To mark the 65th anniversary of the Brown versus Board of Education ruling, Ed Trust created a special edition of ExtraOrdinary Districts.

On this web page you will find links to the archival audio we used as part of the podcast as well as additional resources.

CORRECTION: Please note that Walter Kee is incorrectly identified in the podcast as Delaware’s former secretary of education. He is the former secretary of agriculture. We apologize for the error.

Additional Resources

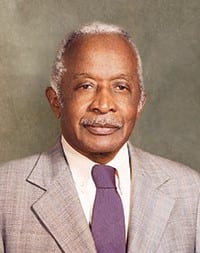

(photo courtesy of the University of Delaware)

“I was keenly aware that many Negroes themselves wanted to see a closer conformity in this country between the ideals expressed in our historic documents, such as the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, and practice with respect to Negroes. I say, I knew that Negroes wanted to see a coalescing of ideal with practice.”

– Louis L. Redding

The Special Collections of the University of Delaware houses an interview with Louis L. Redding as part of a project on the Great Depression. It can be found here.

(photo courtesy of the Library of Congress)

“We first started off to make the schools equal on the theory – and this was Margold’s theory – that if you made them so expensive they couldn’t maintain them, that segregation would die of its own weight. Well, eventually we found it wasn’t working, so then we shifted to hitting it straight on.”

– Thurgood Marshall

Thurgood Marshall, along with Charles Hamilton Houston and Nate Margold, developed a legal strategy to dismantle the doctrine of “separate but equal,” the legal loophole to the 14th Amendment devised by White supremacists after Reconstruction. Separate but equal was endorsed by the U.S. Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 and four other decisions. They began with university graduate programs and succeeded in gaining the admittance of Heman Sweatt to the University of Texas Law School in 1950 (Sweatt v. Painter).

NAACP Legal Defense Counsel Thurgood Marshall in front of Supreme Court

The interview used is part of the Columbia University Oral History Project.

Reminiscences of Thurgood Marshall (1977), Oral History, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

(photo courtesy of Delaware State University)

Delaware State College (now university) was founded in 1891 by the Delaware General Assembly as a segregated institution for Black Delawareans.

It had been underfunded for decades and in 1949 it lost its accreditation. Students turned to Louis L. Redding for help. Redding filed suit, asking that the all-White University of Delaware be compelled to admit African American students.

The case went before Collins Seitz, who had recently been appointed to the Delaware’s Court of Chancery, the only court in Delaware which can issue injunctions.

The case went before Collins Seitz, who had recently been appointed to the Delaware’s Court of Chancery, the only court in Delaware which can issue injunctions.

Seitz toured both the University of Delaware and Delaware State College and found “gross” disparities. He said that since the state had not maintained equal facilities, they could no longer be separate.

“I never went to school with a Black. Anywhere. So it wasn’t at the forefront of my mind at all. Wilmington High School was all White. So was the University. Virginia Law School. They were all White. So it wasn’t one of those problems I had occasion to think about.”

The 1996 interview we used of Judge Collins Seitz is housed at the Brown v. Topeka Board of Education Oral History Collection, AV collection no. 13, State Archives & Library, Kansas Historical Society.

(photo courtesy of the University of Delaware)

The all-White University of Delaware did not appeal Seitz’s ruling, but it admitted very few African American students in the subsequent years.

Even today the University of Delaware enrolls very few African American students.

In 1951, Sarah Bulah asked Louis Redding to help her secure a school bus to take her daughter to the Black school. He refused, saying he would only sue to secure her daughter a place in the White school near their home. She agreed and he filed suit. Similarly, a group of families in Claymont, asked Redding to help their children attend the local high school instead of having to travel to Wilmington to one of the few high schools in the state where African Americans could attend.

Once again Collins Seitz ruled in favor of the NAACP position and ordered the schools in Claymont and Hockessin to be integrated “forthwith.” He did not rule that segregation was unconstitutional. He said that such a ruling must come from the U.S. Supreme Court.

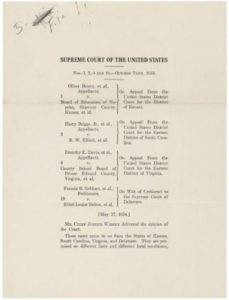

(photo courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Delaware Attorney General Arthur Young appealed Seitz’s ruling to the U.S. Supreme Court. He said that since Plessy v. Ferguson was the “law of the land,” Seitz should have given the state more time to bring the Black schools up to the level of the White schools.

The U.S. Supreme Court combined the two Delaware cases with other cases regarding school segregation and collectively named them after Linda Brown, a little girl in Topeka, Kansas whose parents wanted her to go to her neighborhood school.

The National Park Service, which has a museum dedicated to the case in Topeka, has information and resources at this website, Brown v. Board of Education.

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court ruled that segregation violated the 14th Amendment in Brown v. Board of Education.

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court ruled that segregation violated the 14th Amendment in Brown v. Board of Education.

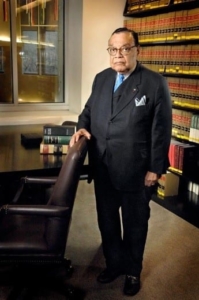

(photo courtesy of the U.S. Department of Transportation)

“He said you have to realize that there were five decisions which had held that segregation was constitutional. And giants at the law like Holmes, Brandeis, and Stone had voted that way. Next you have to realize that chancellor Seitz was the first person as a jurist – not as an advocate – to put in writing why in 1952 segregated schools were completely inconsistent with the American dream….

“These assets all combined in that young person Seitz, Frankfurter concluded, and demonstrated that history, including legal precedents of the Supreme Court, could be made to bow before the sheer stubbornness of a human conscience.”

-William Coleman

William T. Coleman, Jr., was secretary of transportation under President Richard M. Nixon. Earlier in his career he clerked for Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter. In a memorial tribute to Collins Seitz in 1999 that was filmed by C-Span, Coleman told the story that Frankfurter credited Seitz’s influence for his vote in Brown v. Board of Education. (at 27 minutes)

(photo courtesy of the Library of Congress)

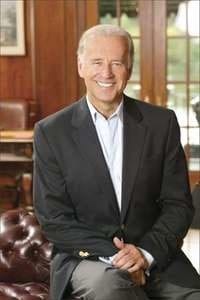

“If everybody thinks it was tough – or easy I should say – making the decision he made in the ’50s I want you to remember a little bit of turmoil that occurred here when we had a thing called busing which pales, pales, by comparison in terms of the decision he made….

“We all herald them now. We all stand there and say they were obviously the right thing to do. But hardly anybody from Claymont, Delaware where I’m from or St. Lenas, the school I went to, thought your dad did the right thing then. Some of the very people in this courtroom did not have the courage to stand up when he made the decision and say that is the correct decision, I know that to be true, count me in with him.”

At the same memorial tribute to Collins Seitz, then-Senator Joe Biden spoke of the courage that Seitz displayed. (at 44 minutes)

That summer, Louis L. Redding and a local minister talked with a group of families in Milford, Delaware. Eleven African American students had graduated from ninth grade and were planning on attending Jason High School in Georgetown.

“We were told that this was going to be a monumental opportunity for us and make sure we were on our best behavior, respect the teachers. We were 11 kids from Milford, Delaware. We didn’t stroll into the school, we weren’t trying to come in with an attitude.

We were just happy to get an education from an all-White school because we knew one thing for sure that getting an education from an all-White school was going to give us an opportunity.”

– Orlando J. Camp

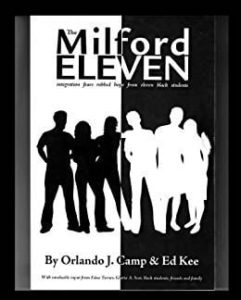

Orlando J. Camp reflected on his experience and that of his classmates in a 2011 book, The Milford 11: Integration Fears Robbed Hope from Eleven Black Students.

Orlando J. Camp reflected on his experience and that of his classmates in a 2011 book, The Milford 11: Integration Fears Robbed Hope from Eleven Black Students.

Camp’s book drew on a 1998 article in Delaware History by Walter “Ed” Kee.

“A leading businessman, not terribly well respected in the community, but he…had the tractor dealership and all the farm equipment dealership. So he was of the mind to be against integration and a lot of his clientele the rural farm people or other people didn’t like it and he had something to do with at least financing Bryant Bowles to come over here.”

– Walter “Ed” Kee, Interview with Karin Chenoweth for ExtraOrdinary Districts podcast

Walter “Ed” Kee, who later became Delaware’s Secretary of Agriculture, had moved to the Milford school district in the 1990s and heard rumors of trouble that had occurred there years before. He subsequently unearthed a number of documents and stories for a master’s thesis and the 1998 article and is widely credited with preserving the history of the Milford 11.

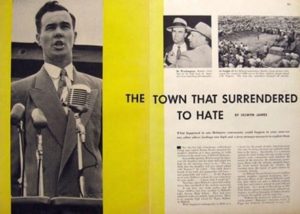

“The people out there have asked me to announce that they are in favor that if any Negro walks into any school anywhere in Delaware Monday to have a statewide walkout in the schools to support ‘em.”

– Bryant Bowles

Redbook Magazine was one among many publications that wrote about Bowles’s campaign to stop the desegregation of Milford High School and the rest of Delaware.

The Delaware State Archives houses a collection of historic audio recordings made by radio station WKSB of rallies and meetings at which Bryant Bowles spoke.

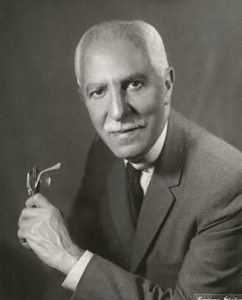

(photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution)

“Bryant came down again with boycotts and going to burn the building down and that sort of thing. I was asked my opinion and I said that the Supreme Court has spoken and that’s the law of the land and that these children did not disrupt either the curriculum of the school, they didn’t contaminate anybody, the walls did not fall apart and they had a right to be there. From then on I was accused that the reason I ruled that way was because I was a Jew.”

– Delaware Attorney General Arthur Young

The University of Delaware Library Special Collections holds an interview with Arthur Young conducted in 1971 in which he discusses Bryant Bowles and the Milford 11.

The Delaware state school board criticized the Milford School Board for not getting prior approval for enrolling African American students into the White school. This, even though Attorney General Young had said the Milford School Board could not legally have refused admission to the Milford students.

The Delaware state school board criticized the Milford School Board for not getting prior approval for enrolling African American students into the White school. This, even though Attorney General Young had said the Milford School Board could not legally have refused admission to the Milford students.

The Delaware State Archives displays the state school board’s “Suggested Policies for Opening of School” issued on August 19, 1954

(photo courtesy of the Library of Congress)

The Milford School Board members resigned, leaving the running of the schools to the state. The state board dis-enrolled the 11 Milford students who were African American and re-enrolled them in Jason high School, 16 miles away. That was the end of desegregation not only in Milford but in lower Delaware for more than a decade. It was not until 1967, when the Department of Health, Education and Welfare under President Lyndon Johnson threatened to withhold funds unless schools desegregated, that Delaware dismantled its segregated schools.

After his death in 1999, the University of Delaware named a building and a professorship after Louis L. Redding. Several schools are named after him as well.

Although Delaware was considered one of the most integrated states in the country at the end of the 20th century, UCLA’s Civil Rights Project reported in 2014 that it slipped back quickly after courts freed Wilmington from its cross-jurisdictional busing program.

(photo courtesy of Emory University)

“For all of the kind of virulent backlash to the work to the civil rights work that Louis Redding did, he was actually just making a very modest kind of request of state officials, of White citizens, which was to recognize the basic constitutional rights of African Americans. No more, no less. He was not asking for a kind of radical transformation of the system. He wasn’t asking that Blacks enjoy some great new privileges and advantages in society.

“All he was saying is, look there is this thing called the Constitution, there is this thing called the 14th Amendment. And then there is this long public policy record of inequality and inequity that has systematically diminished the standing —political, economic, and social standing — of African Americans citizens. That’s wrong and there is a simple remedy for it: desegregate the schools.”

– Brett V. Gadsden

Brett V. Gadsden is associate professor of history at Northwestern University.

He is author of Between North and South: Delaware, Desegregation, and the Myth of American Sectionalism, University of Pennsylvania Press.

This episode of ExtraOrdinary Districts was made possible with the support of Overdeck Family Foundation.