Learning Honest History Isn’t Criminal — It’s What Students Deserve to Know

Amid the debate surrounding so-called Critical Race Theory (CRT), Republican lawmakers in 37 states have introduced legislation or taken significant steps to limit an educator’s ability to discuss race and bias in the classroom. In Virginia, of which I am a native son, Governor Glenn Youngkin, on his first day in office, signed an executive order banning “divisive concepts, including Critical Race Theory in schools” (of which there is none in P-12). He also set up a tip line for parents to report teachers who promote “divisive practices in the classroom,” a statewide policy which one Black Virginia history teacher claimed was “scaring people to death.”

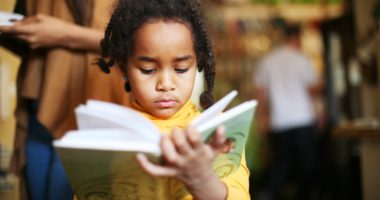

In addition to the harms caused to educators, these anti-CRT legislative efforts could have a devastating impact on students. In our ever-changing and interconnected world, it is more important than ever that younger generations develop the critical thinking skills necessary to digest our complex history in the context of current events. Without these critical skills, how can our nation’s future leaders identify and dismantle systems of oppression? Parents and teachers need to work together to help students learn that while this nation has made great strides, it still has a long way to go to form a more perfect union. It’s important that students of color see themselves in the curriculum, so they can participate in their education in a meaningful way. And White students in turn can learn how people who are different than themselves feel, how to better understand inequality in society today, and develop skills to address these problems. I know that worked for me — albeit latently.

My own understanding of my home state’s history was at best incomplete, at worst embarrassingly naïve. It wasn’t until I took a “Virginia Government and Politics” course at the University of Virginia that I learned about significant historical events that shaped not only the Commonwealth’s current political, economic, and social structure, but also that of the entire country, including:

- Born to enslaved parents in Richmond during the Civil War, Maggie Lena Walker would become the first woman of any race to establish and run a bank in the United States. The St. Luke Penny Savings Bank not only greatly expanded the public role of women nationally, but it also established Richmond as a bastion of African American enterprise known as “Black Wall Street.”

- At age 16, Barbara Johns led her fellow Black students in a two-week strike protesting segregated schools in her community in 1951. A lawsuit was subsequently filed which would eventually become part of the groundbreaking 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Brown v. Board of Education.

- Lawrence Douglas Wilder, whose grandparents were enslaved, became the first elected African American governor in United States history as Virginia’s 66th governor in 1990. Before that, Wilder was elected to the Virginia State Senate in 1969, serving as the state’s first Black state senator since Reconstruction.

These stories and more were instances of remarkable perseverance and bravery; they are stories that deserve and need to be told. But all I could think about was how so much of this information was new to me. How could I be so blissfully ignorant to the history of my own state and community? How could so much important, local history be omitted from my public education? The experiences of communities of color in Virginia was in many ways ignored throughout my elementary and secondary education. This realization left me not only frustrated at my own white ignorance, but also angry and disheartened for my former classmates of color who were robbed of the opportunity to see themselves in the lessons being taught.

These actions by the right are part of a larger national and politically driven effort to deny the systemic racism that continues to permeate society today as well as a knee-jerk reaction to the changing demographics of our country. Either way, the children are doomed to suffer at the hands of close-minded adults. Every student is entitled to a rich, complete, and culturally responsive education. This is about telling the true history of America, not just the good, but the bad as well. This is about creating classrooms where everyone feels valued and accepted, regardless of race, ethnicity, gender identity, or religion. This is how we get to a better America — not by sweeping large swaths of our history and culture under the proverbial rug — but with honesty, empathy, and justice for all.