The Mores of Muslim Representation in Children’s Books

There are almost 2 billion Muslims around the world, but represent only 1% of the youth literature published.

It took almost four decades for me to see my life experience represented in a book.

In April 2018, I was a 38-year-old married mother of three when I first saw myself and my family affirmed in a book. Mommy’s Khimar is a children’s book that playfully explores a young Black Muslim girl’s fascination with her mother’s headscarves and tells the story of her family and community’s support of her as a person, including the support and love of her Christian grandmother. The moment of discovery and reflection brought tears to my eyes — I didn’t realize that it had been missing until I found it. Growing up at a time when Sweet Valley High and The Hardy Boys were most popular, I never considered a world where an African American Muslim family would be included in a book that I could grab off a library or bookstore shelf and take home with me.

There are almost 2 billion Muslims around the world, but according to the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, only 1% of the youth literature books reviewed annually by the center, published in the U.S. in a given year, depict Muslim representation of any kind.

A 2014 Pew Research Center study found that the majority of people in the United States say they do not know a Muslim. For many, what they know about Muslims comes from the distorted windows of media misrepresentation.

Recent studies and reports by the University of Southern California’s Annenberg Inclusion Initiative and the Media Portrayals of Minorities Project (MPoMP) at Middlebury College have laid bare the truth that the dominant narratives and portrayals of Muslims in the U.S. Media are negative and that Muslims are the most negatively portrayed American group of color in this country, directly leading to Islamophobia and violence faced by Muslim individuals and communities.

These portrayals have profound repercussions on the well-being of Muslims. According to a 2020 study by the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU), half of Muslim families surveyed reported incidents of bullying targeting their children’s faith, with a third attributing the bullying to teachers or school officials.

Common Sense Media’s Inclusion Imperative: Why Media Representation Matters for Kids’ Ethnic-Racial Development report examines the role of media representation in the ethnic-racial development of children in both understanding themselves and others. Their findings on Middle Eastern, Arab, and Muslim Representation in Screen Media, indicate that higher quality depictions of Muslims lead to decreased support from white audiences for policies that negatively impact Muslim Americans and their families, and for Muslim American audiences, lead to increased perceptions of safety and belonging.

I should not have had to wait almost four decades to see the richness and power of my heritage as an African American Muslim, my reality of worshipping in a multiethnic religious community, and my loving extended, interfaith family included in a book, nor should any other child. Fortunately, change has come.

As a Muslim Indonesian Okinawan American, I have not expected that my exact experience would be depicted on the pages of children’s books, yet my feelings for books that depict Islam and Muslim American experiences that capture parts of my identity but not others, are bittersweet.

Indonesians are the fourth largest population in the world, and the most populous Muslim country— over 80% of its population is Muslim, which represents 13 % of the global Muslim population. In the U.S., Pew estimates that as of 2019 there are about 129,000 Indonesian Americans, the 15th largest group of Asian Americans and one that is fast growing. This population is diverse, reflecting many ethnicities and religions, with a minority Muslim population of about 25%.

There are few examples of Indonesian/Indonesian American representation in children’s books, let alone Indonesian American Muslims. But looking at global representation it is still surprising to see little representation in children’s literature in U.S. publishing or of translated books. If Indonesia or Indonesians are depicted in a storyline, it is only an incidental mention, without detailed religious or cultural practice. Until just this month, the closest reflection of my identity that I have seen is Mommy Sayang by Rosana Sullivan, a book about a little girl and her mother living in a small Malaysian village.

Aisha’s Colors by Nabila Adani, a book about a family vacation, set in Jakarta and the Javanese countryside, and published by Candlewick was just published in September of this year.

The esteemed educator, Rudine Sims Bishop, often referred to as the “mother of multicultural literature,” whose literary framework references books as mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors, wrote: “When lighting conditions are just right, however, a window can also be a mirror. Literature transforms human experience and reflects it back to us, and in that reflection, we can see our own lives and experiences as part of a larger human experience.”

We established Hijabi Librarians in 2018, after many years of working to find Muslim colleagues in youth librarianship and discussing Muslim representation in the field and literature. Our early conversations as a collective of Muslim librarians inevitably turned to our experiences with books. When had any of us ever seen ourselves, our families, and our communities represented in literature?

Our answers were the same: We had not. For us, the work is personal.

Since launching the Hijabi Librarians collective in 2018, our work has been focused on:

Our toolkit is applicable, and useful, for anyone striving to thoughtfully select works of literature that engage the full spectrum of the Muslim experience — especially educators.

To quote Professor Muhammad again, “Not only is it important to teach youths who they are, but educators should also teach students about the identities and cultures of others different from them. When we have true, clear, and complete understandings about people different from us, we are less inclined to hate, show bias, or hold false views of others.”

Understanding Muslims — as multi-faceted human beings and as members of complex, diverse communities — combats reductive representation which often conflates and flattens the experiences of Islam and Muslims and other religious groups, such as Sikhs, whose religious practices are religiously conflated with Muslims, or discussions of the political landscape in Southwest Asia and North Africa that erase the area’s rich Christian history and that of other religious communities.

Ultimately, the stories about Muslims that have been and continue to be published are important and add to the canon of children’s literature but cannot capture all the stories of children in any one classroom.

Holidays are just one opportunity for teachers, students, and families to bring narratives of Muslims into schools and communities. We hope that as more children’s books with Muslim subjects are published the nuances of multilayered identity will be further explored.

We will continue to work toward advocating for inclusion of Muslims from stories, authors, and publishers in children’s and young adult books that showcase the full humanity of Muslim youth in all media with faith, love, and pride — because better Muslim representation and understanding are connected to the liberation of all.

Ariana Hussain, MLIS and Mahasin Abuwi Aleem, MLIS are co-founders of Hijabi Librarians and authors of the Evaluating Muslims in KidLit Toolkit.

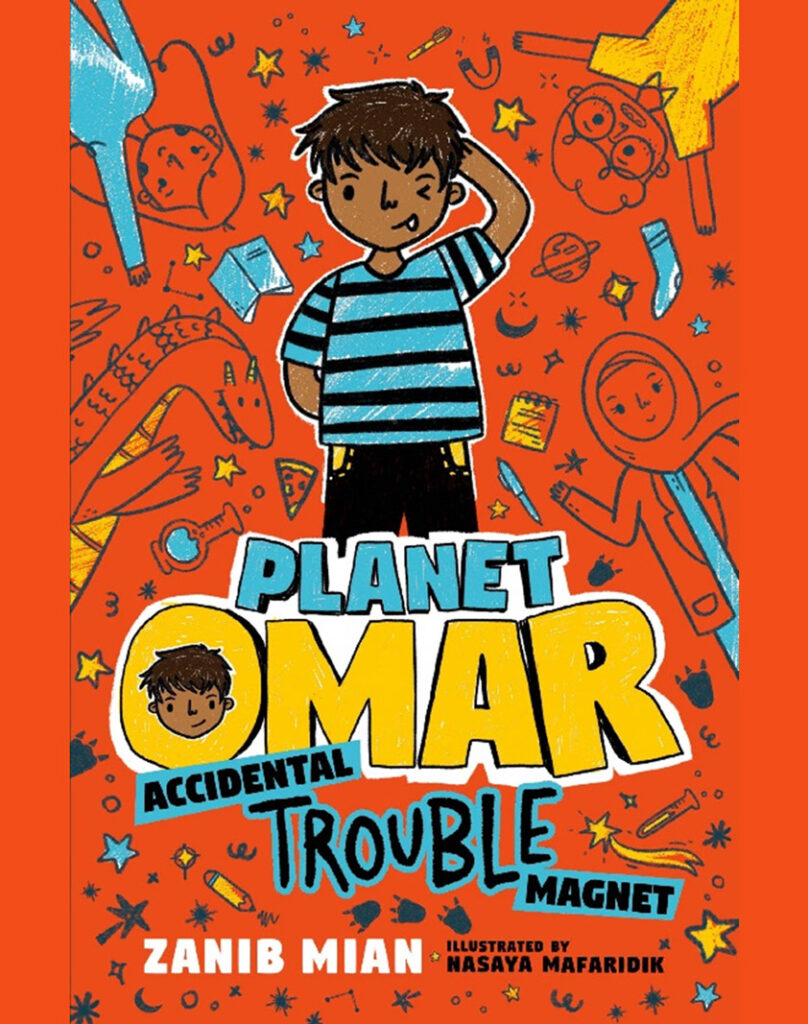

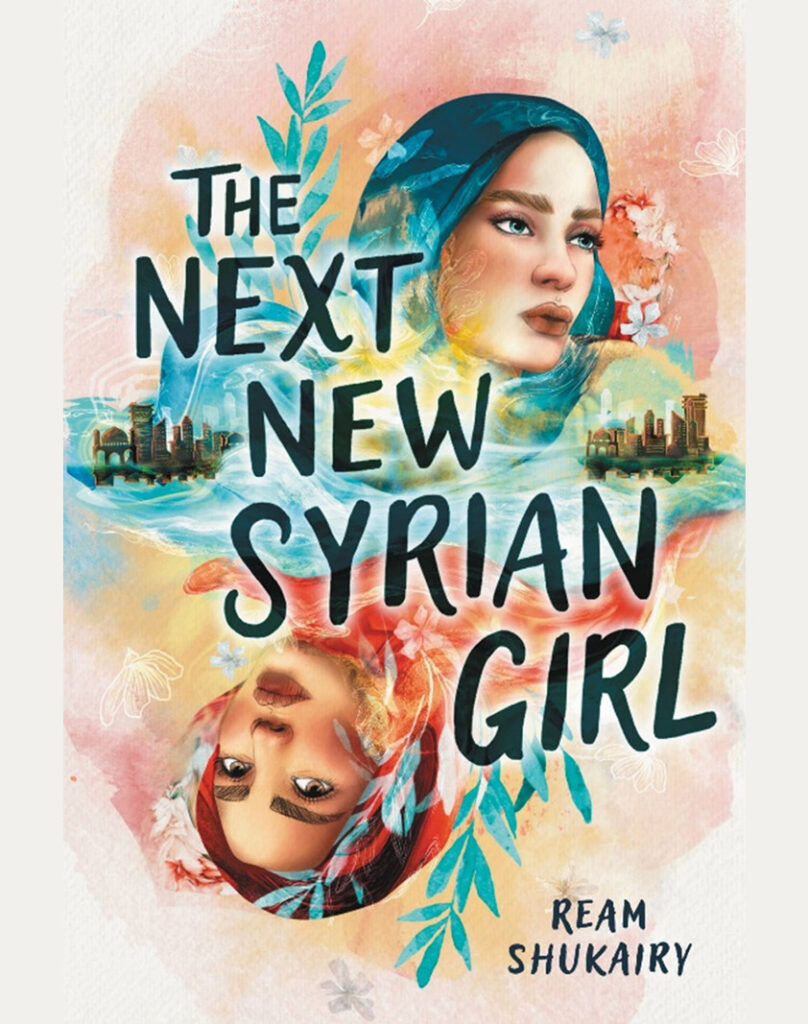

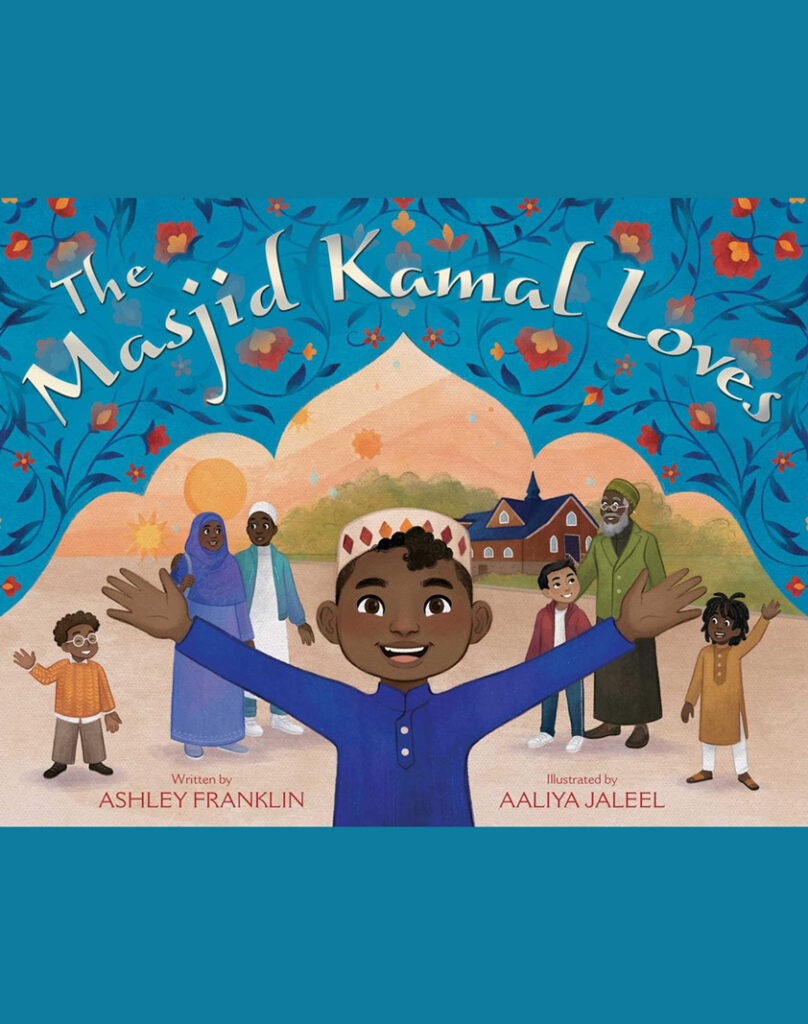

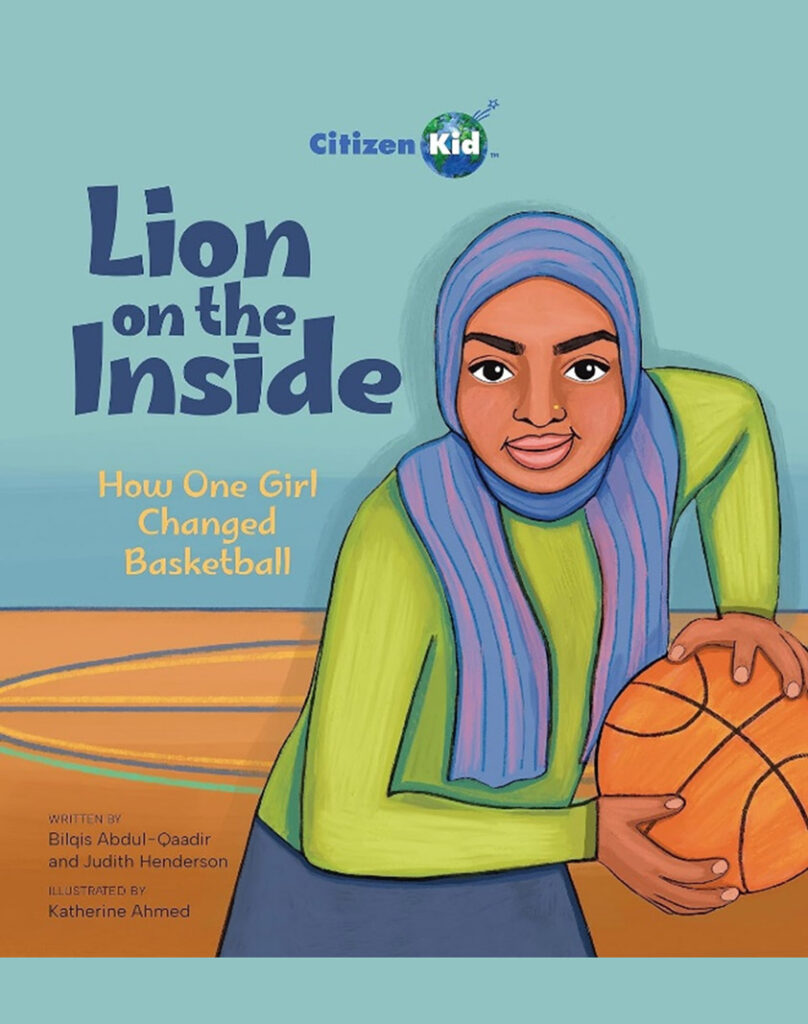

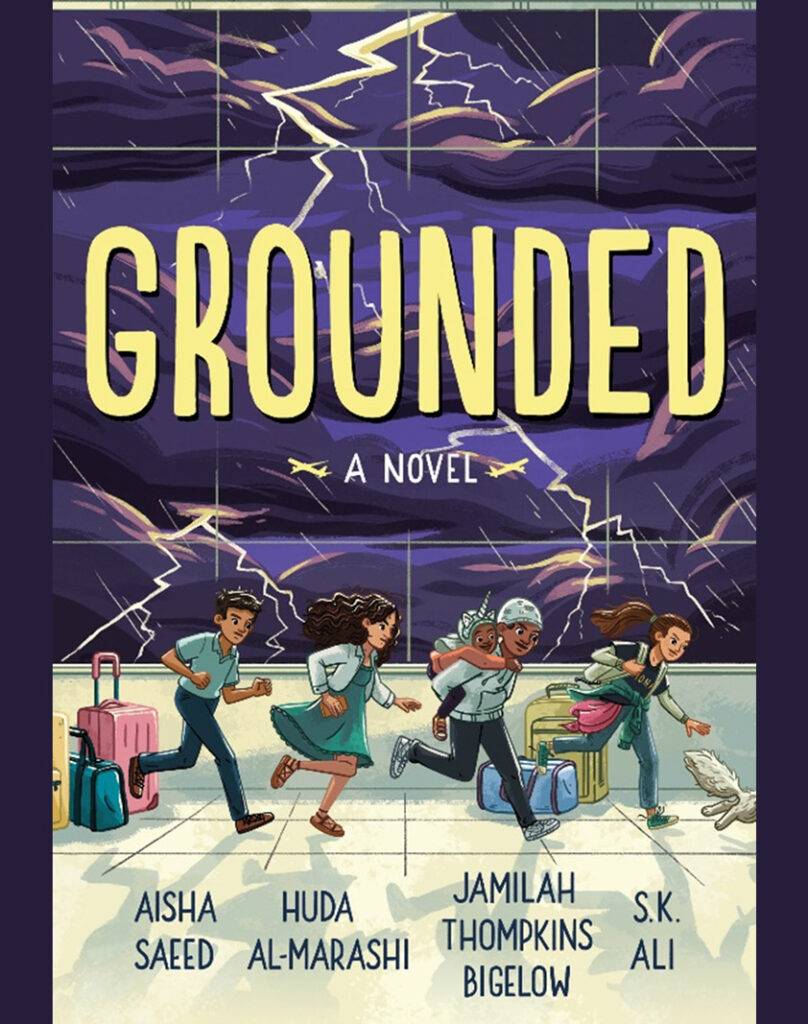

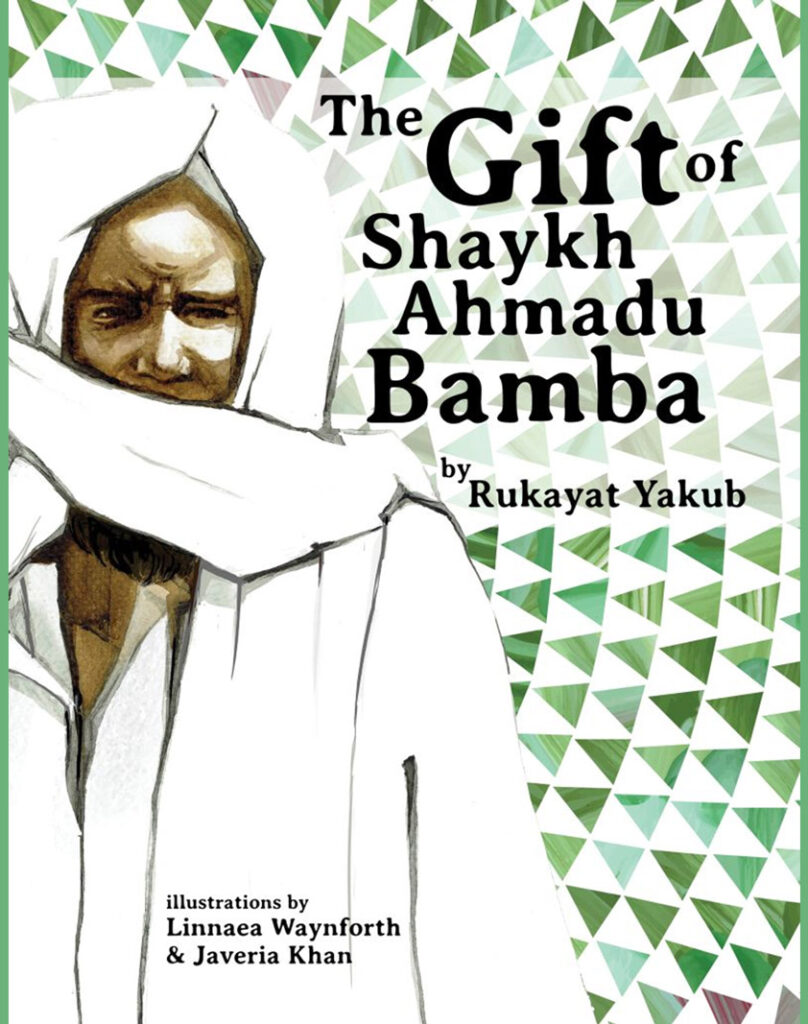

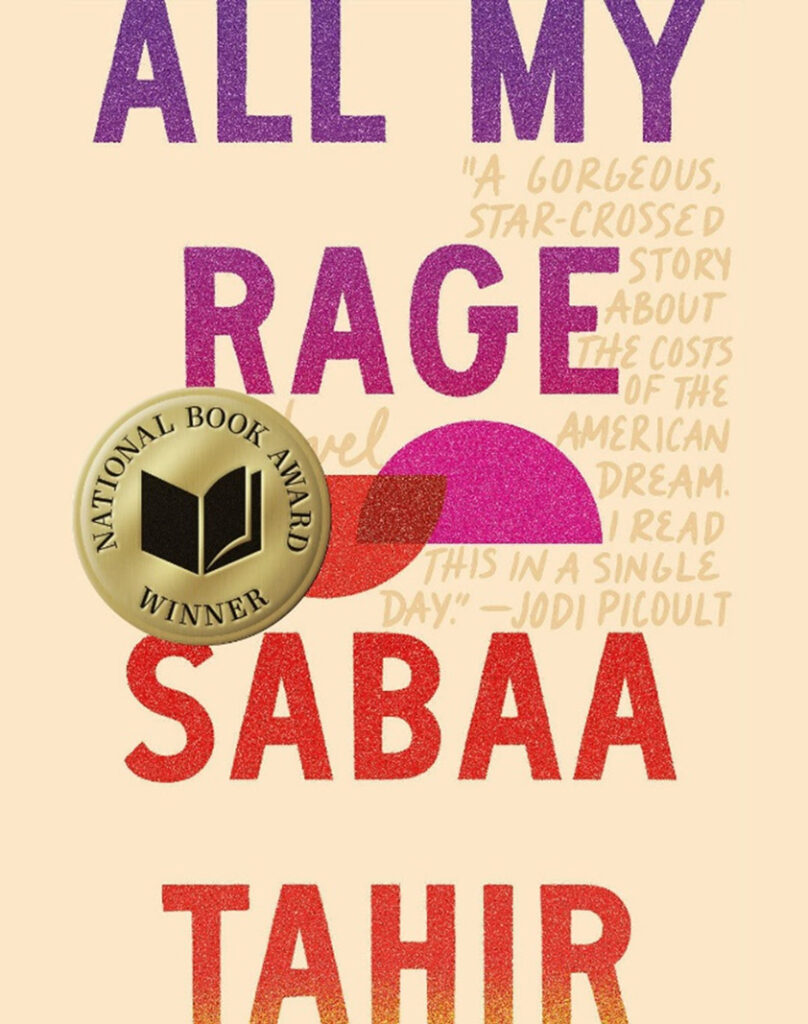

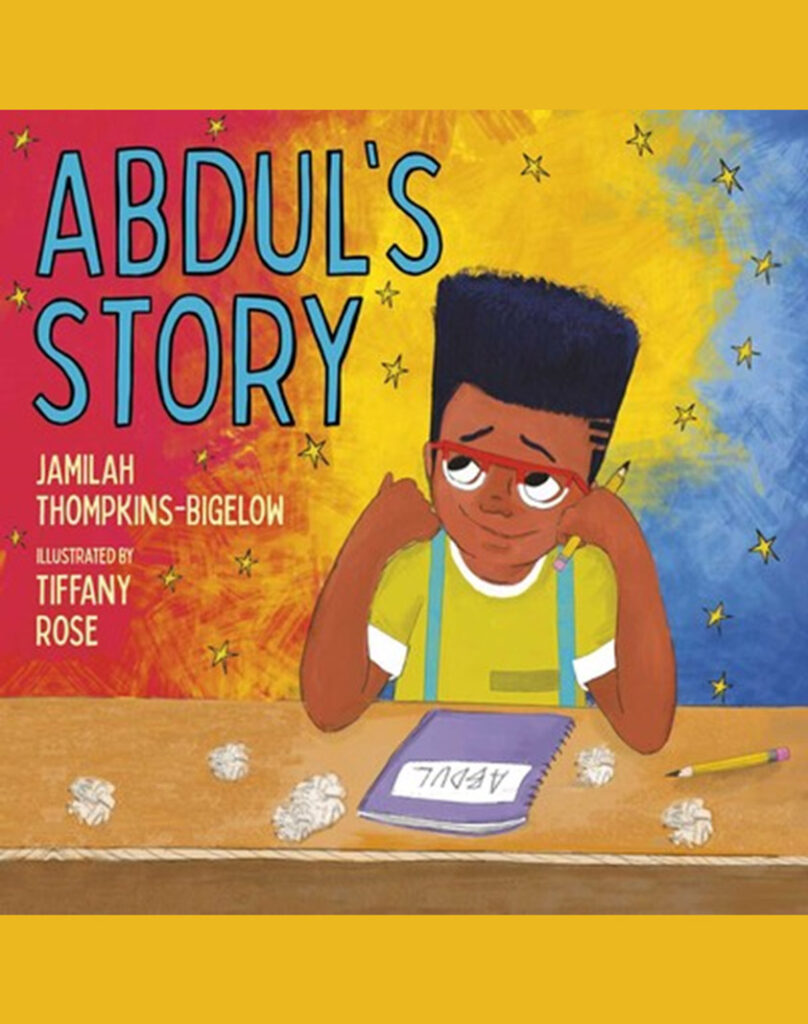

Each post in this series is accompanied by relevant resources and book recommendations provided by one of our partners, with input from the authors.

Dr. Jamillah Karim is an award-winning author, speaker, blogger, former Professor of Religion at Spelman College, and consultant for the Islamic Networks Group (ING). ING is a nonprofit organization educating for cultural literacy and mutual respect with affiliates and partners around the country that are pursuing peace and countering all forms of bigotry through education and interfaith engagement in schools and different organizations. Educators and organizations can connect to guest speakers as well as use ING’s online curriculum guides on a variety of topics related to cultural awareness and building bridges.