What’s Behind the Teacher Strikes? A Look at Teacher Salaries

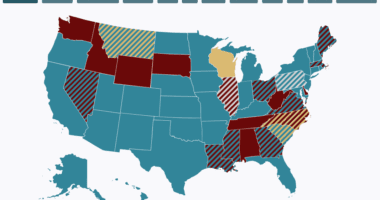

The school year may have come to a close, but for some teachers across the country, things are just getting started. From North Carolina to Arizona, teachers have been making headlines for strikes and “sick-outs,” which are expected to ramp up in other states next school year. While specific concerns vary, the common thread has been under-investment in teachers, resources, and in public education in general. Data show not only the validity of their concerns, but that teacher salaries in the states where teachers are protesting (Arizona, Colorado, Kentucky, North Carolina, Oklahoma, and West Virginia) reflect troubling patterns in education spending writ large.

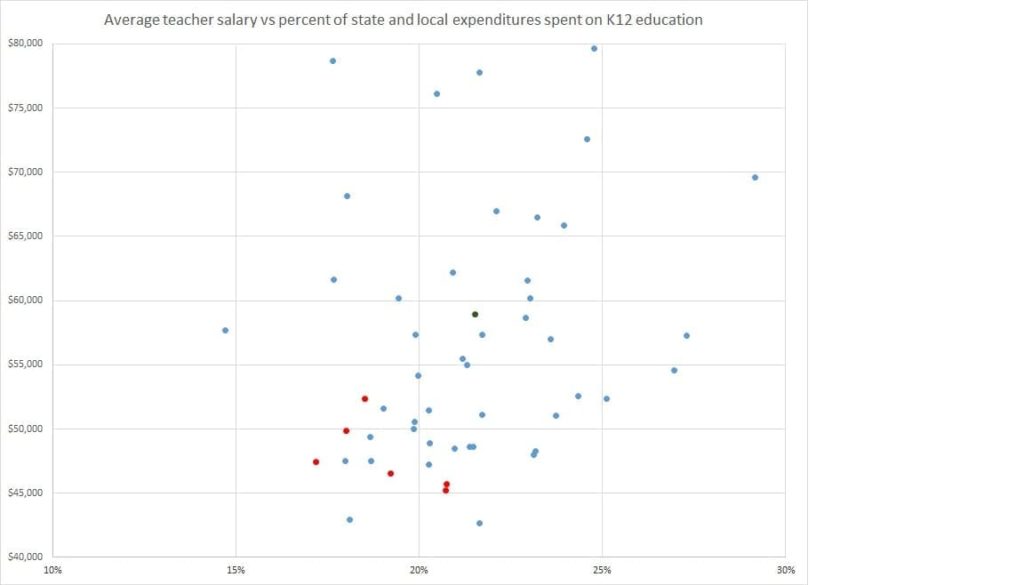

Many states should be investing more in public school teachers. But teachers who are protesting are especially underpaid. In Oklahoma, for example, the average teacher makes $45,245 compared to $52,575 in neighboring Texas. Meanwhile, the national average for teacher salaries is $58,950. These salary disparities reflect, in part, huge variations in school funding from place to place, with low funding especially glaring in states where teachers are protesting. For example, Arizona spends 22 percent less per student than neighboring New Mexico: $7,590 versus $9,724. Underinvestment in education hurts all students, but it’s especially damaging for students from low-income families, who see the greatest benefits from increased education spending.

What’s more, it’s not necessarily that these six states have less money to spend (though in some states like West Virginia, that’s a real concern), but rather that state and local leaders are choosing to invest a lower percentage of their overall budgets in K-12 education.

As the chart shows, in the states with teacher protests (in red) state and local leaders spend less of their budgets on K-12 education than the national average (in dark green).

Source: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d17/tables/dt17_211.60.asp and http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/statistics/state-and-local-general-expenditures-capita

Of course, teachers enter the classroom not just for money but because they want to do good. And we at Ed Trust know that, even more than salary, the presence of strong leadership and collaborative cultures are the factors most likely to keep teachers at their school. But even the best working conditions are not a substitute for reasonable wages — ones that are competitive with opportunities for individuals with similar levels of education and that, at minimum, allow teachers to sustain themselves and their families.

What’s more, while it’s possible to create positive working conditions for teachers even when money is short, it’s easier when there’s enough funding. After all, practices that have been shown to develop and retain strong school teachers, like compensating master teachers for leading teams of teachers and rewarding expert principals for mentoring new principals on instructional leadership, cost money.

State leaders and legislators often talk about education being the great equalizer, and pay lots of lip service to the importance of teachers. But if state leaders want to improve educational opportunity for all students — but especially students from underserved communities, who need high-quality schools and the strongest teachers the most — they have to back up that rhetoric with tangible resources, and that starts with funding.