More Asian American Representation: Because Children are Naturally Inquisitive

Politically repressive campaigns such as anti-CRT are harmful to children’s cognitive and civic development.

In 2018, my then three-year-old daughter Té Té asked me, “Mama, are we Black?”

“No, we’re not Black,” I answered.

“Are we white?” she asked.

“No, we’re not white,” I said, suspecting what she would ask next.

“Then what are we?” she wondered out loud.

“We’re Asian American,” I responded. “Can you say, ‘Asian American’?”

“Asian kAH-merican,” she slowly pronounced in her sweet toddler voice. She precociously pushed back, “But Asian kAH-merican isn’t a color!”

Té Té wasn’t wrong. Asian Americans are all different colors. Asian American is a racial category and wide umbrella term that includes South Asian Americans (e.g., Bengali, Indian, Pakistani), Southeast Asian Americans (e.g., Cambodian, Filipino, Hmong, Lao, Vietnamese), and East Asian Americans (e.g., Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Taiwanese). As I explain to my daughter in my new book, Asian American is Not a Color: Conversations on Race, Affirmative Action, and Family (Beacon Press, 2024), Asian American is a political identity rooted in a solidarity ethic that young people created during the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s for collective cross-ethnic community-care and power building.

My daughter’s observation stunned me — a race scholar and education policy researcher. When I became a mother, I expected there would be mother-daughter conversations like this, but I had not anticipated them to come so early in her life. I remember fumbling through some sociological explanation about how race is a social construction. I was out of my depth when it came to supporting her curiosities about the world.

Thankfully, Té Té’s teachers have been generous partners in supporting her inquisitiveness and learning. I may be a professional race scholar, but they are the experts when it comes to early childhood and elementary education. We do not live in a state that has vilified, or even banned, teaching about race, gender, and sexuality.

Then, when Té Té was in the second grade, she came home and asked me, “Are we colonizers?” When I asked her why she was asking, she said, “We’re learning about the colonization of Haiti and the Haitian Revolution at school. America colonized Haiti a hundred years ago. You say we’re American, so doesn’t that make us colonizers?” I confess these questions made me uncomfortable.

As I explain in my book, this conversation made me wonder if fellow parents who want to stop teachers from teaching about race, gender, and sexuality had similarly uncomfortable conversations. But instead of seeing their children’s questions as emblematic of good teaching that encourages inquisitiveness, they have invested in a political project to shut down discussion, learning, and education.

These politically repressive campaigns are harmful to children’s cognitive and civic development. They also stoke divisions in our communities, allowing the powerful political elite to harm communities of color for economic profit.

When Té Té asked if we were colonizers, it led to a rich mother-daughter conversation. We talked about our family’s history. My parents grew up in Hong Kong, which was a British colony until 1997. They immigrated to the U.S., holding British Dependent Territories Citizen passports. They were colonial subjects under Queen Elizabeth II and immigrant settlers on Native American lands–namely, the homelands of the Massachusett and Pawtucket peoples–where I was born and raised.

Children are naturally inquisitive. They have a right to an equitable education that honestly affirms the complexities of our histories, the diversity of social realities, and encourages the development of critical thinking skills for problem solving and civic possibilities for a robust and diverse democracy.

A culturally affirming education for the 21st century does not flinch from difficult conversations about complex issues.

Unfortunately, some political actors want to repress children’s natural desires and rights to learn and understand their relationships to the complex world around them. Some seek to erase our histories through book bans and censorship of curriculum. As of May 2024, twenty states have laws restricting how teachers can discuss race, gender, gender identity, and sexual orientation. The Legal Defense Fund (LDF) states, “These attacks are part of a larger effort to suppress the voice, history, and political participation of Black Americans,” and other people of color.

Most people (more than 75%) want schools to teach about our complex historical truths. This includes 7 in 10 Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders who support “teaching historical topics such as slavery, racism, and segregation” and the history of AAPI communities. The majority of Americans understand that learning our histories is essential for our diverse democracy to grow.

Starting in 2020, as public attention turned toward a documented rise of anti-Asian racism, a policy window opened to advance Asian American Studies in public schools. Starting with Illinois, several states began requiring the inclusion of Asian American history in public K-12 classrooms.

This is progress. The first time I had a chance to learn about Asian American histories — how people from Asian diasporas confront racism, strategize to overcome discrimination, and contribute toward U.S. society — was in college. The Asian American Studies class I took gave me a language to understand painful experiences with intersectional racism in my life. I learned how such a vastly diverse population made up of dozens of ethnic groups of people who speak dozens of distinct languages, that practice an array of religious and spiritual traditions, and arrived in the U.S. under disparate conditions and histories of global empire, labor exploitation, and war, came to be identified as Asian American. I learned how Asian Americans experienced the widest income disparities, with Asian Americans at both the highest and lowest economic strata.

Asian American Studies and Ethnic Studies classes and learning communities developed my critical thinking and problem-solving skills in a way that improved my overall academic performance and college experience. They improved my understanding of my family’s history and opened possibilities for intergenerational healing. I also learned how Asian American experiences were connected to other communities of color and how Asian Americans have been part of movements for social justice. I was inspired to be part of efforts to make the world more humanizing and just.

I am not alone in these experiences. Researchers have found that Ethnic Studies curriculum improves academic outcomes for students of color, self-perceptions, and cross-cultural appreciation and interactions necessary for a diverse democracy. So,it is an exciting time to witness the growth of Asian American Studies in public schools. But it is also disheartening to witness attacks on African American History in schools. As the Association for Asian American Studies explained, “There can be no truly representative or accurate teaching of Asian American and Pacific Islander history without African American history. Doing so would only offer a diluted picture of historical reality.”

To be sure, it can be uncomfortable and unsettling to learn about and reflect on U.S. history and its contemporary implications through multiple perspectives that do not provide a singular righteous (white) American story of triumph.

Our histories are not simple. Our future as a democratic society depends on our capacity to teach and learn with honesty about our historical conflicts, political struggles, and accomplishments. As LDF explains, “We cannot progress further and build a better society for our children if we can’t talk about where we are coming from. Defending education that is historically accurate and inclusive of the experiences of Black Americans, Native Americans, Latinx Americans, Asian Americans, women, and other marginalized groups is the work we must all now do in the face of this coordinated backlash against an inclusive America.”

OiYan Poon is co-director of the College Admissions Futures Co-Laborative, the NAACP LDF Thurgood Marshall Institute senior research fellow for education equity, and author of Asian American is Not a Color.

Each piece in this series is accompanied by relevant resources and book recommendations provided by one or more of our partners, with input from the authors.

OiYan Poon recommends Teaching Asian America in Elementary Classrooms, Asian American Racialization and the Politics of U.S. Education, The Racialized Experiences of Asian American Teachers in the US, and the Asian American and Pacific Islander Multimedia Textbook as resources for learning about Asian American representation in U.S. education.

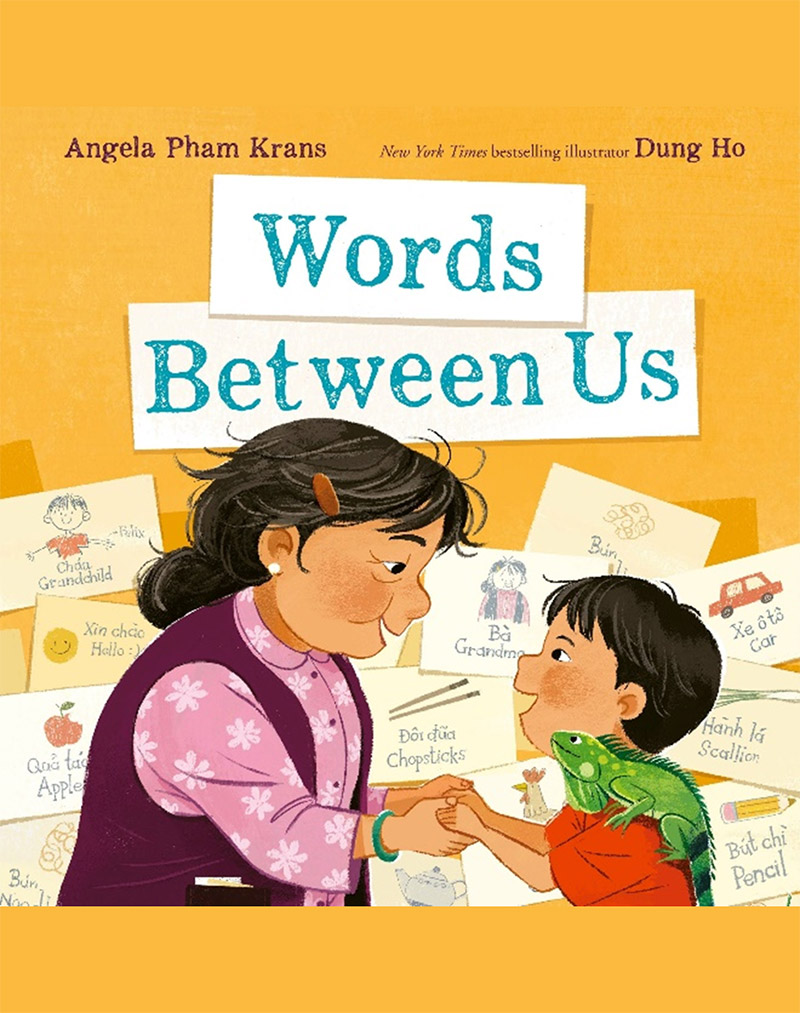

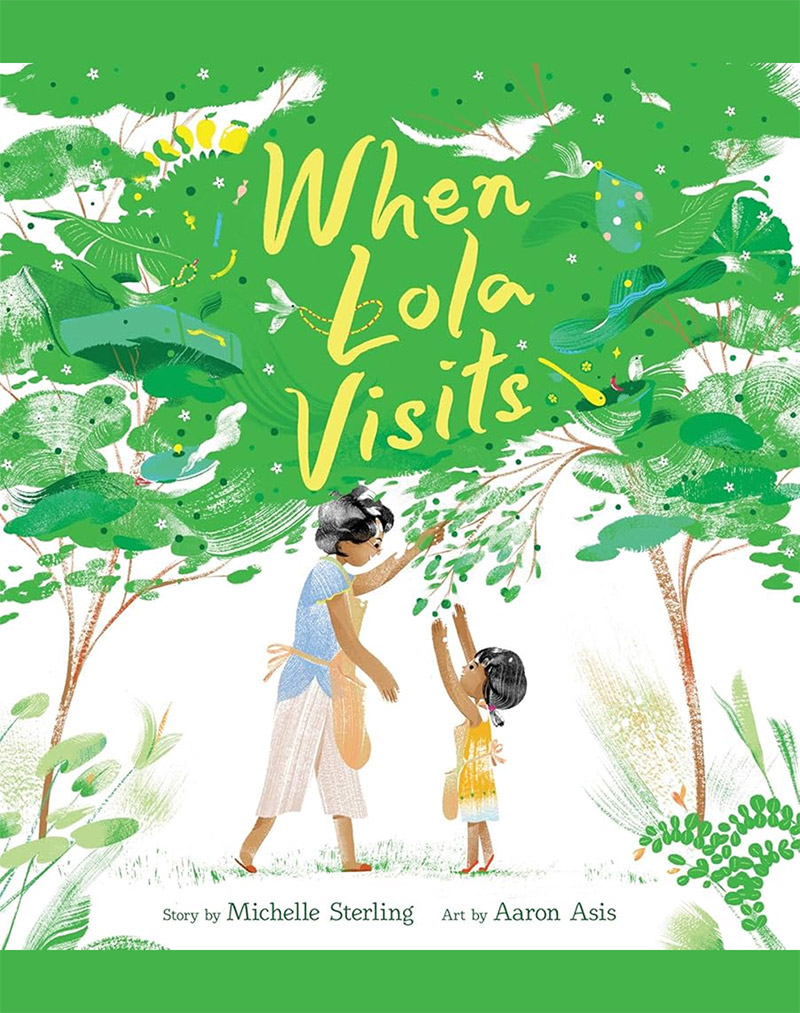

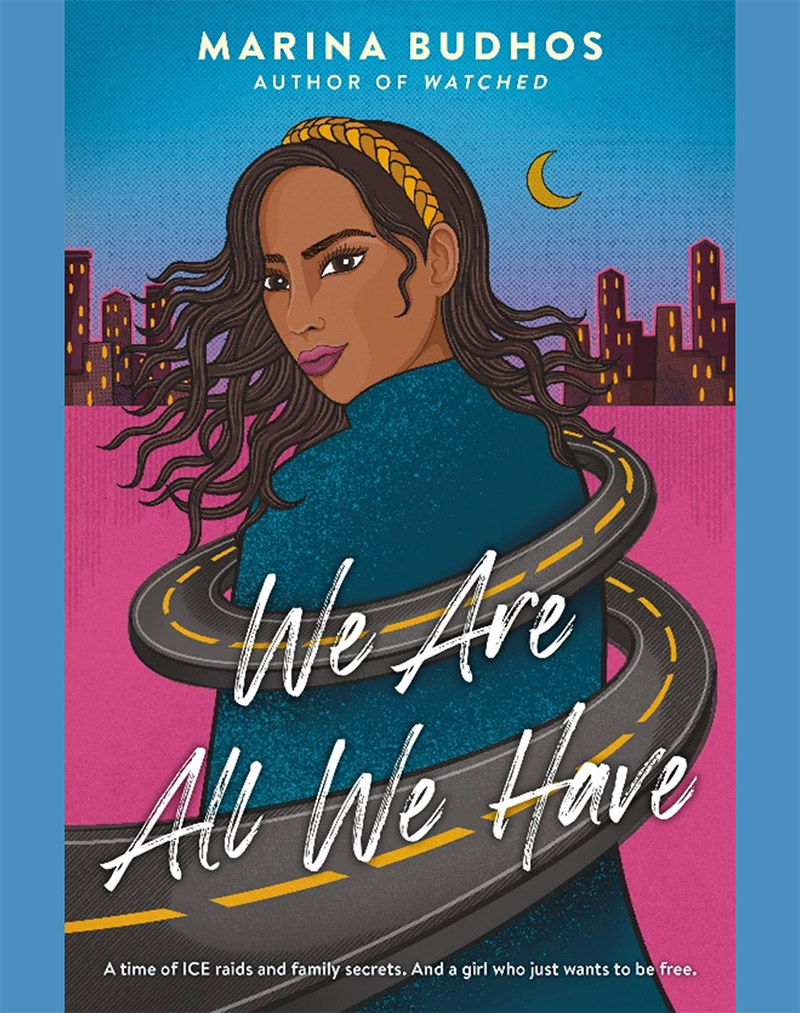

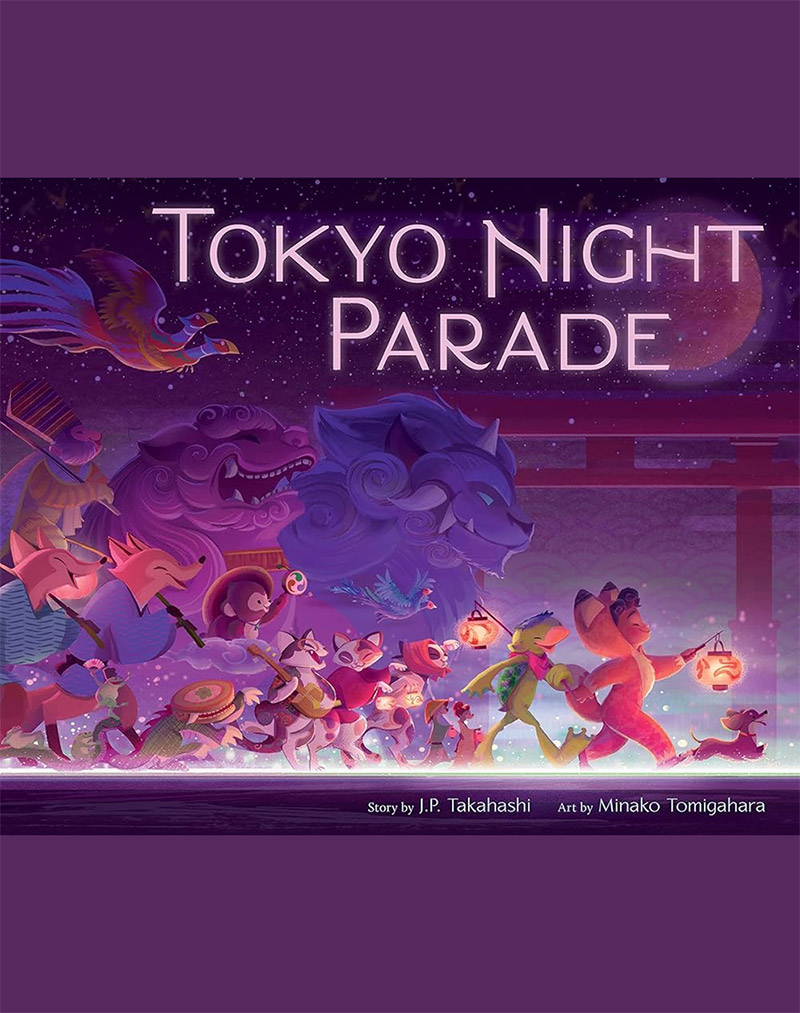

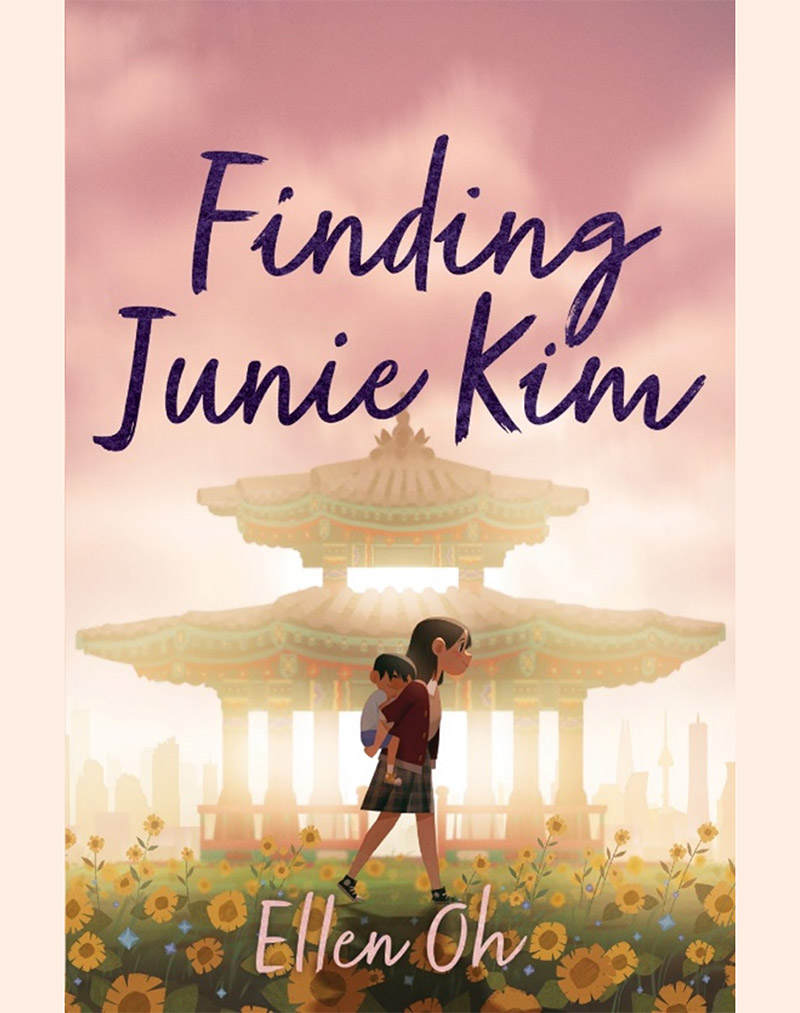

The Education Advocacy team at Asian Americans Advancing Justice | AAJC offers capacity building resources for local and state-level organizations to advocate for inclusive K-12 curricula (including Asian American Studies) and equitable access to educational opportunities. Together with our education advocacy community partners AAVEd and AAPI New Jersey, we recommend the following titles for K-8 readers.