More Intersections: Why We Need Afro-Latino Representation in Children’s Books

Latinos deserve to have books to which they can relate and aspire. Non-Latinos should learn about rich, diverse cultures.

“What ARE you?” That was the number one question I was asked growing up. Several decades ago, the only reference point most Californians had for Latinos was Mexico, and with my curly hair, olive skin, dark eyes, and African American features, I didn’t fit the description. Was I a light-skinned Black girl? Maybe. Basically, back then, no one really knew what a Puerto Rican was. To be honest, I didn’t either.

As a child, I was a voracious reader, gobbling up books by Judy Blume, Beverly Cleary, and Roald Dahl. While I adored these authors and their stories, there was something that I just couldn’t fully relate to in characters like Deenie, Ramona, or James (though I do love peaches). And 20-something years later, after I had returned to my Nuyorican roots and later became a mom, I found that not much had changed in the literary world: Almost all the children’s books I sought out for my child centered whiteness — with the exception of the occasional adorable animal, like Olivia the pig.

As a writer, I wanted to change that.

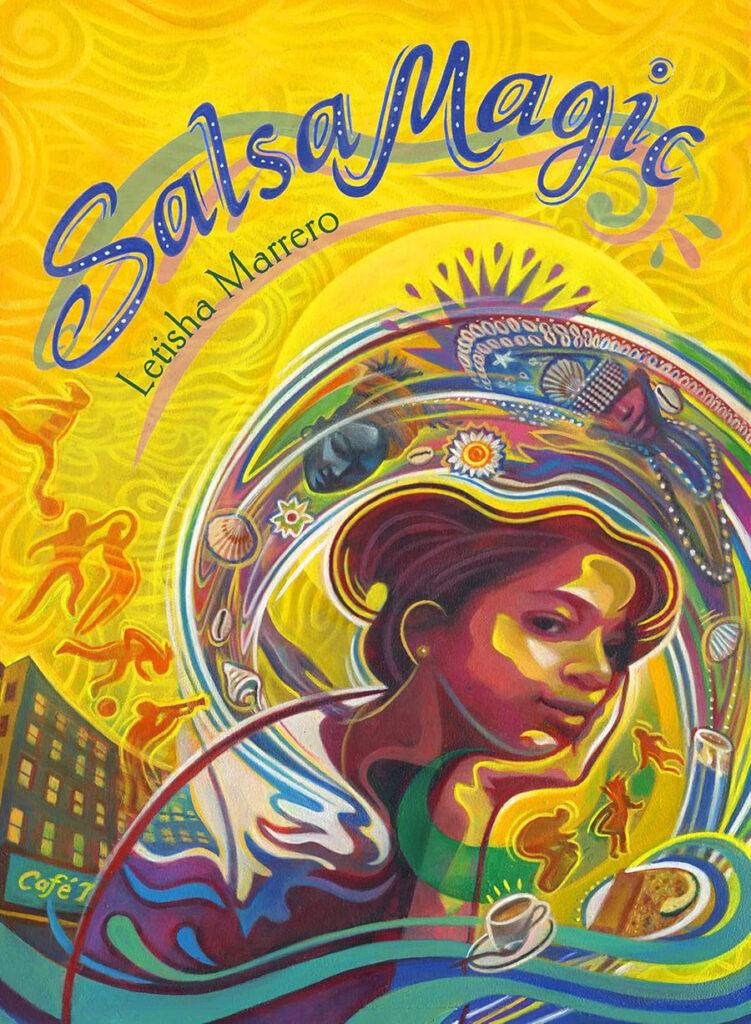

When coming up with a story, I usually start with the question, “What if?” So, after my son became obsessed with the World of Hogwarts, I asked myself, “What if Harry Potter were Latina?” That spawned my middle-grade novel, Salsa Magic. My main character, Maya Beatriz Calderon Montenegro, is Afro-Latina and Mexican — two cultures I straddled between as a kid in San Diego and an adult in New York City. She is everything that I wanted to be as a child: brave, pretty, confident, precocious, and sassy. She comes from a loud, loving Latino family who own a bustling café — and many of those characters were inspired by my myriad first, second, and third cousins in New York.

When coming up with a story, I usually start with the question, “What if?” So, after my son became obsessed with the World of Hogwarts, I asked myself, “What if Harry Potter were Latina?” That spawned my middle-grade novel, Salsa Magic. My main character, Maya Beatriz Calderon Montenegro, is Afro-Latina and Mexican — two cultures I straddled between as a kid in San Diego and an adult in New York City. She is everything that I wanted to be as a child: brave, pretty, confident, precocious, and sassy. She comes from a loud, loving Latino family who own a bustling café — and many of those characters were inspired by my myriad first, second, and third cousins in New York.

I wanted young Latinos to have characters to whom they could relate and aspire. And I wanted non-Latinos learn about a rich, diverse culture different than their own, but that is still relatable with universal ties to family and all the beautiful mess that comes with it.

Afro-Latinidad is its own category — representing 12% of the Latino population. And in fact, the Office of Management and Budget has recently made changes to the way that all federal agencies collect race and ethnicity data, in hopes of making it easier for groups like Afro-Latinos to report their race AND Hispanic/Latino ethnicity. Our identity is unique because of our roots: After “discovering” the Caribbean islands (which had been inhabited for 4,000 years prior), the Spanish colonizers decimated the native Taíno, and brought with them enslaved people from Africa to work the land and would then take the riches back to Spain. This was known as the Triangle Trade System. As such, Puerto Ricans and Dominicans are a blend of Spanish, Taíno, and African blood — in varying degrees. Among this mestizaje, there is a not-so-silent caste system, where lighter skin is revered, and darker skin is considered a detriment. In Salsa Magic, I purposely describe different characters with different skin tones — from café con leche to trigueño (wheat) — to showcase the diversity among Afro-Latinos, even within one’s own family. Additionally, I describe an array of body types, from bien mujer (womanly) to bien gordita (good chubby) and flaca (skinny). You’ll also read about varied hair textures— loose curls, tight curls, Afros, braids and blowouts. These are all part of the diaspora and show that Latinos are anything but a monolith.

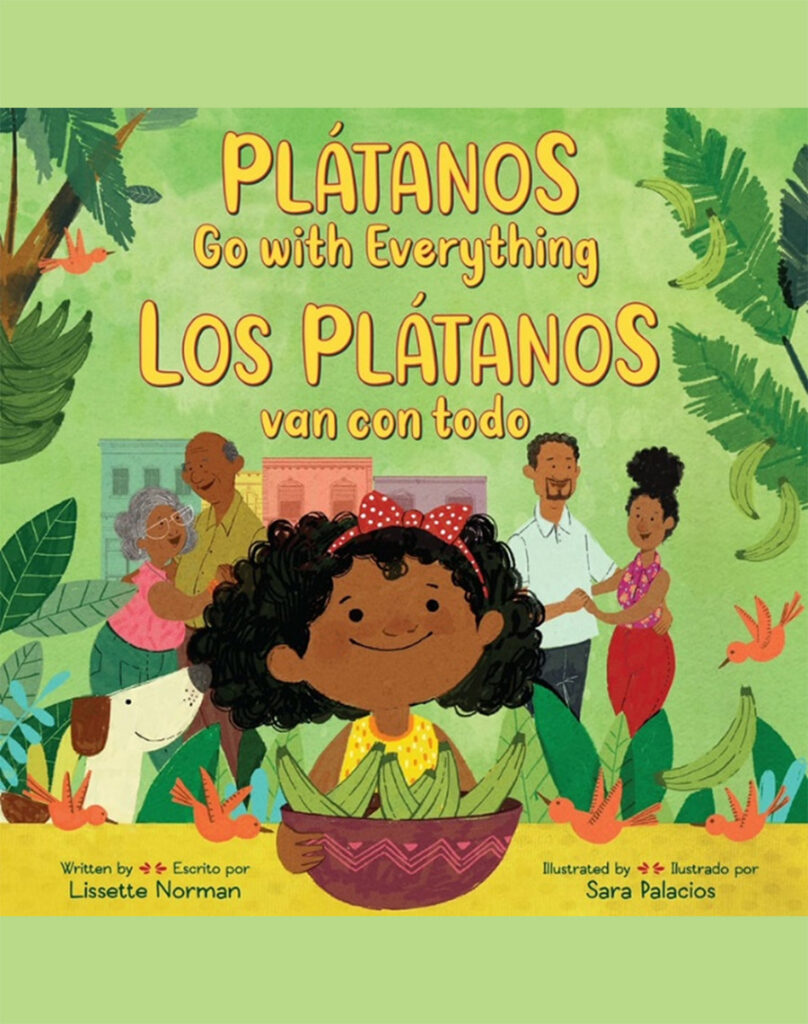

When we talk about racial and cultural representation in children’s books, publishers and educators need to know that there must be authentic experiences in reading materials that are relatable to children in order to be effective and have meaning as they learn to read. A child being able to say something like, “My abuela is just like that!” or “I love platanos too!” is a powerful statement and feeling. And I’ve seen this effect firsthand: on one school visit, the sole Latina at an all-Black girl grade school lit up when I was reading aloud, like I was speaking just to her. And the Black girls relished when the time came to salsa dance to the sounds based on the African beat, known as el clave. I got just as much out of the girls as they did of me — because that’s what representation not only looks like, but acts like.

Each piece in this series is accompanied by relevant resources and book recommendations provided by one of our partners, with input from the authors.

Las Musas

In addition to being the author of Salsa Magic, Letisha Marrero is EdTrust’s editorial director, and a member of Las Musas, a collective of Latina women and otherwise marginalized people whose gender identity aligns with femininity, writing and/or illustrating in traditional children’s literature. Their mission is to spotlight the new contributions of Las Musas in the evolving canon of children’s literature and celebrate the diversity of voice, experience, and power in our communities. Lasmusasbooks.com features a wide variety of young adult, middle-grade, and picture books written or illustrated by Latina authors for you to explore.