TACKLING THE EFFECTS OF COVID-19 WILL REQUIRE TEXAS TO INVEST IN STUDENTS’ ACCESS TO STRONG AND DIVERSE TEACHERS. Research shows that teachers influence student learning more than any other in-school factor, especially for students who are behind.[1] When students have strong teachers, year after year, the effects add up. For example, students with a highly effective math teacher can get up to four additional months of learning compared with students with a lower-performing math teacher.[2]

Teachers are more important than ever before. They will be essential to supporting students who have fallen behind academically as a result of pandemic-related school closures, especially students with limited distance-learning resources and students experiencing instability or emotional distress.[3] However, not all students have access to the educators they need and deserve. Black students, Latino students, English learners, and students from low-income backgrounds have less access to strong and diverse teachers in Texas. And, without meaningful action, this will be even more true on the other side of this crisis.

Due to systemic under-resourcing and denial of opportunity for historically marginalized students and communities, disparities in student achievement across race, ethnicity, and language have long existed in Texas. And results from the 2019 State of Texas Assessment of Academic Readiness (STAAR) indicate that inequities have yet to be addressed. Texas managed to get 56% of White students to grade level or above in third grade reading, but only got 33% of Black students, 39% of Latino students, and 39% of English learners to grade-level or above.[4] Students from low-income backgrounds were also left behind. Texas got only 35% of students from low-income backgrounds to grade-level or above on the third grade STAAR.[5] These outcome disparities, which have lasting effects on children and Texas’ economic future, are a direct result of disparities in resources and learning opportunities, including access to strong and diverse educators who are foundational to student success.

THE FUTURE OF TEXAS DEPENDS ON THE SUCCESS OF THE STUDENTS WHO HAVE BEEN HISTORICALLY DISADVANTAGED.

TEXAS MUST TAKE AN HONEST LOOK AT THE DATA TO ADDRESS EDUCATOR INEQUITIES IN ITS CURRENT SYSTEM.

Texas is a racially and ethnically diverse state, and the population is projected to grow increasingly diverse.[6] People of color make up 61% of the current population and are expected to make up an even greater share (around 71%) of the state’s total population by 2050.[7] The future of Texas depends on the success of the students who have been historically disadvantaged. In 2019, 1 in 5 students was an English learner, 61% of the state’s students were from low-income backgrounds, and students of color made up the majority of Texas’ public school students.[8]

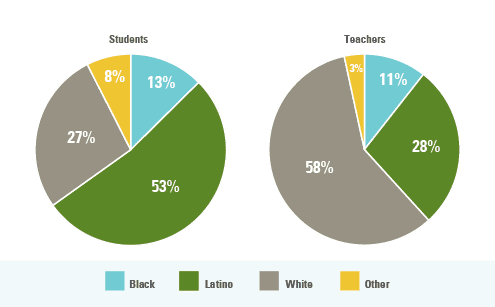

Even though 65% of the state’s students were Black or Latino, only 38% of teachers were either Black or Latino (Figure 1). A teacher workforce that reflects the student body has positive benefits for all students, and research has shown the benefits to be particularly high for students of color.[9] Students of color are more likely to attend school regularly, perform higher on end-of-year assessments, be referred to a gifted program, graduate high school, and consider college when they have had a teacher of the same race or ethnicity.[10] But in Texas, students of color are less likely than their White peers to encounter a teacher who looks like them. About 5 percent of Texas schools reported having no teachers of color on staff in 2019 — that equates to more than 100,000 Texas students attending schools without a single teacher of color.[11] While virtually every White student in Texas attends a school with at least one educator that matches their racial identity, about 4,600 Black and 21,000 Latino students lack this opportunity.[12]

RECOMMENDATION: SET GOALS & STRENGTHEN DATA TO TRACK PROGRESS

The only way for stakeholders to know how Texas is doing in its efforts to build a strong and diverse teacher workforce is to have access to useful, timely, and transparent data. Recommendations for making educator quality and diversity data more visible and actionable include:

- As part of the Tri-Agency Workforce Initiative, set clear and numeric goals at the state, regional, and district level to increase access to strong and diverse teachers. Publicly report, monitor, and track progress toward these goals.

- Sustain and strengthen the state’s data systems, including Accountability System for Educator Preparation (ASEP), by collecting and publicly reporting (a) teacher retention rates by race at the state and district level, (b) teacher vacancy data at the state and district level, and (c) candidate diversity at the EPP program-level within ASEP.

In addition to having little access to same-race teachers, students of color and students from low-income backgrounds are disproportionately taught by teachers with no previous classroom experience. Research shows that, for most teachers, effectiveness increases with experience, especially in a teacher’s first few years in the classroom.[13]

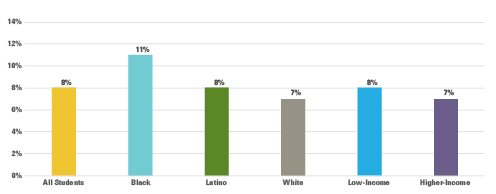

Of course, there will always be teachers at the beginning of their career. In Texas, 13% of teachers have less than one year of teaching experience.[14] But, Black fourth graders are nearly 60% more likely than their White peers to have a first-year reading teacher (Figure 2).

This is, in part, because of disparities across districts. Districts serving the largest populations of Black students, and students from low-income backgrounds in Texas have more teachers in their first year of teaching than districts serving smaller populations of these students. For example, districts with the most Black students have about two-thirds more beginner teachers (an average of 9%) as districts that serve the fewest Black students (an average of 5%).[15] The same is true for districts serving the most students from low-income backgrounds. An average of 8% of teachers are beginner in the highest poverty districts, compared with only 5% in districts serving the fewest students from low-income backgrounds.[16]

GIVEN THE DEMAND FOR EDUCATORS AND THE STATE’S DEMOGRAPHICS, DIVERSIFYING TEXAS’ TEACHER PIPELINES IS URGENT.

Diversifying the teacher pipeline starts with educator preparation programs (EPPs). There are multiple preparation routes in Texas that allow prospective educators to earn teaching certificates. Until recently, university-based programs enrolled the largest number of participants. In 2014, alternative certification programs became the most popular and racially diverse route to a teaching career in Texas.[17] More than three times as many Black participants, and more than twice as many male participants, are enrolled in alternative certification programs than in university-based programs.[18]

Despite alternative certification programs enrolling more Black candidates and male participants, the gender and racial characteristics of Texas’ teacher candidates, similar to the current teacher workforce, do not yet mirror the racial, ethnic, and gender composition of Texas’ public school student population.[19] And over the last five ears, the certification of new Black and Latino educators has not substantially increased.[20]

In addition, after two decades of increased enrollment in EPPs, the number of participants began to decline in 2009 and has not recovered to pre-recession levels, dropping to a 20-year low in 2018. Reduced EPP participation persists today, highlighting the importance of diversifying the educator pipeline to meet the state demand for new teachers.[21]

Both the Texas Education Agency and State Board for Educator Certification annually report important data to bring more transparency and accountability around Texas EPPs. The Accountability System for Educator Preparation (ASEP) dashboard provides useful information for school districts planning staffing and recruitment efforts. While ASEP shares data on accountability and performance indicators disaggregated by race and ethnicity, it lacks data on indicators and goals related to the retention of candidates of color and increasing the racial diversity of the workforce.[22]

RECOMMENDATION: CULTIVATE A DIVERSE EDUCATOR WORKFORCE

Grow Your Own programs have been shown to be an effective approach to increasing the racial diversity of the workforce.

- Texas should sustain and expand investment in GYO programs within the TEA’s next strategic plan and —

- Ensure the recruitment and selection of racially and linguistically diverse candidates is a clearly articulated priority and establish common performance measures for all programs to report regularly.

- Establish regional consortiums to facilitate partnership between school districts, EPPs, and other community-based programs to design, implement, and sustain GYO strategies to meet local teacher workforce needs.

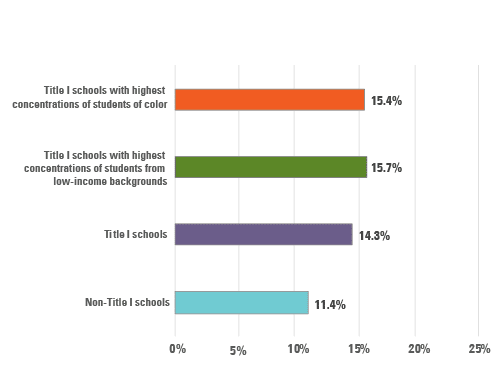

Disparities across schools exist as well. Title I schools have higher percentages of first-year teachers than non-Title I schools which serve fewer students from low-income backgrounds (Figure 3). And Texas’ Title I schools that serve the highest percentages of economically disadvantaged students and students of color have the highest percentage of inexperienced teachers (Figure 3).

IDENTIFYING HIGHLY EFFECTIVE TEACHERS THROUGH TEXAS’ TEACHER INCENTIVE ALLOTMENT (TIA)

There are many factors that contribute to effective teaching, and there is no one perfect measure. Proxies for educator quality, like having at least two or three years of classroom experience and infield certification, are helpful to understand where inequities exist. More recently, opportunities to better identify effective teaching and excellent educators have emerged through the use and propagation of multi-measure evaluation systems. Texas House Bill (HB 3) established the Teacher Incentive Allotment (TIA) to address three persistent challenges in Texas: recruiting teachers and addressing shortages, retaining teachers, and ensuring more equitable access to effective teachers. The TIA incentivizes districts to develop a multi-measure system that designates high-performing teachers as “recognized,” “exemplary,” or “master.” Districts can receive $3K to $32K per designated teacher, with higher incentives for teachers working in high-poverty and rural schools.[23]

TIA is a real opportunity for Texas to prioritize equitable access to strong teachers in high-need schools and districts. But, given the challenges posed by the pandemic, districts will need technical assistance and flexibility to apply for this opportunity and establish an equitable multi-measure system. So far, only 26 LEAs will benefit from funding under TIA for the 2019-2020 school year.[24] Maintaining this program and monitoring implementation to ensure evaluation systems are continuously improved for equity (e.g., incorporating cultural responsiveness, closing gaps in achievement, addressing potential bias, and teacher diversity into evaluation systems) could help all students in Texas access excellent instruction.

RECOMMENDATION: ENSURE EQUITABLE ACCESS TO STRONG EDUCATORS

Texas can leverage current state programs to promote the equitable distribution of experienced and effective teachers. Recommendations include:

- Sustain and monitor the impact of teacher recruitment and retention efforts in HB3.

- Monitor implementation of the Teacher Incentive Allotment (TIA) to ensure evaluation systems are continuously improved for equity and reduce gaps in access to strong and diverse teachers, as already reported in the Texas Equity Plan.

- Sustain and monitor the impact of the Mentor Program Allotment included in HB3. Strengthen measurement and reporting requirements, including mentor and mentee demographic data.

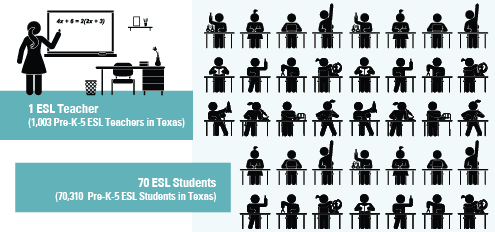

English learners are also being shortchanged. In Texas, there is a statewide shortage of bilingual/English as a second language (ESL) teachers, which prevents many English learners from having educators certified to teach the language acquisition and academic skills they need to excel.[25] In the 2019-2020 school year, English learners made up almost 20% of the Texas student body, but bilingual and/or ESL certified teachers remain a small portion, only 6% of the teacher workforce.[26]

In 2019, there were over 1 million English learner students in Texas, about half of which, 460,000 students, were in bilingual education programs and around 550,000 students were in ESL courses.[27] The majority of these students are young children in grades pre-K-5. For elementary school-aged English learners in ESL courses, there was only one elementary teacher for every 70 elementary ESL students (Figure 4). Also, 38% of Texas elementary schools (grades pre-K-5 and grade 6 when clustered with elementary grades) reported having no bilingual education program teacher, which equates to over 146,000 elementary age English learners attending schools without educators to teach bilingual programs designed for acquiring English proficiency.[28] This is unsustainable and results in many English learner students being placed in classrooms with out-of-field teachers who lack certification in the content, course, or grades they teach.

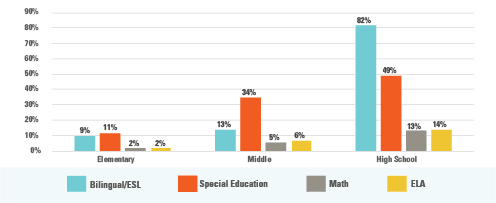

In the 2018-19 school year, bilingual/ESL courses had high percentages of out-of-field teachers when compared with other courses, particularly in high school (Figure 5). In fact, more than three-quarters of teachers in high school bilingual/ESL classrooms are out-of-field. Fifteen percent of all English learners in Texas are in high school grades.[29] How can we expect Texas’ English learner students to succeed if they lack access to the teachers trained to support them?

Also, half of high school teachers and a third of middle school teachers of students with disabilities don’t have the proper certification to support their learning needs. Access to a properly certified special education teacher is an important educational resource for students with disabilities to master grade-level content. The data show that the demand for Texas teachers with the knowledge and ability to teach special education, bilingual, and ESL courses remains unmet.

RECOMMENDATION: EXPAND THE PIPELINE OF FUTURE TEACHERS

There are teacher shortages across multiple content areas in Texas. Below are recommendations to address this challenge:

- Make targeted investments to help recruit and retain racially and linguistically diverse candidates in fields and communities that have a shortage of teachers, such as bilingual/ESL and Special Education.

- Expand the Teach for Texas Loan Repayment Assistance Program and other targeted financial aid and loan forgiveness for aspiring teachers.

- Prioritize resources for quality EPP programs recognized by TEA for preparing the educators Texas needs, especially minority-serving institutions that prepare a disproportionate number of aspiring teachers of color, along with those preparing teachers in rural areas and content shortage areas.

Texas is failing to provide equitable access to strong and diverse teachers for Black students, English learners, Latino students, students with disabilities, and students from low-income backgrounds. If the state does not expand its efforts to address this challenge, learning loss will be compounded for the state’s most vulnerable students.

TEXAS MUST INSTITUTE POLICIES NOW TO PREVENT INEQUITABLE EDUCATOR LAYOFFS AND GREATER TURNOVER.

When states make education budget cuts during economic downturns, it typically results in widespread staff layoffs or reductions in force (RIFs) because teacher salaries make up more than half of total school expenditures.[30] State revenue shortfalls disproportionately affect districts that rely most on state aid, which tend to serve large populations of students from low-income backgrounds and students of color.[31] As a result, schools and districts serving the most Black and Latino students and students from low-income backgrounds may bear the brunt of these layoffs.

During the Great Recession of 2008, almost 300,000 teachers and staff nationwide lost their jobs, and districts that served the most students from low-income backgrounds experienced an inequitable share of these staffing cuts.[32] This trend was also evident in Texas. Between 2008 and 2013, the wealthiest districts in Texas saw a 22% increase in the number of full-time teachers, while higher poverty districts experienced a 13% decline in the number of full-time teachers.[33] Evidence from the 2008 recession and the initial results of budget cuts related to COVID-19[34] also show that teachers of color are particularly vulnerable to layoffs, given that nationally, teachers of color are more likely to be novice[35] and they disproportionately teach in schools that serve students from low-income backgrounds.[36]

In the current economic situation, Texas must avoid replicating past patterns that negatively affected the state’s most underserved students. Reductions in state revenue could cost Texas more than 17,000 teachers.[37] Both ends of the teacher pipeline, recruitment and retention, could potentially shrink. But this does not have to be the case. Inequitable RIFs in the last recession led far more teachers to leave schools than was necessary to reach budget savings targets, and above all, hurt students by creating teacher churn and altering the quality composition of the teacher workforce.[38]

COVID-19 has created or exacerbated a number of challenges to ensuring that all students have access to strong and diverse teachers. The pandemic-induced recession may make preparation programs less accessible and affordable for those experiencing financial hardship. Schools may see higher turnover and vacancies if teachers consider leaving the profession because of the health risks and additional stressors of teaching in a pandemic. And districts that invested in efforts to diversify the educator workforce will likely be forced to reduce budgets, putting those efforts at risk.

PROTECTING EDUCATOR DIVERSITY AND EQUITY IN COVID-19 ERA

If the COVID-19 induced recession triggers education budget cuts, cuts to the highest need districts would undermine teacher diversity and equity in the state. Recommendations to shield the highest poverty districts from educator layoffs include:

- Ensure that districts do not disproportionately make staffing cuts (including layoffs and hiring freezes) to high-need schools.

- Shield the highest poverty districts from any state education funding cuts.

LEARNING FROM LOCAL SUCCESS: INCREASING EDUCATOR EQUITY IS POSSIBLE AND IT IMPROVES STUDENT OUTCOMES.

Accelerating Campus Excellence (ACE) is a model aimed at transforming struggling schools through effective leadership and teaching. Established in 2015, ACE attracts strong teachers to teach at the highest-need schools by providing incentives and resources to support school leaders and teachers.[39] ACE attracts school leaders and teachers with financial incentives ranging between $10K to $15K and retains them by cultivating professional learning communities among instructional staff. ACE schools are historically underperforming schools, serving mostly students from low-income backgrounds. Now, their students have greater access to excellent teaching. Over the first four years (2015-2019) of the ACE initiative, 28 of 29 campuses:

- Met state accountability standards in the first year, in most cases following multiple consecutive years of failure.

- Achieved increases in student growth upward of 67 percentage points in math and 40 percentage points in reading.

- Significantly reduced district gaps in achievement, discipline referrals and suspensions.[40]

ACE has been replicated across multiple districts in both elementary and middle schools. Scaling the success of the ACE initiative is one way that Texas can promote educator equity statewide.

TEXAS POLICYMAKERS MUST INSTITUTE POLICIES THAT ENSURE EQUITABLE ACCESS TO STRONG AND DIVERSE TEACHERS.

Data shows there is an urgent need to provide Black students, Latino students, English learners, and students from low-income backgrounds with strong and diverse teachers who can help them make up lost instructional time. Below are actions the state should take:

- As part of the Tri-Agency Workforce Initiative, set clear and numeric goals at the state, regional, and district level to increase access to strong and diverse teachers. Publicly report, monitor, and track progress toward these goals.

- Sustain and strengthen the state’s data systems, including Accountability System for Educator Preparation (ASEP), by collecting and publicly reporting (a) teacher retention rates by race at the state and district level, (b) teacher vacancy data at the state and district level, and ( c) candidate diversity at the EPP program-level within ASEP.

- Sustain and expand investment in GYO programs within the TEA ’s next strategic plan.

- Ensure recruitment and selection of racially and linguistically diverse candidates is a clearly articulated priority and establish common performance measures for all programs to report regularly.

- Establish regional consortiums to facilitate partnership between school districts, EPPs, and other community-based resources to design, implement, and sustain GYO strategies to meet local teacher workforce needs.

- Sustain and monitor the impact of teacher recruitment and retention efforts in HB3.

- Monitor implementation of the Teacher Incentive Allotment (TIA) to ensure evaluation systems are continuously improved for equity and reduce gaps in access to strong and diverse teachers, as already reported in the Texas Equity Plan.

- Sustain and monitor the impact of the Mentor Program Allotment included in HB3. Strengthen measurement and reporting requirements, including mentor and mentee demographic data.

- Especially during this difficult economic period, make targeted investments (similar to practices seen in ACE schools) to help recruit and retain racially and linguistically diverse candidates in fields and communities that have a shortage of teachers, such as bilingual/ESL and Special Education.

- Expand the Teach for Texas Loan Repayment Assistance Program and other targeted financial aid and loan forgiveness for aspiring teachers.

- Prioritize resources for quality EPP programs recognized by TEA for preparing the educators Texas needs, especially minority-serving institutions that prepare a disproportionate number of aspiring teachers of color, along with those preparing teachers in rural areas and content shortage areas.

- Ensure that districts do not disproportionately make staffing cuts (including layoffs and hiring freezes) to high-need schools.

- Shield the highest poverty districts from any state education funding cuts. If the COVID-19-induced recession triggers education budget cuts, cuts to the highest need districts would undermine teacher diversity and equity in the state. This must be prevented.

TARGETED POLICY ACTION CAN ENSURE TEXAS STUDENTS HAVE EQUITABLE ACCESS TO EDUCATORS NOW AND INTO THE FUTURE.

The effects of COVID-19 are vast and evolving. The full extent to which this pandemic will affect Texas’ students is not yet known. What we do know is that Texas needs to close gaps in access to strong and diverse teachers to begin to rectify decades of inequities and to combat the impact of this extended pause in in-person classroom instruction that disproportionately affects Black students, English learners, Latino students, and students from low-income backgrounds in Texas.

ENDNOTES

- Gershenson, Seth. (2016). Linking Teacher Quality, Student Attendance, and Student Achievement. Education Finance and Policy 2016, 11:2, 125-149. Available at: https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/full/10.1162/EDFP_a_00180 ; Jackson, Kirabo. (2016). What Do Test Scores Miss? The Importance of Teacher Effects on Non-Test Score Outcomes. NBER Working Paper. Available at: https://www.nber.org/papers/w22226#:~:text=Results%20show%20that%20teachers%20have,and%20on%2Dtime%20grade%20progression

- Strategic Data Project. (2015). SDP Educator Diagnostic: Delaware Department of Education. Center for Education Policy Research. Available at: https://cepr.harvard.edu/files/cepr/files/sdp-diagnostic-educatordelaware.pdf

- Kuhfeld, Megan, James Soland, Beth Tarasawa, Angela Johnson, Erik Ruzek, and Jing Liu. (2020). Projecting the potential impacts of COVID-19 school closures on academic achievement. Annenberg Institute at Brown University, EdWorkingPaper, 20-226. Available at: https://doi.org/10.26300/cdrv-yw05 ; Dorn, Emma, Hancock, Bryan, Sarakatsannis, Jimmy, and Viruleg, Ellen. (2020). COVID-19 and student learning in the United States: The hurt could last a lifetime. McKinsey & Company. Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/covid-19-and-student-learning-in-the-united-states-the-hurt-could-last-a-lifetime

- Ed Trust analysis of Texas Education Agency, Performance Reporting Division, 2018–19 Texas Academic Performance Report, STAAR Performance. Available at: https://rptsvr1.tea.texas.gov/perfreport/tapr/2019/srch.html?srch=S

- Ed Trust analysis of Texas Education Agency, Performance Reporting Division, 2018–19 Texas Academic Performance Report, STAAR Performance. Available at: https://rptsvr1.tea.texas.gov/perfreport/tapr/2019/srch.html?srch=S

- Hernandez-Nieto, Rosana, Gutierrez, Marcus C., and Moreno-Fernandez, Francisco. (2017). Hispanic Map of the United States, 2017. Instituto Cervantes at FAS- Harvard University. Available at: http://cervantesobservatorio.fas.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/hispanic_map_2017en.pdf

- Ed Trust analysis of United States Census Bureau, QuickFacts Texas, United States. (2019). All Topics. Available at: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/TX,US/PST045219 AND Texas Demographic Center. (2019). Texas Population Projections 2010 to 2050. Available at: https://demographics.texas.gov/Resources/publications/2019/20190128_PopProjectionsBrief.pdf

- Texas Education Agency, Enrollment Trends, Enrollment in Texas Public Schools 2018-19. Available at: https://tea.texas.gov/sites/default/files/enroll_2018-19.pdf

- The Education Trust. (2019). 5 Things to Advance Equity in Access to Strong and Diverse Educators. Available at: https://edtrust.org/resource/5-thingsto-advance-equity-in-access-to-strong-and-diverse-educators/

- The Education Trust. (2019). 5 Things to Advance Equity in Access to Strong and Diverse Educators. Available at: https://edtrust.org/resource/5-things-to-advance-equity-in-access-to-strong-and-diverse-educators/; Holt and Gershenson. (2015) “The Impact of Teacher Demographic Representation on Student Attendance and Suspensions.” Gershenson, Hart, Lindsay, Papageorge. (2017). “The Long-Run Impacts of Same-Race Teachers.” ; Dee, Thomas. (2004) “Teachers, Race, and Student Achievement in a Randomized Experiment. Review of Economics and Statistics,” ; Egalite, Kisida, and Winters. (2015). “Representation in the classroom: The effect of own-race teachers on student achievement,”; Klopfenstein. (2005). “Beyond Test Scores: The Impact of Black Teacher Role Models on Rigorous Math Taking,”

- Ed Trust analysis of Texas Education Agency, Performance Reporting Division, 2018–19 Texas Academic Performance Report. Campus. Profile: Staff, Student, Annual Graduates. (2019). Available at: https://rptsvr1.tea.texas.gov/perfreport/tapr/2019/download/DownloadData.html

- Ed Trust analysis of Texas Education Agency, Performance Reporting Division, 2018–19 Texas Academic Performance Report. Campus. Profile: Staff, Student, Annual Graduates. (2019). Available at: https://rptsvr1.tea.texas.gov/perfreport/tapr/2019/download/DownloadData.html

- Kini, Tara, and Podolsky, Anne. (2016). Does Teaching Experience Increase Teacher Effectiveness? A Review of the Research. Learning Policy Institute. Available at: http://mrbartonmaths.com/resourcesnew/8.%20Research/Improving%20Teaching/Teaching%20Experience.pdf

- Texas Education Agency. (2019). Texas Equity Toolkit. State Equity Reports. Available at: https://texasequitytoolkit.org/Home/reports ; Texas Education Agency. (2015). State Plan to Ensure Equitable Access to Excellent Educators Submitted to the U.S. Department of Education. 2015 Texas

Equity Plan. Available at: https://www2.ed.gov/programs/titleiparta/equitable/texasequityplan080715.pdf ; *”Inexperienced” refers to teachers with less than one year of teaching experience. - Ed Trust analysis of Texas Education Agency, Texas Academic Performance Reports, 2018-19 TAPR Advanced Data Download. Campus. Profile: Staff, Student, and Annual Graduates. Available at: https://rptsvr1.tea.texas.gov/perfreport/tapr/2019/download/DownloadData.html

- Ed Trust analysis of Texas Education Agency, Texas Academic Performance Reports, 2018-19 TAPR Advanced Data Download. Campus. Profile: Staff, Student, and Annual Graduates. Available at: https://rptsvr1.tea.texas.gov/perfreport/tapr/2019/download/DownloadData.html

- Templeton, Toni, Lowrey, Sherri, Horn, Catherine L., Alghazzawi, Dina, and Bui, Binh. (2020). Assessing the Effectiveness of Texas Educator Preparation Programs. University of Houston, College of Education.

Available at: https://uh.edu/education/research/institutes-centers/erc/reports-publications/deans-report-epp-july-2020.pdf - Templeton, Toni, Lowrey, Sherri, Horn, Catherine L., Alghazzawi, Dina, and Bui, Binh. (2020). Assessing the Effectiveness of Texas Educator Preparation Programs. University of Houston, College of Education.

Available at: https://uh.edu/education/research/institutes-centers/erc/reports-publications/deans-report-epp-july-2020.pdf - Templeton, Toni, Lowrey, Sherri, Horn, Catherine L., Alghazzawi, Dina, and Bui, Binh. (2020). Assessing the Effectiveness of Texas Educator Preparation Programs. University of Houston, College of Education.

Available at: https://uh.edu/education/research/institutes-centers/erc/reports-publications/deans-report-epp-july-2020.pdf

- Ed Trust analysis of Texas Education Agency, State Board of Educator Certification. (2020). Newly Certified Teacher Demographics by Preparation Route 2014-15 through 2018-29. Available at: https://tea.texas.gov/sites/default/files/Newly%20Certified%20Teacher%20Demographics%20by%20Preparation%20Route%202014-15%20through%202018-19.pdf

- Templeton, Toni, Lowrey, Sherri, Horn, Catherine L., Alghazzawi, Dina, and Bui, Binh. (2020). Assessing the Effectiveness of Texas Educator Preparation Programs. University of Houston, College of Education.

Available at: https://uh.edu/education/research/institutes-centers/erc/reports-publications/deans-report-epp-july-2020.pdf - Texas Education Agency. Accountability System for Educator Preparation. Available at: https://tea4avcastro.tea.state.tx.us/ELQ/educatorprepdatadashboard/asepoverview.html

- Teacher Incentive Allotment. Texas Education Agency. Available at: https://tiatexas.org/about-teacher-incentive-allotment/

- Teacher Incentive Allotment. Press Release. A Signature Part of HB 3, in its Inaugural Year, the Teacher Incentive Allotment Will Benefit More than 3,600 Texas Teachers. (2020). Available at: https://tiatexas.org/tiainaugural-year-benefits/

- Texas Education Agency. 2020-2021 Teacher Shortage Areas and Loan Forgiveness Programs. (2018). Available at: https://tea.texas.gov/abouttea/news-and-multimedia/correspondence/taa-letters/2020-2021-teachershortage-areas-and-loan-forgiveness-programs

- Ed Trust analysis of Texas Education Agency, Snapshot 2019: Summary Tables, State Totals. Available at: https://rptsvr1.tea.texas.gov/perfreport/snapshot/2019/state.html

- Texas Education Agency, PEIMS Standard Reports, English Learner (EL) Students by Category and Grade. (2018-2019). Available at: https://rptsvr1.tea.texas.gov/adhocrpt/adlepcg.html

- Ed Trust analysis of Texas Education Agency, Texas Academic Performance Reports, 2018-19 TAPR Advanced Data Download. Campus. Profile: Staff, Student, and Annual Graduates. Available at: https://rptsvr1.tea.texas.gov/perfreport/tapr/2019/download/DownloadData.html; TX §89.1201. Policy. Available at: http://ritter.tea.state.tx.us/rules/tac/chapter089/ch089bb.html ; Districts are only required to offer bilingual education programs for English learners in prekindergarten through the elementary grades with that language classification. “Elementary grades” shall include at least prekindergarten through Grade 5; sixth grade shall be included when clustered with elementary grades. The analysis excludes schools grades higher than 6, and combination schools that cluster elementary grades with grades 7 or higher (i.e. K – 12 schools, PK – 8 schools, etc.).

- Ed Trust analysis of Texas Education Agency, PEIMS Standard Reports, English Learner (EL) Students by Category and Grade. (2018-2019). Available at: https://rptsvr1.tea.texas.gov/adhocrpt/adlepcg.html

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2020). Public School Expenditures. Available at: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cmb.asp

- Burnette II, Daarel. (2020). Devastated Budgets and Widening Inequities: How the Coronavirus Collapse Will Impact Schools. Education Week. Available at: https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2020/05/09/devastated-budgets-and-widening-inequities-how-the.html

- Knight, D.S. (2017). Are High-Poverty School Districts Disproportionately Impacted by State Funding Cuts?: School Finance Equity Following the Great Recession. Journal of Education Finance 43(2), 169-194. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/688011/pdf

- Knight, David S. (2016). Were High-Poverty Districts in Texas Disproportionally Impacted by State Funding Cuts? School Finance Equity in Texas Following the Great Recession. Center for Education Research and Policy Studies, College of Education. University of Texas at El Paso. Policy Brief #1. Available at: https://www.utep.edu/education/cerps/_Files/docs/briefs/Policy_Brief1_TX_School_Finance.pdf

- Schuster, Christine. (2020). Award-winning teachers of color lost to budget cuts in Burnsville call for introspection, policy change. SWnewsmedia. Available at: https://www.swnewsmedia.com/savage_pacer/news/education/award-winning-teachers-of-color-lost-to-budget-cuts-inburnsville-call-for-introspection-policy/article_a83023c4-a222-5133-8426-5c7ed8aa4bfa.html

- National Center for Education Statistics. Digest of Education Statistics. (2019). Number, highest degree, and years of teaching experience of teachers in public and private elementary and secondary schools, by

selected teacher characteristics: Selected years, 1999-2000 through 2017-18. Table 209.20. Available at: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_209.20.asp - Carver-Thomas, Desiree, and Darling-Hammond, Linda. (2017). Teacher Turnover: Why It Matters and What We Can Do About It. Learning Policy Institute. Available at: https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Teacher_Turnover_REPORT.pdf

- Griffith, Michael. (2020). The Impact of the COVID-19 Recession on Teaching Positions. Learning Policy Institute, Blog. Available at: https://earningpolicyinstitute.org/blog/impact-covid-19-recession-teachingpositions

- Goldhaber, Dan, Strunk, Katharine O., Brown, Nate, and Knight, David S. (2015). Lessons Learned From the Great Recession: Layoffs and the RIFInduced Teacher Shuffle. CALDER Working Paper No. 129. Available at: https://caldercenter.org/sites/default/files/WP%20129.pdf

- Dallas Independent School District. Accelerating Campus Excellence (ACE). About. Available at: https://www.dallasisd.org/Page/46765

- Best In Class Coalition. ACE – Introduction. Available at: http://bestinclass.org/ace-introduction/

November 10, 2020 by

November 10, 2020 by