Pursuing a higher education is unaffordable for many low-income students in the U.S., and the struggle to pay for college is intensified for many student parents, who often must pay for high-quality child care, on top of tuition, books, and basic needs, such as food and housing which together comprise what we call the student parent net price. To make matters worse, most student parents are unable to access child care subsidies that might help mitigate the financial burden of paying for child care.

In this follow-up blog to our report on student parent affordability, we examine how barriers of access to child care subsidies are exacerbating the financial pressures on student parents, many of whom juggle work and parenting responsibilities and live paycheck to paycheck while pursuing a higher education, sometimes at the expense of their own physical and mental well-being.

Child care is expensive. The estimated annual cost of child care in the U.S. exceeds $10,000, according to CNBC and the First Five Years Fund, an organization that works to sustain and expand the support for early learning at the federal level, while identifying and advancing new and innovative ways to increase access to high-quality early childhood education for children from low-income families. That cost has continued to climb amid the pandemic and thanks to a nationwide shortage of child care providers and inflation. Dual-income households now spend 15% or more of their pay, on average, on child care, while single-income households spend roughly 36%, on average, the same report notes.

The high price of child care makes the out-of-pocket cost of attending a public college 2 to 5 times higher for student parents than it is for their peers. For those with more than one child, the financial strain is even greater. That’s prohibitive for many student parents, who comprise more than one-fifth of all college students and are pursuing a higher education so they can build a better life for themselves and their children. These student parents are disproportionately single, people of color, from low-income backgrounds, and were already struggling to find and pay for high-quality child care before the pandemic reduced the availability of child care and drove costs up further.

Without affordable child care, many of them will have a hard time staying in school.

Sadly, the facts already bear that out: Student parents are far less likely to finish a college degree than their counterparts without children. A recent report by researchers at The Education Trust — “For Student Parents, The Biggest Hurdles to a Higher Education Are Costs and Finding Child Care” — shows that the lack of affordable child care is a major reason why. According to that report, there is no state in which a student parent can work 10 hours per week at the minimum wage and afford both tuition and child care at a public college or university. In fact, a student parent in a minimum-wage job would need to work 54 hours a week, on average, for 50 weeks just to cover the costs of tuition and center-based child care.

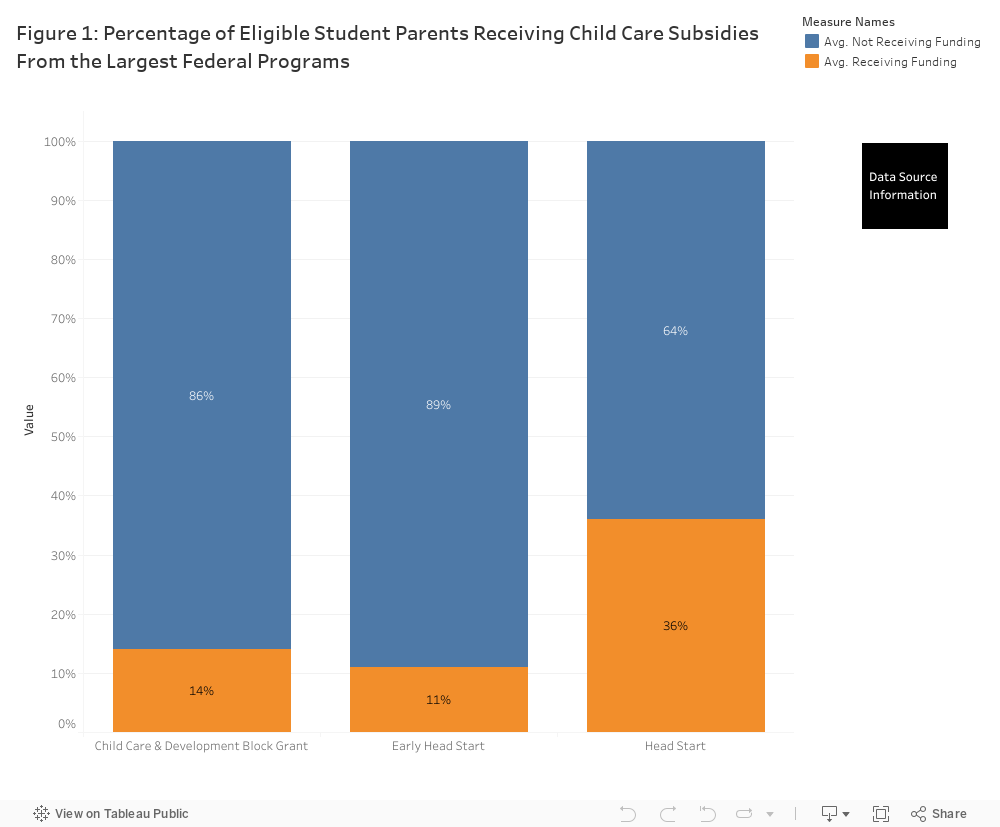

Expanding access to child care subsidies would help ease that financial burden and reduce the student parent affordability gap — which is the average amount that a student parent from a low-income background must pay annually to pursue a degree at a two- or four-year public college and cover the costs of child care, after grants, scholarships, and earnings from working 10 hours per week at the state minimum wage have been applied. It might also reduce the number of hours student parents must work to cover child care expenses and leave them more time for their academic studies — both of which would make them more likely to graduate.

Giving student parents access to high-quality child care at little or no cost would also be a boon for their children — in more ways than one. Research shows that having a safe and nurturing environment is essential to a child’s development. What’s more, students and student parents who obtain a bachelor’s degree have higher earnings and are more likely than those with only a high school diploma to achieve financial stability, which, in turn, is linked to higher educational attainment and more positive outcomes for their kids, according to a Georgia Budget & Policy Institute paper.

Sadly, the U.S. spends less than 0.5% of its gross domestic product (GDP) on early care and education — far less than many other countries — and the supply of child care providers and federally funded child care programs in the U.S. doesn’t come anywhere close to meeting the demand for high-quality child care.

Addressing these insufficiencies is vital. Fortunately, there are key things that federal, state, and higher education leaders and policymakers can do to help.