Degree Attainment of Latinos Lags Far Behind That of Whites

In last year’s briefs, we analyzed national and state data on degree attainment for Black and Latino adults , ages 25-64. Slightly more than 22 percent of Latino adults have earned an associate degree or higher, compared with roughly 47 percent of White adults. For perspective, the current degree attainment levels of Latinos are about 10 percentage points below those of White adults in 1990 — over a quarter of a century ago. To make matters worse, inequities in degree attainment are reinforced by gaps between Latino and White young adults, ages 25-34. Despite some gains, Latinos still trail their White peers considerably in the share of young adults who have a college degree.

Young Latino adults are an important group because they represent about one-third of all Latino adults and about 20 percent of all young adults in the U.S. The degree attainment of young Latino adults is critical not only because it reflects the state of equity (or lack thereof) for Latinos who are likely to have progressed through schools and colleges in the U.S., but because young Latino adults will remain in the workforce and raise families for decades to come. But this does not necessarily mean young Latino adults are being given a fair opportunity to attain a college degree.

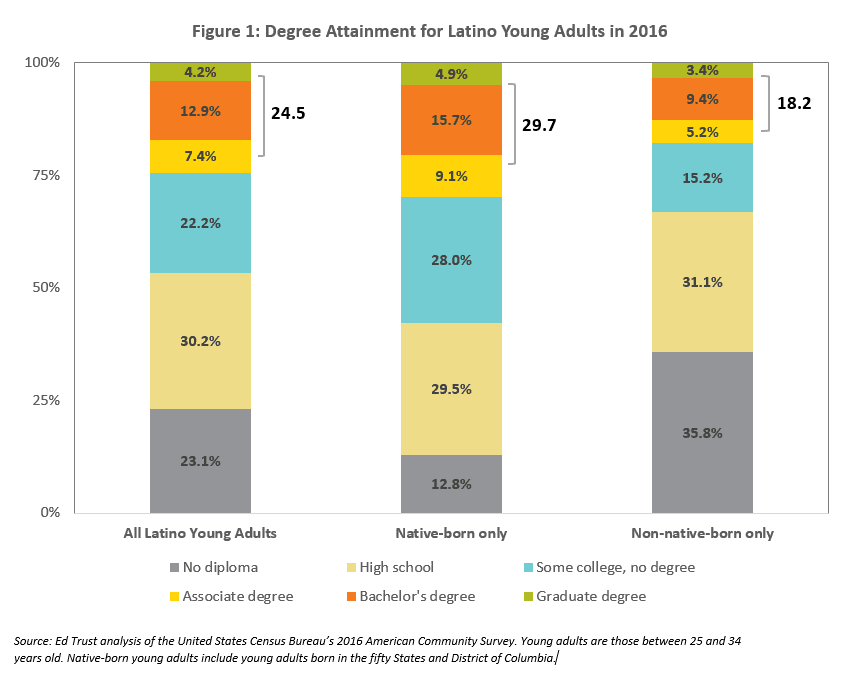

Degree attainment for young Latino adults is 24.5 percent (Figure 1)—that is, not much better than the roughly 1 out of 5 older Latino adults who have a college degree. Young Latino adults are about half as likely as their White peers to hold at least an associate degree. The gap is even more pronounced at the bachelor’s level and above, with roughly 17 percent of young Latino adults having a bachelor’s or graduate degree, compared to 40 percent of young White adults.

On a more positive note, the share of young Latino adults with a degree has increased 9.5 percentage points since 2000. Much of this improvement is due to the emergence of second-generation (and above) Latinos who were born in the U.S. Generally, those born in the U.S. have more formal education than non-native-born Latinos. For instance, nearly 90 percent of native-born Latino adults, ages 25-34, hold at least a high school diploma, while only two-thirds of their non-native-born peers have a diploma or its equivalent. (In our Latino degree attainment brief , we discuss this in depth.) With that in mind, how much has degree attainment improved for young Latino adults, if we look specifically at those who were born in the U.S. and who experience fewer immigration-related barriers? Have the gaps narrowed?

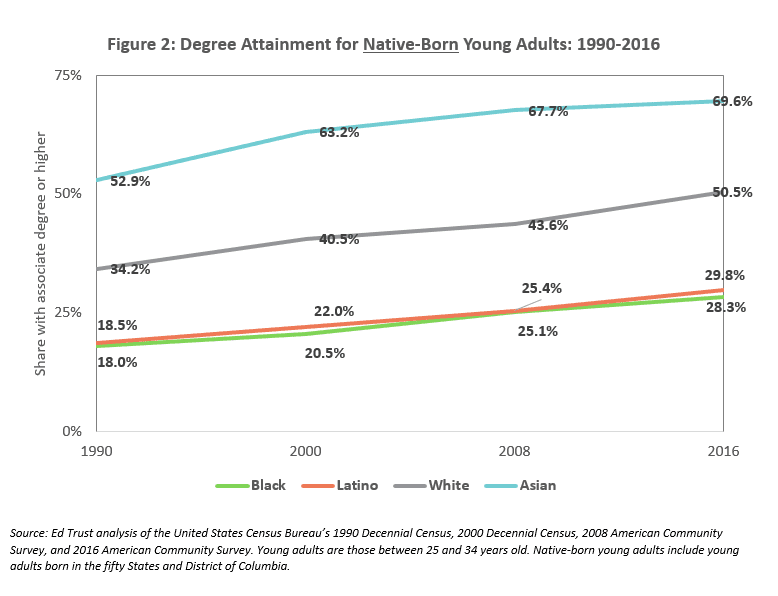

Unfortunately, gains in degree attainment for native-born Latino adults, ages 25-34, have been slow to materialize next to those for White Americans (Figure 2). Among young adults born in the U.S., the trajectory of Latino degree attainment mirrors the progress of Black Americans since 1990, while degree attainment has grown much faster for White Americans. In fact, degree attainment for native-born young Latino adults increased from 18.5 percent in 1990 to slightly less than 30 percent in 2016—remaining well below the level of degree attainment for their White peers in 1990. The attainment gap between Latino and White young adults has steadily widened over the past quarter-century, which suggests that more progress on higher education access and degree completion for Latinos is needed to start closing gaps.

That’s troubling—and not merely because it suggests that many Latinos in schools and colleges in the U.S. are experiencing vast educational inequities. Latinos are the fastest growing segment of the U.S. population: From 2000 to 2016, the share of Latino young adults born in the U.S. rose to 55 percent, up from about 38 percent, and it’s still growing. Latinos will soon make up a large share of the U.S. workforce and have a hand in shaping the nation’s economy for years to come. By 2050, Latinos will be almost one-third of the U.S. workforce (not to mention the country’s tax base), according to the Pew Research Center. What’s more, we know that good jobs increasingly go to the more educated: the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts that most jobs in the coming years will require at least some college education, so unless we want American businesses to be stunted by labor shortages (and our economy to be stunted along with them), our leaders might want to make Latino college access and completion a greater economic imperative. It’s more than a matter of fairness. It’s smart policy.