Aging out of foster care

Each year, 20,000 young people begin transitioning to independent adulthood, typically at or around the age of 18. However, those who are aging out of foster care are less prepared for self-sufficiency. They’re less likely to have secure support networks, stable housing and employment, medical insurance, and they’re less likely to have a safety net to fall back on during any crisis — not just a pandemic.

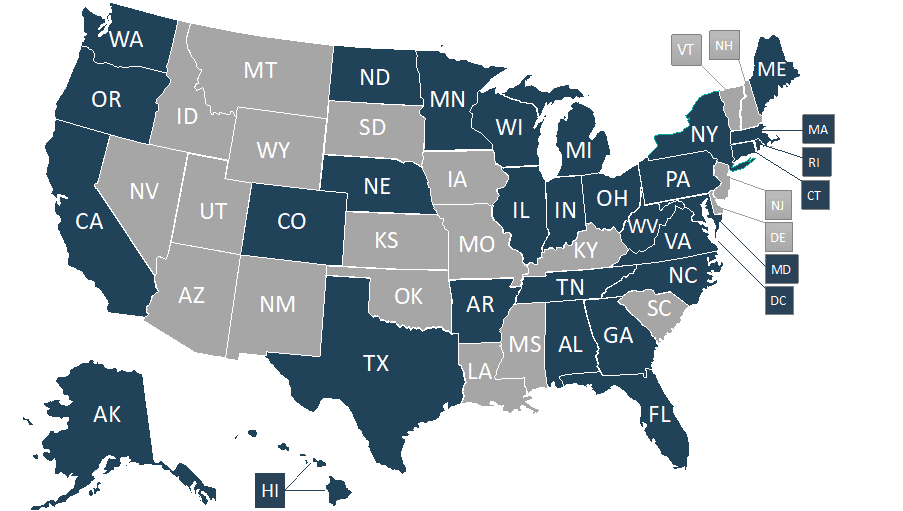

The good news is that some policymakers recognize that many 18-year-olds are not prepared for self-sufficiency, and states now have the option to provide extended foster care up to age 21. States can also provide meaningful support for older foster youth via transitional services including, but not limited to, independent-living skills training, college education, vocational training, and housing assistance through the Chafee Foster Care Independence Program. States receive federal reimbursement for services that help young people between the ages of 18-21, or up to 23 in some cases, transition to independence in states with extended foster care. Currently, 30 states (and the District of Columbia) provide extended foster care. The bad news is that despite urgent calls for child welfare reform, 20 states have neglected to do so. As a consequence, this vulnerable population is at a severe disadvantage when it comes to transitioning to adulthood.