High-Quality Materials

Most elementary schools teach reading with either a basal reading program, a teacher-developed curriculum, or a balanced literacy program like Fountas & Pinnell or Teachers College Units of Study.

But the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO), in calling for a national improvement in reading instruction, has called upon all state superintendents and commissioners to encourage schools and districts to adopt the high-quality materials that have been developed in the last few years to line up with both Common Core state standards and with the science of reading.

In this episode, experts Carol Jago and David Liben talk with Ed Trust’s director of practice Tanji Reed Marshall and writer-in-residence Karin Chenoweth about the difference using high-quality materials at both the elementary and secondary levels could make in helping students learn to read.

Jago is a longtime English teacher and a former president of the National Council of Teachers of English, as well as a prolific writer, including a widely used high school English textbook. She has been awarded several career awards, such as the International Literacy Association’s Adolescent Literacy Thought Leader Award. Liben, also a longtime teacher, was deeply involved in the development of state standards for reading and has served as a consultant in the development of several of the English Language Arts curricula which are considered “high quality.”

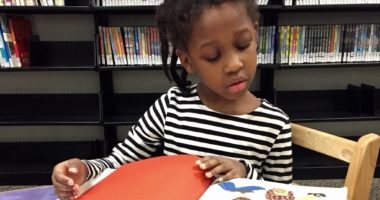

“When I go around to schools using one of these high-quality materials,” Liben said, “the teachers almost always say they never thought their struggling readers would be this involved in what they’re doing.” The reason, Liben said, is the bulk of the day is spent on rich grade-level texts so that even the weakest readers are “Playing in the ball-game. They’re part of it.”

Liben said that too often when people talk about the “science of reading” they are simply talking about teaching phonics. That is important to teach, he said. But he talked about the need to understand additional sciences—of vocabulary development, building background knowledge, mastering features of complex text, and standard of coherence—to have a more integrated understanding of reading science. In addition, when students write about what they read, Jago said, not only do they clarify their own thoughts but they also provide a “window” for their teachers to understand what young learners are understanding. That helps teachers to “craft instruction in response to that.”

“The National Reading Project,” she said, has been helpful in showing teachers how to better teach and assess writing. (Chenoweth mentioned a project in the UK that is working to help teachers assess writing with something called “comparative judgment.”)

The elementary programs that Liben, Jago, and Marshall consider to be “high quality” are Great Minds’ Wit and Wisdom*; EL Education; Core Knowledge; American Reading Company; and Bookworms. At the secondary level, Jago said, most teachers continue to teach novels and said English teachers need to help their students “interrogate” the novels they teach rather than stop teaching them because of problematic content. She also mentioned that Student Achievement Partners had brought in the organization Disrupt Texts to help think about how teachers can expand their understanding and skill of how to do that. She said that the American Indians in Children’s Literature website has been helpful in her expanding her understanding of the way American Indians have been portrayed in children’s literature.

In addition, Marshall mentioned a new study about the positive effect social studies instruction has on reading ability. And Chenoweth noted that Bookworms is featured in Season 2, Episode 4 of ExtraOrdinary Districts, which is a profile of Seaford, Delaware.

* In Season 3, episode 18, Baltimore City Superintendent Sonja Santelises said that her city had adopted Wit and Wisdom but had also developed a supplementary curriculum because the African American experience is not well represented in the program.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | RSS