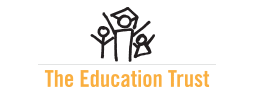

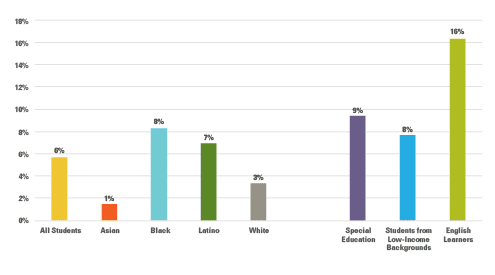

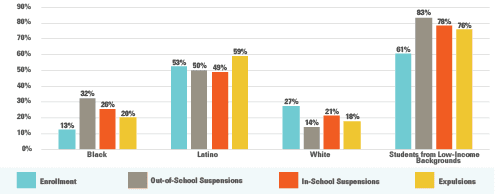

Ensuring Safe and Supportive School Climates in Texas

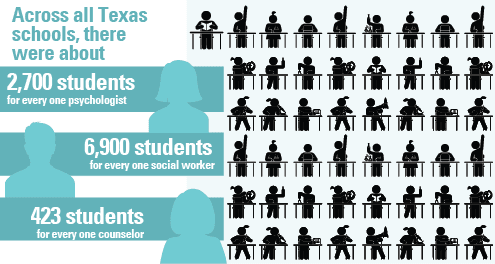

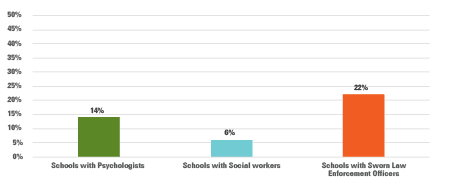

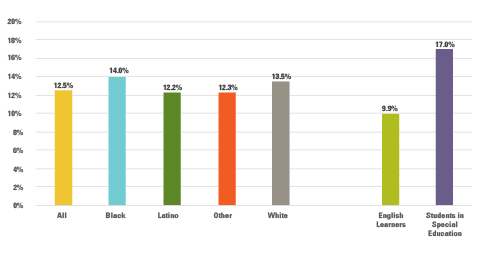

Texas is facing a pivotal moment. The coronavirus has negatively affected Texans’ health, economic, and educational well-being. The pandemic has exacerbated inequities that have long been issues for Texans of color and Texans from low-income backgrounds. Across the country, Black, Latino, and immigrant communities are suffering from disproportionate job losses, virus infection, and death rates. In the middle of this global health crisis, the nation is experiencing another crisis — a national reckoning on race that has been spurred by extensive protests against police brutality. Adults and young people alike are demanding more from their state and local leaders. This moment will require leaders to address the educational inequities that have existed for some time, the consequences of COVID-19 that are set to make matters worse, along with the racial injustices that students of color are facing in and outside of schools. Disparities in opportunities to learn have left thousands of Texas students — particularly Black, Latino, and students from low-income backgrounds — disconnected from school.[1] Once school buildings closed their doors, students and their families were separated from the educators and school communities that provide the critical supports that they need. According to a poll at the beginning of school closures, only 23% of Texas parents reported that their child’s school was connecting them to resources to help with food, housing, employment, health, and other emergency needs.[2] A statewide survey of school districts also indicated that 17% of students lack access to high-speed internet and 30% lack adequate tablets or laptops for remote learning.[3] These barriers, if unaddressed, will have lasting impacts on the future of young Texans. During a typical school year, schools are not only places where students engage with curriculum; they are the center of communities. Schools provide meals, counseling, and some connect students to mental and physical health supports. To keep students and families healthy during this pandemic, many schools will not operate as usual. Nevertheless, it is critical that schools continue to play a central role, provide needed resources, and foster the positive school climates necessary to promote the mental health and academic achievement of Texas students. WHAT IS SCHOOL CLIMATE? School climate describes the experience of school life for adults and students, including the norms, values, interpersonal relationships, and practices that influence both mental health and conditions for learning.[4] A positive school climate means people feel safe, cared for, connected, and engaged in learning and teaching together.[5] Students who attend schools with a positive school climate have increased self-esteem and self-concept, decreased absenteeism, reduced behavioral issues, and disciplinary actions,[6] and increased school completion.[7] School climate matters for academic learning and student engagement. Even though school climate is critical to all students’ academic success, students of different races and ethnicities experience school climate differently.[8] Black and Latino students report having less favorable experiences of safety, connectedness, relationships with adults, and opportunities for participation.[9] Without targeted action, Black and Latino students are even more likely to be marginalized and feel disconnected from their schools, especially as COVID-19 continues to disrupt education.[10] POOR SCHOOL CLIMATES CAN RESULT IN PUSH OUT. One of the more harmful consequences of poor school climate is that students may disengage from school all together. Negative school climates alienate students and can result in push out.[11] Schools that are not proactive in addressing chronic absenteeism, have high exclusionary discipline rates, and lack supportive school staff can decrease the likelihood that students will complete high school.[12] The economic and social consequences of this are well documented in research: taxpayers spend millions on youth and adult justice system costs, as well as health and social services, when students do not complete high school,13 and adults without a high school degree are more likely to be unemployed and have lower salaries.14 This is particularly troubling for English learners, who are pushed out at much higher rates than their peers in Texas (Figure 1). Texas has a lot of work to do. The existing data paints a bleak picture of the experiences of historically underserved students and the supports they receive in Texas schools. There is no single measure of school climate, but a combination of measures, such as data on exclusionary discipline, staffing, nd chronic absenteeism can paint a picture of the ways in which students, families, and educators experience school. EXCLUSIONARY DISCIPLINE Exclusionary discipline practices, like suspension or expulsion, prevent students from fully participating in their education by removing them from their classrooms or learning environments. Schools that use less punitive, more positive alternatives to addressing school-based conflicts create school climates that are more nurturing and welcoming.[15] Contrary to the belief that exclusionary discipline policies make schools safer, evidence shows that exclusionary discipline is not an effective method for changing students’ behavior in schools and results in harmful long-term social-emotional and academic outcomes.[16] Across the country, Black students are more likely to be subjected to exclusionary discipline than their White peers,[17] even though they are not more likely to misbehave.[18] Texas is no exception. In Texas, Black students are five times more likely and Latino students are almost twice as likely to be suspended out-of-school than their White peers.[19] While Black students make up only 13% of Texas’ student body, 32% of out-of-school suspensions and 20% of expulsions were given to Black students (Figure 2). Students from low-income backgrounds are also more likely to be disciplined. While they make up 61% of enrollment, 83% of out-of-school suspensions and 76% of expulsions were given to students from low-income backgrounds (Figure 2). The overwhelming majority of exclusionary punishments in Texas that result in missed school time are categorized as code of conduct violations (Figure 3). Most students are being penalized for violating codes of conduct that lend themselves to discretionary enforcement and rarely threaten the physical safety of other students. Non-violent offenses in codes of conduct are quite broad and can include anything from “classroom disruption” to “offensive language.” This is especially true in Texas, where many schools are given discretion over dress codes and other disciplinary standards. For example, Dallas Independent School District’s code of conduct categorizes “dress and grooming code violations” as a Level I offense, which may result in an in-school suspension.[20] This means a student could miss class time for not having a clean uniform or the proper shoes. In Houston, cutting class or skipping school is a Level II violation of the code of conduct, which can result in either an in-school suspension.[21] In this case, an exclusionary response is counterproductive — students who choose to miss school should not be forced to miss more school. On top of that, discretionary codes of conduct violations are susceptible to bias.[22] Exclusionary punishment for discretionary offenses disproportionately harms Black students even though Black students are not more likely to act out in school.[23] Exclusionary disciplinary methods not only isolate students, they cause psychological, and sometimes physical harm. Texas is one of 22 states that continues to allow corporal punishment in K-12 schools.[24] Texas also has one of the highest state corporal punishment rates in the country, with 4.6% of students enrolled in schools practicing corporal punishment — amounting to 418,332 students in the 2013-2014 school year.[25] Under Texas law, corporal punishment means the deliberate infliction of physical pain by hitting, paddling, spanking, or any other use of physical force as means of discipline.[26] Texas Education Agency (TEA) provides no guidance or regulations on the uses of corporal punishment, which leaves this practice open to egregious disparities in its use.[27] The disproportionate use of corporal punishment on students with disabilities nationally and in Texas is a concerning trend. In the 2015-2016 school year, students with disabilities accounted for only 14% of Texas enrollment, but they represented 21% of students receiving corporal punishment in the state.[28] These practices undermine the creation of safe and welcoming schools needed to support the success of students in Texas. TEXAS’ HB674 REDUCED THE NUMBER OF OUT-OF-SCHOOL SUSPENSIONS IN EARLY GRADES, BUT TENS OF THOUSANDS OF STUDENTS WERE STILL SUSPENDED AND DISPARITIES STILL EXIST.[29] In 2017, the Texas legislature passed HB674, a law that prohibits the use of discretionary out-of-school suspensions for pre-K through second grade students.[30] A Texans Care for Children report found that in the first year of the bill’s implementation, out-of-school suspensions in pre-K – 2nd grade dropped significantly from 36,475 to 7,640. While an improvement, 70,000 total suspensions (which includes out-of-school and in-school suspensions) were still given out to students in early grades in 2017-2018.[31] Texas districts also disproportionately suspended Black students, students in foster care, and students with disabilities.[32] This represents a significant amount of lost learning time, potentially harmful social-emotional effects, and further marginalizes Texas’ youngest learners. RECOMMENDATION: REDUCE & REPLACE EXCLUSIONARY DISCIPLINE Exclusionary discipline methods have harmful and long-lasting effects on students. Recommendations to reduce the use of these methods in Texas include: SCHOOL SUPPORT STAFF School support staff play a large role in establishing a positive school climate. These professional adults include social workers, school psychologists,[33] and school counselors, who provide specialized instructional support or mental health services to students. By building relationships, school staff can connect students to resources, establish positive behavior management systems that do not rely on exclusionary practices, and support the academic success of students.[34] Black students, Latino students, and students from low-income backgrounds, for example, are more likely than their White and affluent peers to identify their school counselor as the person who had the most influence on their thinking about postsecondary education.[35] Texas, however, is well above recommended levels of student-to-support-staff ratios to maintain safe and supportive learning environments. The National Association of School Psychologists recommends a ratio of 500 to 700 students to every one school psychologist, and a ratio of 400 students to one social worker.[36] Across all Texas schools, there were about 2,700 students for every one psychologist and about 6,900 students for every one social worker in the 2018-19 school year.[37] These high student-to-staff ratios translate to little or no access to guidance and mental health resources at the school level. More than three-quarters of Texas schools did not have any school psychologists or social workers on campus, according to 2015-16 CRDC data (Figure 4). Compared to other states, Texas ranked among the bottom 10 states for percentage of public high schools with social workers (ranked 45 out of 50 states and DC) and school psychologists (ranked 44 out of 50 states and DC).[38] School counselors, another critical member of the school support team, are also limited in Texas. In the 2018-19 school year, there was one counselor for every 423 students in Texas.[39] The American School Counselor Association recommends a ratio of 1:250.[40] Across all schools, only 5% of students were enrolled in a school where there is a recommended amount of school counselors. And about 4% of students — just over 230,000 children — do not have access to a school counselor at all.[41] In addition to counselor shortages, many districts and schools assign counselors to work beyond their counselor duties. Lack of role clarity leaves many school counselors with limited capacity to support the mental health and social-emotional needs of their students.[42] To put it plainly, Texas lacks adequate skilled and professional staff to ensure students have access to essential social-emotional and academic supports. TEXAS SCHOOLS ARE HEAVILY INVESTING IN POLICING, WHILE COUNSELING AND MENTAL HEALTH RESOURCES REMAIN LIMITED AND INEQUITABLY DISTRIBUTED. The data suggests that many Texas schools are investing more in resources that criminalize students, rather than support them. Police can create overly punitive school climates that adversely affect learning and disadvantage Black students, Latino students, and students from low-income backgrounds.[43] Yet, there are more schools with at least one sworn law enforcement officer than there are schools with at least one psychologist or social worker in Texas (Figure 4). FIGURE 4: PERCENTAGE OF TEXAS PUBLIC SCHOOLS WITH SUPPORT STAFF, 2015-2016 Source: U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, Civil Rights Data Collection, 2015-16, available at https://ocrdata.ed.gov/ StateNationalEstimations/Estimations_2015_16 In a recent report on school safety and climate in Texas schools, Texas Appleseed found that Texas school districts are unevenly resourced: The majority of school districts (59%) that reported having zero professionals were rural.[44] Students of color also endure more punitive school environments than their White peers in Texas. Districts and schools that serve more students of color in Texas have more law enforcement officers present than districts and schools with a majority of White students.[45] RECOMMENDATION: INVEST IN SCHOOL SUPPORT STAFF Counselors, social workers, and school psychologists are invaluable members of school communities, but Texas schools do not have enough of them. To increase students’ access to school support staff, Texas should: CHRONIC ABSENTEEISM School attendance is a prerequisite for academic success and is linked to third grade reading proficiency[46] and graduation.[47] But, when students do not feel connected, safe, and supported at school, they may be less likely to show up every day.[48] Chronic absenteeism can, therefore, be an indicator of poor school climate. It can also be a measure to identify students who have not been supported enough to be on-track academically and could benefit from additional supports. Reducing chronic absenteeism is one way Texas can improve and address inequities in student outcomes. In the 2018-2019 school year, 12.5% of all Texas students missed 10% or more of school days according to a forthcoming report by Children at Risk. Black students had the highest rate (14%) of chronic absenteeism compared to students in other racial and ethnic groups; however, the biggest disparities were for students served by special education programs. Nearly 1 in 5 students in special education were chronically absent that year (Figure 5). Of course, students may be chronically absent for reasons beyond their control, such as unstable housing, unreliable transportation, and a lack of access to health care. Students who live in communities with high levels of poverty are particularly vulnerable to these difficulties.[49] Students with disabilities may also have unique health, accessibility and resource challenges that contribute to frequent absences from school.[50] And the economic and health effects of COVID-19 will likely exacerbate these barriers for many students. There can also be barriers within schools and districts that discourage student attendance. For example, unsafe and dirty learning environments can make students feel anxious and fearful; and schools that lack a culture of belonging and connectedness can discourage students from participating in class or engaging academically.[51] Ensuring the conditions for a positive school climate can make a world of a difference for all students, but particularly the most vulnerable. Some absences for students with disabilities may be due to disabilit y-specific health issues, but many absences likely relate to insufficient environmental supports for students with disabilities, which exclude these students both physically and socially.[52] Schools and districts can encourage attendance by proactively engaging students and families and making schools places students want to go. LEARNING FROM LOCAL SUCCESS: SCHOOLS AND DISTRICTS CAN AND SHOULD ADDRESS CHRONIC ABSENTEEISM Schools, districts, families, and community service providers can target chronic absenteeism with focused efforts that consider which students are absent and why. According to a recent study from E3 Alliance, acute illness was a prominent cause of student absences in Central Texas, especially for students from low-income backgrounds. Based on this finding, E3 Alliance, school districts, and partners initiated targeted interventions, such as no-cost, on-site flu immunization programs at 136 schools. Since 2014, focused regional efforts have lowered overall student absences and kept tens of thousands of Texas students in school, able to learn.[53] RECOMMENDATION: DEFINE, REPORT, AND REDUCE CHRONIC ABSENTEEISM Chronic absenteeism is a solvable problem. Recommendations for state action include: Texas is failing at ensuring students — especially Black and Latino students, students from low-income backgrounds, English learners, and students with disabilities — are engaged and have equitable access to the social-emotional and academic supports needed to thrive. These inequities are not new, and there is more urgency to address them than ever before. AT THIS PIVOTAL TIME, TEXAS MUST STRENGTHEN ITS EFFORTS TO IMPROVE SCHOOL CLIMATE. In the last legislative session, the Texas legislature instated laws related to school climate and the mental health of Texas students: SB11, HB18 and HB19. SB11 is an extensive bill passed to increase school safety and security in the wake of tragic school shootings that encourages districts to improve school safety infrastructure and trauma-informed practices.[55] It requires that TEA, in coordination with the Texas School Safety Center, establish a Safe and Supportive School Program (SSSP), which has several functions including promoting positive school climates through the use of school climate surveys and multi-tiered systems of supports (MTSS) that systematically align initiatives, resources, staff development, and services. HB18 and HB19 complement this bill by bolstering school staff professional development, counseling programs, and mental health services for students.[56] School safety extends beyond policing and security measures — as evident in these comprehensive bills, it includes holistic mental health supports and resources that create positive school climates. While the Texas legislature and TEA are deploying resources and guidance to support schools’ and districts’ mental health and school climate efforts, schools and districts may face resource barriers to proper implementation. The School Safety Allotment included in SB11 provides limited dollars ($9.72 for each student in average daily attendance) for schools to implement the legislation’s provisions and includes facilities hardening and the presence of School Resource Officers (SROs) as allowable uses.[57] Districts and schools will need continued assistance in the coming years to prioritize and allocate resources wisely to fully implement the mental health legislation. Given the impact of the pandemic on students’ physical and social-emotional well-being, disproportionately felt in low-income communities and communities of color, funding for the School Safety Allotment must be maintained and focused on evidence-based strategies that create safe and supportive school climates. RECOMMENDATION: IMPLEMENT THE SAFE AND SUPPORTIVE SCHOOLS PROGRAM WITH FIDELITY AND EQUITY Recommendations to strengthen Texas’ mental health and school climate efforts include: TEXAS POLICYMAKERS MUST ADOPT POLICIES THAT FOSTER SAFE, SUPPORTIVE, AND POSITIVE SCHOOL ENVIRONMENTS. The data shows there is an urgent need to ensure Black students, Latino students, English learners, students with disabilities, and students from low-income families have learning environments, whether in-person or remotely, with positive climates that are conducive to learning. Texas’ efforts should also be leveraged and adapted to target the challenges students face today amid the pandemic. Below are actions the state should take: NOW IS THE TIME TO PRIORITIZE THE MENTAL HEALTH AND ACADEMIC WELL-BEING OF ALL STUDENTS. Texas has a critical responsibility to ensure that all students attend schools that are physically and emotionally safe, encourage strong interpersonal relationships, and support all students’ well-being and academic achievement. This must be a top priority in the state to recover from the consequences of COVID-19 that have exacerbated years of inequities for students from low-income backgrounds, Black and Latino students, students with disabilities, and English learners.

FIGURE 1: TEXAS FOUR-YEAR PUSH-OUT RATE, GRADES 9-12, BY STUDENT GROUP (CLASS OF 2018)

Source: Texas Education Agency, 2018-2019 Pocket Edition, Completion Grades 9-12 Class of 2018.

FIGURE 2: DISCIPLINARY ACTIONS BY RACE/ETHNICITY AND INCOME, 2018-19

Source: Texas Education Agency, Office of Governance and Accountability Division of Research and Analysis, Enrollment in Texas Public Schools 2018- 19, and Texas Education Agency, Student Data, State level Annual Discipline Summary, Discipline Reports 2018-19.

FIGURE 3: REASON FOR DISCIPLINARY ACTION, 2019

Source: Texas Education Agency, Discipline Action Group Summary Reports, Counts of Students and Actions by Discipline Action Reasons and Discipline Action Groups, 2018-2019

FIGURE 5: PERCENT OF TEXAS STUDENTS WHO MISSED 10% OR MORE SCHOOL DAYS, 2018-19

Source: CHILDREN AT RISK. (forthcoming). Chronic Absenteeism Analysis 2016-2019.

ENDNOTES

Teachers?br=PK-12 ; and Texas Education Agency. PEIMS Standard Reports Overview. 2018-2019 Student Enrollment, Statewide Totals. Retrieved from: https://rptsvr1.tea.texas.gov/cgi/sas/broker?_service=marykay&program=adhoc.addispatch.sas&major=st&minor=e&charsln=120&linespg=60&_debug=0&endyear=19&selsumm=ss&key=TYPE+HERE&grouping=e+&format=W

on attendance in the time of COVID, to please see: https://tea.texas.gov/sites/default/files/covid/sy_2020-21_attendance_and_enrollment_faq_remote_only.pdf