Jim Crow Debt

Student debt has been a crisis for years, and the pandemic has only exacerbated matters for many borrowers. This is especially true for Black borrowers, who are among those most negatively affected by student loans.

How Black Borrowers Experience Student Loans

Student debt has been a crisis for years, and the pandemic has only exacerbated matters for many borrowers. This is especially true for Black borrowers, who are among those most negatively affected by student loans — due, in large part, to systemic racism, the inequitable distribution of wealth in this country, a stratified labor market, and rising college costs. And whether by willful intent or gross negligence, many of those engaged in this policy debate overlook the compounding effect of racism and how it specifically impacts Black borrowers. Put simply, student debt is a racial and economic justice issue, and any proposed solution to the student debt crisis must center the perspectives, lived realities, and voices of Black borrowers, rather than solely use their data to frame the problem.

That is why in 2020, in partnership with Jalil B. Mustaffa, Ph.D., we launched the National Black Student Loan Debt Study. This study is based on a nationwide survey of nearly 1,300 Black borrowers and in-depth interviews with 100 Black borrowers across various life points. Rather than reporting student loan outcomes, we focus on borrowers’ perspectives and life experiences with student loans.

In Jim Crow Debt: How Black Borrowers Experience Student Loans, we share the stories we heard, so we can learn from the Black borrowers’ experiences.

In this study, we employed a sequential, equal status mixed-method design with a non-random sampling scheme. We designed and created a survey instrument that elicited Black borrowers’ perspectives on student loans and their experiences with them — paying particular attention to their mental health, the quality and sources of information, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, borrowers’ return on investment, debt as a contributor to inequality, and Black borrowers’ solutions to the current debt crisis. In total, 1,272 Black borrowers completed our survey. Our survey sample consists largely of four-year and graduate degree holders, women, borrowers aged 25 and older, and borrowers earning $50,000 or more annually.

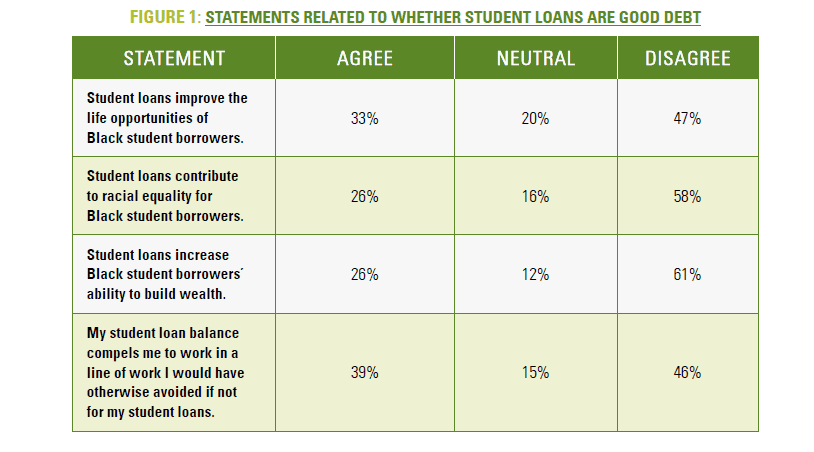

Student loan debt is widely considered “good debt” as it offers a pathway to obtaining credentials that can lead to higher incomes, greater wealth, and social mobility. For Black borrowers, however, these gains have never been equal and are continuously undercut. In our study, Black borrowers, even those with higher incomes and graduate degrees, challenged the assumption that student loans pay off. Black student loan borrowing is driven by a desire for higher-paying jobs and a better life.

“I knew that we did not have money in my household. I knew that we struggled to make ends meet. I knew that it was totally bizarre for someone my age [I was 19 years old at the time] to sign a check for an amount of money that I had never held in my hand, and for it to go to the school.”

– Lisa (who borrowed $115,000)

But since a costly higher education is a prerequisite for those jobs, borrowers often find themselves in a catch-22, according to many of those we interviewed. More than half of the Black borrowers in our study said they do not believe that student loans advance racial equality for Black borrowers (58%) or increase Black borrowers’ ability to build wealth (61%) and 66% regret having taken out education loans that now seem “unpayable” and “not worth it.”

“I have worked at a nonprofit for 27 years and have tried to work with my multiple loan servicers to get public service forgiveness. I only get the run around … I tried the Department of Education, my congressmembers. I am 62 years old and do not know how I will retire.”

– Georgia (who borrowed $24,000 in 1990; and owes $125,000 today)

In the policy arena, a solution that is routinely offered as an alternative to large-scale student debt cancellation is reforming income-driven repayment (IDR) plans. The plans work as follows: Borrowers apply to enroll and, if they qualify, their monthly student debt payment is adjusted based on their discretionary income, and the standard 10-year repayment period is extended over 20-25 years — at which point, they can apply to have their outstanding student loan balance cancelled.

Of the Black borrowers in our study who were in repayment, 72% were enrolled in an IDR plan. In interviews, many of them described their student loans as a “trap” or “scam” or drew comparisons between their experiences in these plans and historic examples of racial oppression. Many also described student loans as a lifetime sentence, in which they “do their time,” re-enroll in IDR every year, but have no “hope of paying off their balance.” They described their growing balances under IDR plans as “shackles on their ankle” or “like Jim Crow,” where the debt ensures that they will never have full freedom.

Finding #3: Limiting student debt cancellation would harm Black borrowers the most

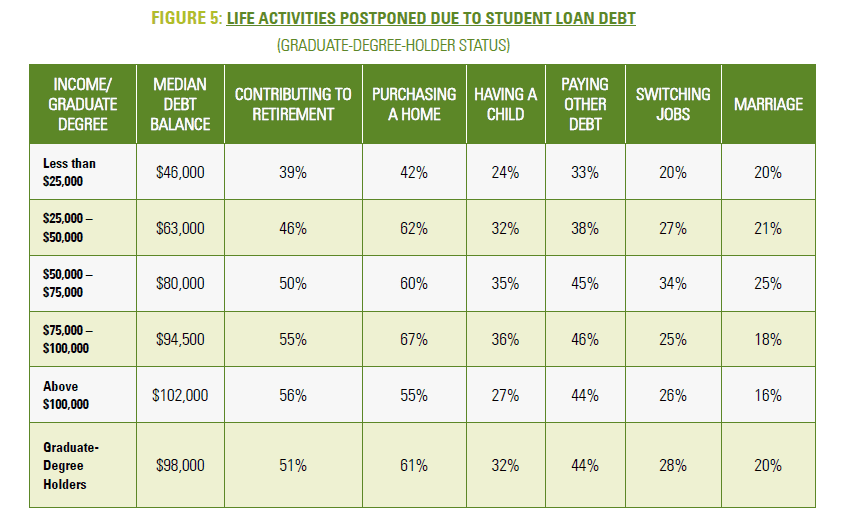

Much of the student debt cancellation debate has focused on who should and should not receive cancellation, with many policy proposals calling for limiting (i.e., means-testing) cancellation by income, graduate school debt, and/or amount borrowed. Using income and graduate degrees as markers of economic wellness assumes that all racial groups have access to the same financial means and opportunities, but decades of research show that Black people have vastly different economic experiences, due to structural racism that has limited and stolen wealth from Black families.

“I wish something would be different … that students [were] not punished for not wanting to live in poverty. I say that because it’s like when you’re in grad school, they want you to get these experiences through internships, through real world practice, but then when you do it and [want] somebody to pay you for it, it’s like you’re punished.”

– Dae (who borrowed $35,000)

Graduate programs usually prohibit students with scholarships and fellowships from working full time or require them to take on unpaid internships, field work, and course loads that make full-time employment a non-option. As a result, many borrowers must borrow, not just for tuition and fees, but also to cover necessary living expenses. Contrary to popular belief, having a graduate degree and a higher income did not mean these Black borrowers were off to the races. It got them a delayed start behind those with degrees and no debt and left them with little hope of ever catching up.

“I mean, realistically, I think the [student loan] system is working exactly as we expect it to. Like, it was designed for this very outcome and so no one’s surprised that we somehow built a financial aid process and policy and set that up to only consider your annual salary, as if [Black people] all have the same net assets.”

– Leonard (who borrowed $205,000)

Since Black borrowers are most heavily impacted by the student debt crisis, their views on solutions must be a central consideration in any conversation or proposal on how to address the crisis. If policymakers and advocates hope to understand the full depth of the crisis and identify a path forward that will right ongoing racial wrongs, they must listen to and lead with Black people’s voices.

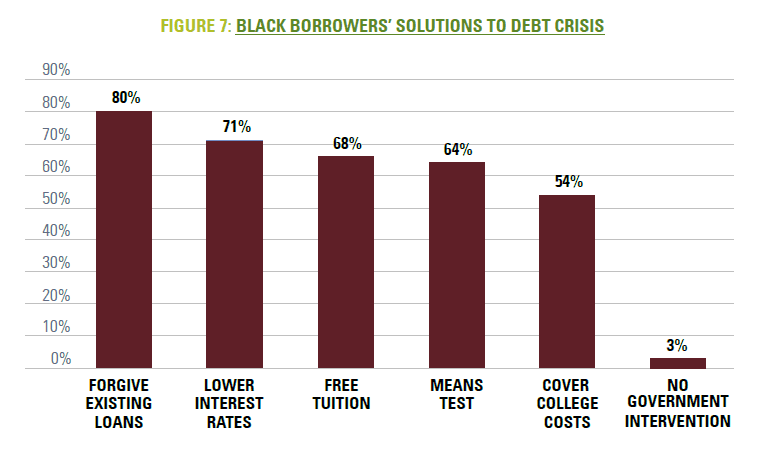

In our study, Black borrowers noted that a system that encourages the use of student loans and ignores racial and economic evidence of inequality is designed to reproduce inequality. They also insisted that there are potential solutions that reflect alternative policy frames for racial justice. For instance, 80% of the Black borrowers we surveyed support government forgiveness of all student debt — in fact, participants backed this solution more than any other. In contrast, only 3% of them oppose government intervention in student debt repayment. For many of those surveyed, debt cancellation was a matter of racial justice.