Of the 26 states analyzed, 13 states enrolled fewer than one-quarter of their Latino children in state-funded preschool programs, and 10 states enrolled fewer than one-quarter of their Black children

WASHINGTON (November 6, 2019) — High-quality early childhood education (ECE) is important to the rapid development that happens in the first five years of a child’s life and has long-lasting benefits well into adulthood. But many children, largely Black and Latino, are not given access to nor are being served by high-quality, state-funded ECE programs, according to a first-of-its-kind analysis by The Education Trust. The report examines the accessibility and quality of state-funded preschool programs for 3- and 4-year-old Black and Latino children during the 2017-2018 school year and finds that, out of the states analyzed, no state provides both high-quality and high-access ECE for these children.

For this research, Young Learners, Missed Opportunities: Ensuring That Black and Latino Children Have Access to High-Quality State-Funded Preschool, Ed Trust sought to answer two questions: Do Black and Latino students get access to these programs? And are these programs high-quality? To measure quality, Ed Trust used the widely respected National Institute for Early Education Research’s (NIEER) minimum quality standards benchmark rating, which consists of 10 benchmarks that represent research-based process quality standards for effective ECE.

Ed Trust leveraged NIEER’s definition of a state-funded preschool program: A state-funded preschool program is subsidized, controlled, and directed by the state, and primarily focuses on early childhood education. The program must also serve young children that are preschool age (usually 3 and/or 4 years old). To be included in this study, a preschool program must include at least 1% percent of a state’s 3- or 4-year-old population. The program must offer a group learning experience to children at least two days per week and must also be distinct from the state’s system for subsidized child care. A program may serve children with disabilities but does not serve children with disabilities as its primary focus. Moreover, we considered state supplements to the federal Head Start program as state preschool programs if they substantially expand the number of children served, and if the state assumes some administrative responsibility for the program.

When exploring both access and quality, Ed Trust found:

- Only 1% of Latino children and 4% of Black children in the 26 states analyzed were enrolled in high-quality state-funded preschool programs.

- In 11 of 26 states, Latino children are underrepresented in state-funded preschool programs. In three of those states, so are Black children.

- Access is lower for Black and Latino 3-year-olds than for Black and Latino 4-year-olds.

- Far too few state-funded preschool programs collect and report race and ethnicity data.

“Our data is devastating. No state provides the two essential elements for a strong early start for our nation’s Black and Latino children — quality and access,” said lead researcher, Carrie Gillispie, Ed.D. “Despite overwhelming research on the value of high-quality preschool, states continue to willfully neglect our youngest students of color.”

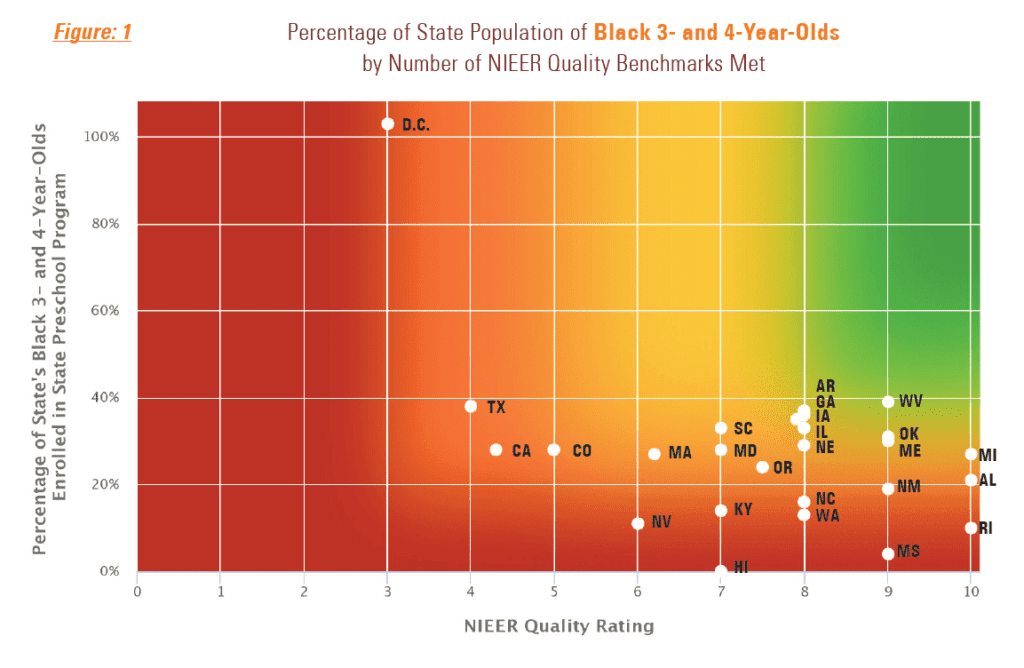

Of the 26 states analyzed, 13 states enrolled fewer than one-quarter of their Latino children in state-funded preschool programs, and 10 states enrolled fewer than one-quarter of their Black children. The report found that, although well-intentioned, some states with “universal” programs lack sufficient program quality. For example, DC’s program reaches nearly all of its Black 3- and 4-year-olds and 61% of its Latino 3- and 4-year-olds, making it particularly strong on access. But it was rated only 3 out of 10 for quality. On the other hand, states with high quality often serve very few Black and Latino children. For instance, Mississippi’s program was rated a 9 out of 10 for quality, but served only 1% of its Latino children and 4% of its Black children.

Georgia, Oklahoma, and West Virginia, however, proved to be bright spots with relatively high access and high quality for Black and Latino 4-year-olds. Georgia serves more than 60% of the state’s substantial number of Black and Latino 4-year-olds, and its program meets 8 of 10 of NIEER’s quality benchmarks. Oklahoma provides access to just over 60% of its Black and Latino 4-year-olds, while West Virginia provides access to 47% of its Latino 4-year-olds and 75% of its Black 4-year-olds. Both programs met 9 out of 10 of NIEER’s quality benchmarks. A full analysis showing how individual state programs fare for Black and Latino children is available via an online tool.