The United States is home to more than 400,000 undocumented students in higher education, including 181,000 Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA)-eligible students. This means that one out of every 50 students in college is undocumented. Unlike other college students, however, undocumented students must often navigate complex rules and regulations to access a higher education — solely on account of their immigration status. Everyone should have the opportunity to pursue a postsecondary education. There is an urgent need to eliminate barriers to higher education for undocumented students and create opportunities to help launch their professional careers. States and institutions should support inclusive policies that increase undocumented student access to higher education — including in-state tuition and state financial aid eligibility for these students — instead of blocking their enrollment.

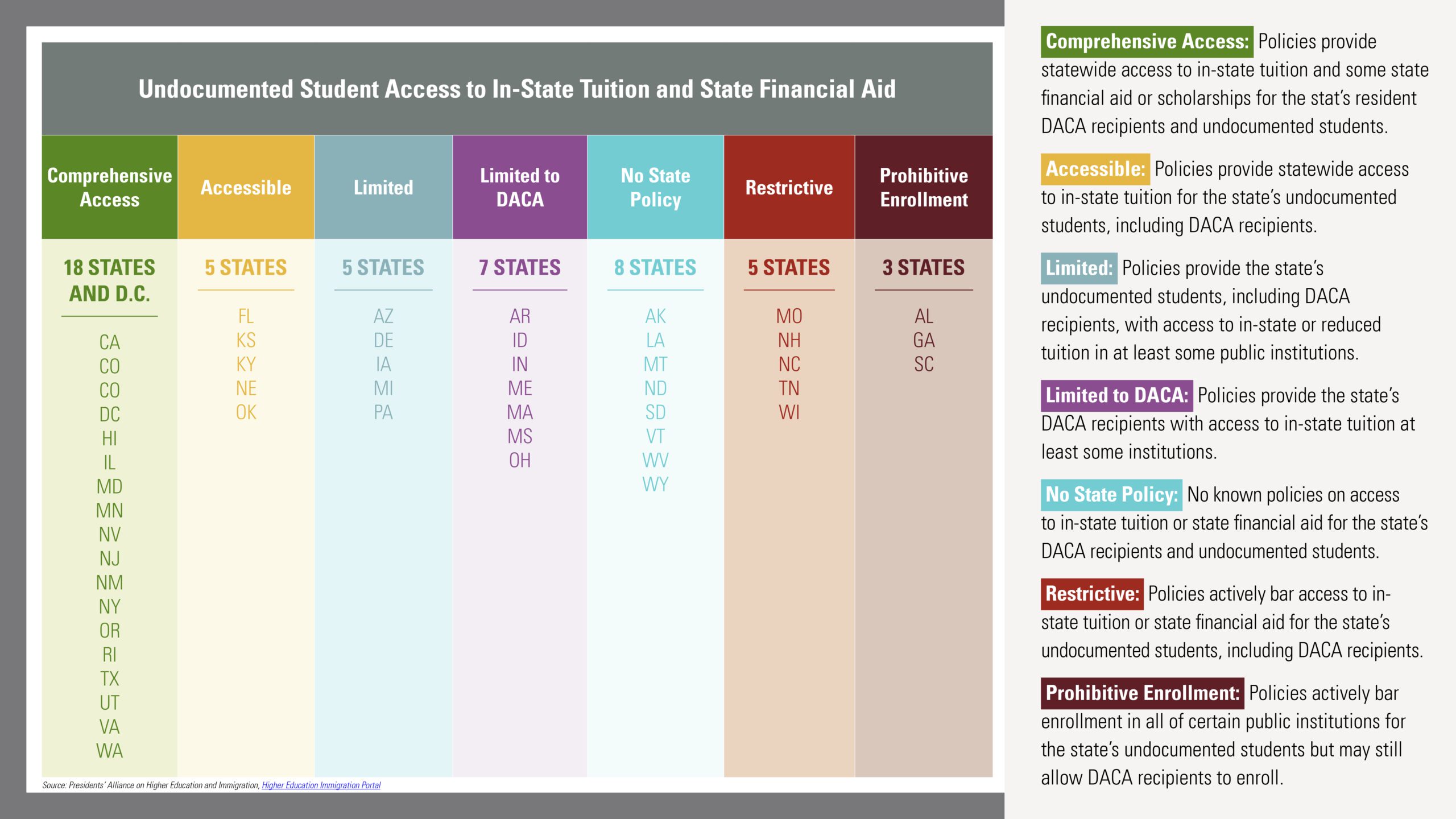

Yet states often have their own restrictions on enrollment access, in-state tuition, and state financial aid for undocumented students. The result is a patchwork of different policies in different states. Federal law bars the provision of “state and local public benefits,” including “postsecondary benefits,” for undocumented students unless a state passes a law making them explicitly eligible. The Presidents’ Alliance for Higher Education and Immigration — a nonprofit, nonpartisan alliance of college and university leaders dedicated to helping the public understand how immigration policies impact students — has been tracking where states are on higher education equity and access, degree completion, and career prospects for DACA and undocumented students via its Higher Education Immigration Portal. It provided essential data for a new report by researchers at The Education Trust, “Higher Education Access and Success for Undocumented Students Start with 9 Key Criteria.” The picture the data paints is mixed. Seventeen states and D.C. allow undocumented students to qualify for in-state tuition and state financial aid. Arizona, which just passed Proposition 308, will bring that number to 18, once the policy is officially implemented. State financial aid for students is typically in the form of scholarships, grants, or loans. Five U.S. states (FL, KS, KY, NE, OK) allow access to in-state tuition, but do not provide access to state financial aid for undocumented students.

The remaining 27 U.S. states offer a mishmash of policies around enrollment access, in-state tuition, and state financial aid for undocumented students (see table below). Four states provide in-state tuition at some but not all institutions; seven states provide in-state tuition to students only if they are DACA recipients and sometimes only at certain institutions; eight states have no known or established policies extending in-state tuition and state financial aid to undocumented students; five states actively block access to in-state tuition; and three states actively block access to in-state tuition and, in at least some cases, enrollment for undocumented students.

Providing full tuition equity for undocumented students means providing them with enrollment access at state institutions of higher education, in-state tuition, and state financial aid. Without access to full tuition equity, many undocumented students will struggle to pay for college and be left to navigate a complicated web of policies to access and complete college or be locked out of college entirely. Flora, an undergraduate student without DACA from the University of California, Los Angeles, notes that even if states do not block access to in-state tuition for undocumented students, “[p]icking and choosing ways to support undocumented students without full access to tuition equity is limiting. It is states opening the door to undocumented students, but not all the way. States should allow full access to in-state tuition and state financial aid [for undocumented students].”

Esder, a DACA recipient and college graduate from New Jersey, which provides access to in-state tuition and state financial aid for undocumented students, echoes that concern: “Without access to in-state tuition and state financial aid, undocumented students face barriers to higher education, not because of their qualifications, but because they are not eligible for an affordable education.”

Research shows that offering in-state tuition and state financial aid to undocumented students is a net positive, because it increases college enrollment and improves outcomes such as academic achievement, credits attempted, and first-semester retention. And that’s not counting the other benefits, including economic and social impacts. Esder explains what having higher education access and tuition equity means to her. “[It] is a concrete policy that in a big way translates to campus belonging,” she notes. “It is the state you grew up in validating and affirming your belonging, both as a resident of the state and also in your campus community.”

Colleges and universities can further expand college access for undocumented students by ensuring that on-campus fellowship and internship opportunities are open to undocumented students, and that they are paid. Providing paid opportunities for undocumented students to help them offset the many costs of college attendance beyond tuition is important. Higher education institutions can provide stipends to students who accept off-campus internships, as long as the fellowship or internship focuses on training, incorporates a learning component, and doesn’t constitute an employment relationship. Such opportunities may not only make college more affordable for undocumented students but help them “gain valuable career exploring experiences,” notes Flora.

In some states, like California, innovative programs provide funding opportunities for undocumented students while giving them educational training or community service experiences that allow them to explore potential careers. The California College Corps, for example, gives fellows $10,000 in exchange for serving in community-based organizations or fields such as education, and the California Service Incentive Grant encourages California Dream Act applicants to perform community or volunteer service in exchange for a grant of up to $4,500. More efforts might be on the way. Opportunity for All, a UCLA-based initiative, which provides paid internships, apprenticeships, and pathways to employment for young people, argues that a 1986 federal immigration law that prevents employers from hiring undocumented individuals does not apply to states. Their analysis, which could face legal challenges if implemented, suggests that undocumented individuals could be hired for state jobs, including at public colleges and universities, such as the University of California, California State University, and California Community College campuses.

Some recent efforts to expand higher education access for undocumented students through in-state tuition, state financial aid, and paid experiential learning opportunities have resulted in significant wins. Yet, these policies are not enough, especially when they apply only to undocumented students with DACA — who make up less than half of the undocumented student population in higher education — and given the precarity of DACA, as Flora rightly notes: “[T]oday, most undocumented students in college no longer have DACA,” she adds.

State and institutional-level policies can help some undocumented students access higher education, but without congressional action providing a pathway to citizenship for undocumented students, access to a college education will remain out of reach for many undocumented students. Many of these students grew up in the U.S. and all of them deserve the same access to a higher education as their counterparts. It is the responsibility of Congress to pass a permanent, legislative solution once and for all. “Only a permanent solution will open all the doors at the end of the day,” Flora says.