how these resources are distributed among different types of higher education institutions. By mapping this distribution, the analysis reveals investment patterns and highlights disparities in the federal support available to students based on where they are enrolled.

However, this inquiry does not address what impact these programs have on students. To evaluate program effectiveness, researchers and federal agencies will need more comprehensive data.

Going forward, federal agencies should take the following steps:

Pinpointing which interventions work best could strengthen program design, inform better practices, and help ensure that students receive the support they need to succeed. This project offered a glimpse of where TRIO funding goes but there is still more we need to understand.

TRIO programs exist to expand college opportunity for first-generation and low-income students like me. That mission remains just as important today, but with better data, smarter research, and real transparency, we can make sure TRIO lives up to its full potential and reaches every student it was meant to serve.

For more information on the distribution of TRIO funds, please see the dashboard.

Daniel Ceva recently earned a master’s degree in public administration from the University of Pennsylvania. The research highlighted in this blog is from his capstone project.

As part of our commitment to elevating diverse perspectives, EdTrust occasionally features guest blogs. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect EdTrust’s views or positions.

Photo by Allison Shelley/Complete College Photo Library