This year has been like no other in the history of the United States. More than 550,000 people (and counting) have died of COVID-19 in the U.S. That is more than the number of Americans killed in World Wars I and II combined. But the pandemic’s devastation has not been distributed equally. Communities of color have disproportionately borne the brunt of it. One in 1,000 Black Americans has died of COVID-19. And while the relative share of deaths among White people has increased in recent months, people of color have died at much higher rates over the last year. Communities of color have also been hardest hit by job and income losses amid the outbreak. That’s due, in no small part, to the historical legacy of slavery and racism on which America was built, and the uncomfortable truth — laid bare by the pandemic — that while slavery in the U.S. is no more, structural racism and racial disparities still run deep: They are longstanding, pervasive, systemic and intentional. And COVID-19 is exacerbating many of these already glaring disparities.

Nowhere is this more evident than in education. Americans have long touted education as the great equalizer, but the data clearly show that Black students consistently get the short end of the stick. Black families have less access to high-quality pre-K, while Black students attend schools that are underfunded. They also have less access to experienced teachers, a full range of math and science courses, school counselors and gifted/talented, advanced placement, and international baccalaureate programs. Black students get the illusion of education without the critical components of a quality education. This systemic approach to denying Black students a quality education has resulted in inequities in high school graduation, college enrollment, graduation rates and degree attainment. In fact, educational attainment for Black adults in this country today is the same rate it was for White adults in 1990. There are also vast disparities by gender. Black women are roughly 10 percentage points more likely than Black men to hold a college degree.

What’s more, Black undergraduate enrollment has fallen in recent years. The Education Trust’s report, “Segregation Forever”? The Continued Underrepresentation of Black and Latino Undergraduates at the Nation’s 101 Most Selective Public Colleges and Universities, noted that most public flagships enroll a smaller percentage of Black students today than they did 20 years ago. And the pandemic isn’t helping matters. According to the National Student Clearinghouse, Black student enrollment in higher education was down 7.5 percentage points last fall. And while overall enrollment at public four-year colleges declined by only 4 percentage points last fall, enrollment at community colleges — which serve a disproportionate share of students of color — dropped precipitously, by 13 percentage points.

Those losses should ring alarm bells; so should the steep decline in first-time enrollment among Black students, which sank nearly 19 percentage points across all sectors. Enrollment of undergraduate Black men at community colleges was particularly hard hit, falling 19.2 percentage points, compared to a decline of 9.0 percentage points for Black women. No matter how we slice the data, it is clear that the educational systems in our country, from pre-K through postsecondary, are failing Black students. None of this bodes well for our country’s economic future, given that youths of color represent one of the fastest-growing segments of the U.S. population and now comprise a majority of undergraduates at public colleges. No doubt it’s why so many states have set ambitious attainment goals.

It’s time for legislators, institutional leaders, and K-12 administrators to get serious about targeting resources, closing gaps, and improving opportunities for Black residents.

To find effective remedies, we must first explore and understand national and state trends. In this brief, we examine postsecondary degree attainment for Black women and Black men. We continue to see differences in attainment between Black and White women and men. Additionally, we find differences in attainment between Black women and men.

Educational Attainment Among Black Women and Men in the United States

Our previous work identified a 17 percentage point gap in educational attainment between Black (30.7%) and White adults (47.1%). This disparity persists when we examine educational attainment by gender. Slightly more than half of White women (51.4%) have a college degree, compared to 36.1% of Black women. That’s a 15 percentage point gap. The gap is even wider among men: 44.3% of White men have a college degree versus just 26.5% Black men — a gap of 18 percentage points. While more Black women are earning college degrees, their economic prospects are still highly constrained by racism and sexism and they’re less likely to reap the full economic rewards of having a degree.

Meanwhile, Black women and Black men are overrepresented among those with some college and no degree. Just over 26% of Black women have some college and no degree compared to 21% of White women. Even more troubling: the proportion of Black men with some college and no degree (24.3%) is nearly the same as the proportion of Black men with a college degree (26.5%). While college affordability (or, rather, a lack thereof) is, certainly, partly to blame for these serious imbalances, statistics like these also point to the need for institutions to examine how well they are serving Black students and whether they can provide more targeted supports.

Among those with degrees, we see considerable differences in the types of degrees earned. While the differences in associate degree attainment are minimal, we see substantial gaps at the bachelor’s degree level. Bachelor’s degree attainment rates for both White women and men are about 10 percentage points higher than they are for Black women and men, respectively (Figure 2). It should also be noted that the percentage of White women with a bachelor’s degree (25.1%) is almost the same as the percentage of Black men with any type of college degree (26.5%). While research shows that most degrees improve earnings, we know that bachelor’s degree attainment is vital, because it provides more job security and higher wages. What’s more, amid the pandemic and other recent national economic slowdowns, unemployment rates have been lowest for those with a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Degree Attainment Among Black Women and Men in the States

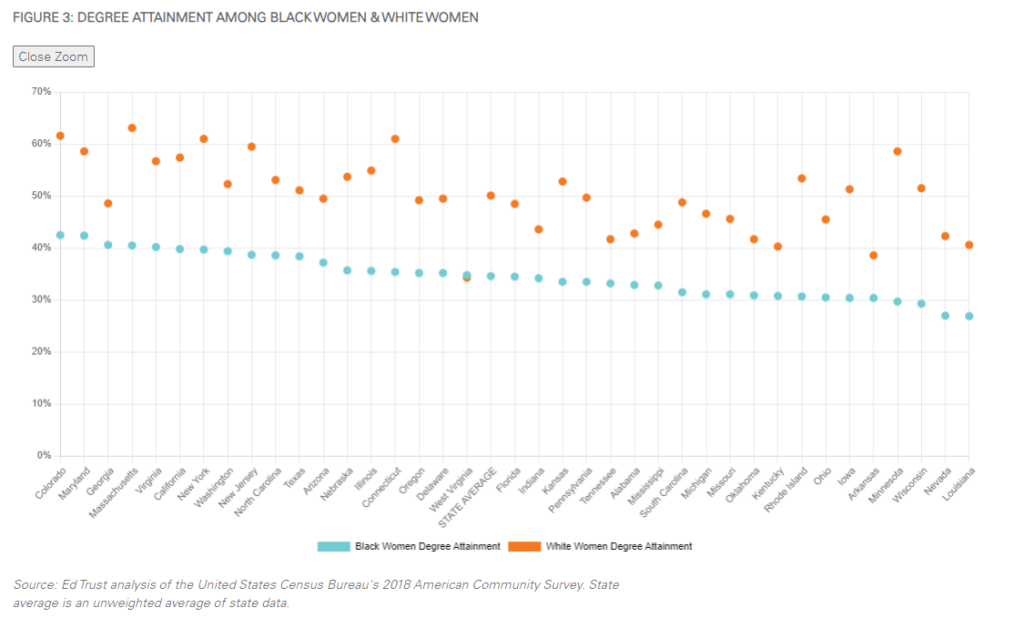

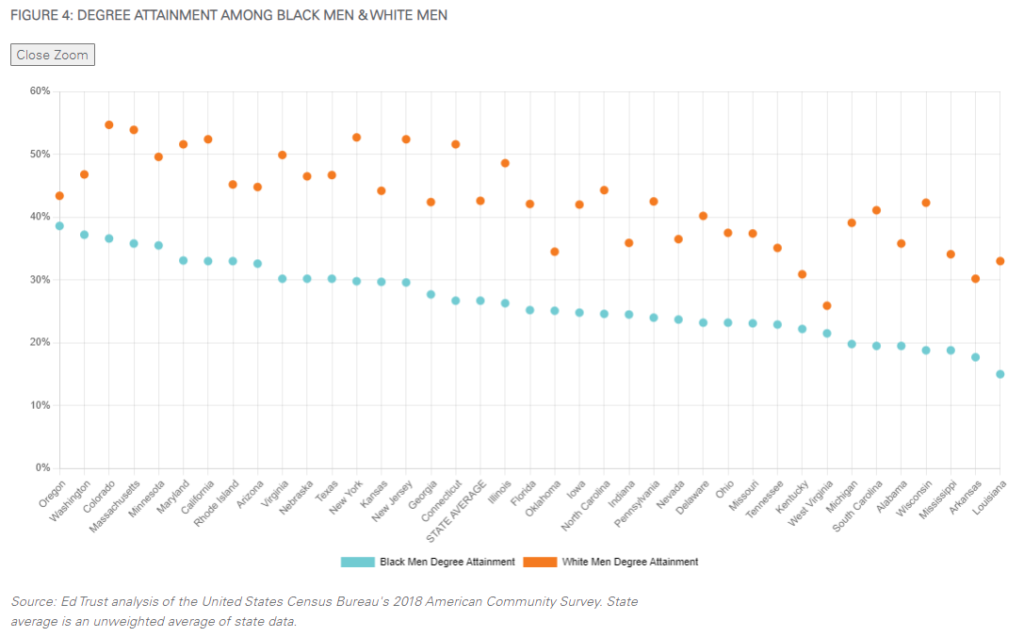

National data on attainment by race and gender reveals significant gaps between Black and White women and men: There’s a 15 percentage point gap between Black and White women and an 18 percentage point gap between Black and White men. State-level data reveals that gaps are larger in some states. In this section, we examine state-level data on degree attainment for Black women and men in 38 states. We exclude states with fewer than 15,000 Black women or Black men, since degree attainment estimates for these small samples are less reliable. First, we examine state-level attainment for Black women and attainment gaps between them and White women; then we do a similar analysis for Black men. Finally, we look at the differences in attainment between Black women and men in each state. State-level data on degree attainment for Black women and men are included in Tables A and B in the Appendix.

2018 Degree Attainment Among Black Women

In the states we examined, nearly 35.0% of Black women hold a college degree, on average. In five states (Colorado, Maryland, Georgia, Massachusetts, and Virginia), Black women have attainment rates exceeding 40.0%. (Figure 3). However, in four states (Minnesota, Wisconsin, Nevada, and Louisiana), attainment rates among Black women are below 30.0%. While Minnesota has the largest attainment gap between Black and White women, more than . Only seven states (Alabama, Kentucky, Indiana, Tennessee, Arkansas, Georgia, and West Virginia) have attainment gaps of less than 10 percentage points. West Virginia is the only state in which Black women have higher attainment than White women. But this is hardly cause for celebration; it’s largely attributable to the fact that White women in the state have extremely low attainment. The smaller gaps in Arkansas, Tennessee, Alabama, Indiana, and Kentucky are also primarily a result of low attainment among White women.

2018 Degree Attainment Among Black Men

Black men have lower levels of degree attainment than White men in every state. On average, over a quarter (26.7%) of Black men hold a college degree (Figure 4). Black men in five states (Oregon, Washington, Colorado, Massachusetts, and Minnesota) have attainment rates above 35.0%. In seven states (Michigan, South Carolina, Alabama, Wisconsin, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Louisiana), fewer than 1 in 5 Black men hold a college degree. Connecticut has the largest attainment gap between Black and White men, and six states (Connecticut, Wisconsin, New York, New Jersey, Illinois, and South Carolina) have gaps of more than 20 percentage points. Five states (Washington, Oklahoma, Kentucky, Oregon, and West Virginia) have attainment gaps of less than 10 percentage points. In Kentucky, Oklahoma, and West Virginia, the smaller attainment gaps are mostly due to lower attainment among White men.

ttainment Gaps Between Black Women and Men

In 35 of the 38 states we examined, Black women have higher levels of degree attainment than Black men (Figure 5). Rhode Island, Oregon, and Minnesota are the only states in which Black men earn degrees at higher rates than Black women. Across all states, the average gap in attainment between Black women and men is 7.9 percentage points. Mississippi and North Carolina have the widest gaps — at 14 percentage points. In one-third of the 38 states we examined, the attainment gap between Black women and men is 10 percentage points or higher. It should also be noted that these states are largely in the South.

Black Male Degree Attainment Relative to Population Representation

We also noticed a troubling trend: Degree attainment for Black men is lower in states with higher concentrations of Black men (see Figure 6). For example, in Mississippi, Louisiana, Georgia, Maryland, Alabama, South Carolina, and Delaware, the seven states in which Black men comprise at least 10.0% of the population, the average attainment rate is 22.4%. However, in states where Black men comprise less than 5.0% of the population, attainment rates among Black men are 7 percentage points higher (29.4%). Not so for Black women, whose attainment levels were relatively consistent, regardless of their proportion of the state population. This disturbing finding appears to be a product of failing K-12 schools. In the Southern states where Black men comprise at least 10% of the population (Mississippi, Louisiana, Georgia, Alabama, and South Carolina), the high school graduation rate for Black men is below 55%, versus 66% in Maryland and 61% in Delaware — Mid-Atlantic states with comparable Black male representation. A more racially diverse teaching force might be key to reversing this trend, since studies show that Black male students who have even one Black teacher in elementary school are far less likely to drop out of high school and far more likely to go on to college. Unfortunately, in all of these states, Black students represent over a third of the student body, but Black teachers comprise less than a fifth of the teaching force. In Delaware, less than 9% of teachers are Black. This might explain why in every state, except Alaska, Black students are underrepresented in advanced coursework and gifted and talented programs and disciplined at significantly higher rates than any other group. We know, for example, that teachers of color tend to have more favorable perceptions of students of color and are more likely to advocate for those students and refer them to a gifted program. Thus, this stunning lack of teacher diversity represents a failure on the part of schools to serve students who are being systematically left behind. It’s also an unfortunate reminder that for all their statements in support of Black Lives Matter, many schools still have a ton of work to do when it comes to supporting and educating the Black children within their walls.

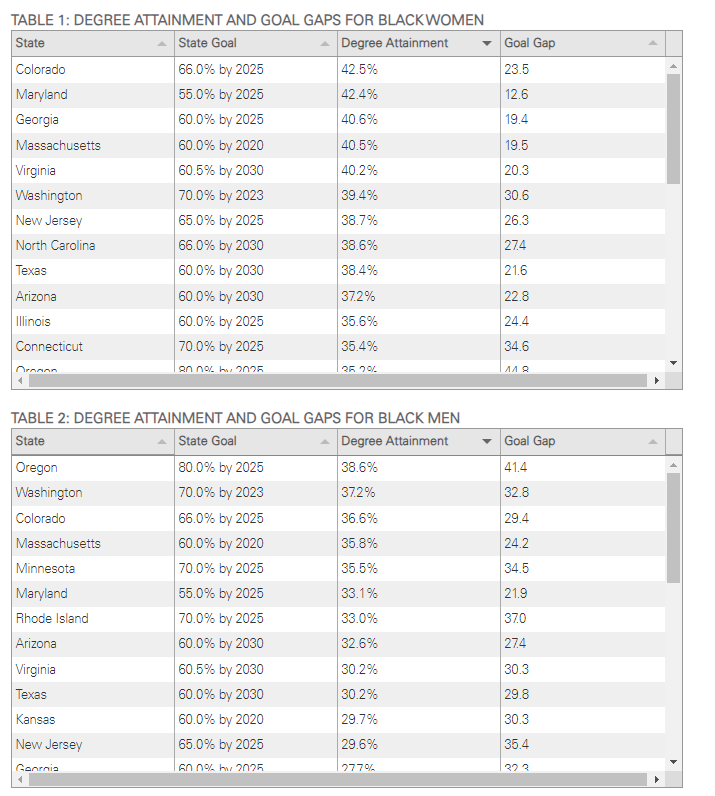

Gaps in State Attainment Goals and Degree Attainment for Black Adults

As states work toward their attainment goals in an effort to educate more residents and meet states’ growing workforce needs, we feel it’s important to examine attainment gaps by race and gender. Thirty-two of the 38 states in our analysis have set statewide degree attainment goals. But lagging attainment rates among Black women and men in each and every state suggest that most states will be hard-pressed to meet those goals (Table 1). Our analysis indicates that every state has double-digit goal gaps — i.e., the difference between the statewide goal and actual degree attainment — for Black women and men. In Oregon and Minnesota, the goal gap for Black women is more than 40 percentage points. Meanwhile, in 29 of the 32 states with attainment goals, degree attainment for Black women is missing the state goal by more than 20 percentage points.

Black men are faring even worse. In 11 states (Iowa, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Connecticut, Arkansas, Ohio, North Carolina, Oregon, Wisconsin, Alabama, and South Carolina), the goal gap for Black men is more than 40 percentage points. And in every single state, Black male attainment rates are missing state goals by over 20 percentage points.

If states are committed to hitting their goals and not leaving Black residents behind, they will need to improve the educational pipeline for Black residents. A critical look at K-12, higher education affordability, student supports and school counseling are needed to bridge these gaps.

Conclusion

An estimated 65% of all jobs now require some form of a postsecondary credential. Given this, and the fact that the U.S. demand for college-educated workers is already outstripping the supply, even amid the pandemic (and demand is only expected to grow), access to college and postsecondary training is critical, now more than ever. If we are going to revive our struggling economy, get people back to work, and emerge from the pandemic stronger than before, we’re going to need to expand college access, especially for people of color, who are a growing part of the U.S. workforce. Anything less could stifle growth for years to come.

That is why federal investment is vital. The U.S. government must increase investments in TRIO programs, which help first-generation students, students with disabilities, and students from low-income backgrounds move through the academic pipeline and have been shown to improve access for students of color. Federal investment in evidenced-based student success initiatives, like CUNY ASAP, could also help close completion gaps for students of color. Likewise, doubling the Pell Grant would have a significant impact on Black student enrollment, since more than 57% of Black college students receive Pell Grants.

States, meanwhile, should track attainment by race and gender against statewide attainment goals and establish interim metrics and targets for improvement. Investing in need-based scholarship programs that expand pathways to and through college for students of color would help boost access and degree completion. And since a high percentage of students of color start their postsecondary educational careers at community colleges, states should improve transfer and articulation to smooth the transition from two- to four-year colleges.

At the institutional level, it’s time for colleges to change their recruitment strategies and visit high schools that enroll higher numbers of students of color. Colleges should also recruit and retain more faculty of color, which has been shown to improve student success; invest in need-based, rather than merit-based, scholarships; and improve campus climate, so students of color feel welcome on college campuses.

The stakes are higher than ever. As the U.S. becomes more diverse, addressing the structural inequities that make earning a college degree disproportionately harder for students of color is more than a matter of racial and economic justice; it’s central to securing our country’s future.

About the Data

For this brief, we used data from the United States Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS) to examine degree attainment at the national and state levels. Degree attainment is defined as the percentage of adults between the ages of 25 and 64 who have a postsecondary degree (i.e., an associate, bachelor’s, or graduate degree). For the national degree attainment estimates in Figures 1 and 2, we used 2018 ACS data. This data includes adults in all states and Washington, D.C.

We calculated the degree attainment estimates for states using three-year averages of ACS data from 2016, 2017, and 2018. We used a three-year average to mitigate the influence of sampling errors and single-year anomalies for states with small populations. To avoid potential sampling errors, we excluded states from the analysis that had an average estimated population of Black women or Black men below 15,000 in 2016-2018. We included attainment data for 38 states. We excluded Alaska, Hawaii, Idaho, Maine, Montana, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont, and Wyoming.

About the Authors

A former higher education research analyst at The Education Trust, Marshall Anthony Jr., Ph.D., is now a senior policy analyst at the Center for American Progress, where he works to advance equity, affordability, and attainment in postsecondary education.

Andrew H. Nichols, Ph.D., former senior director of higher education research and data analytics at The Education Trust, spent his life fighting for equity for college students of color and college students from low-income backgrounds. He passed away in January 2021.

Wil Del Pilar, Ph.D, is vice president of higher education policy and practice at The Education Trust.