Native Students—and Non-Native Students—Deserve to Learn About the True Experiences of Indigenous People

The lack of Indigenous representation and humanity, the whitewashing of history, can deter Native students from learning.

One of my most formative childhood memories was on my first day of first grade. During free time, I made a book and bound it together with yarn or tape. I wrote and drew a tale about a unicorn with rainbow hair. My teacher was impressed and when he told my mom how smart I was, she said something like, “I know.” She seemed icy, and almost angry at the compliment. Mom knew I was literate and artistic. Her work with me began at four. I had my own library of diverse books, and she enjoyed decorating my bedroom with educational posters she made herself. I expected her to be proud when my teacher praised me, but instead she was weary. She told me that school was, “a choice,” and I didn’t understand her then, but I grew to see what she meant.

For Indigenous people of her generation, kids were often put into government funded schools after being apprehended from their families and taken from the only communities they knew. Children were treated like soldiers, called by number, and rarely admired or held. It was an assimilation effort that harmed many — and she ran away from it. Mom rarely talked about her experience, and although she returned to an academic life in her later years, she was always suspicious of what my teachers were teaching. She feared the academic space for kids prioritized whiteness in their pedagogy and content — and they did, unfortunately.

Mom was attending college to become a teacher while I was in grade school. She even did a practicum at my elementary. She kept her eyes on my curriculum and tried to make a difference. In the third grade, she analyzed my reading list and asked my teacher to substitute Huck Finn for something more contemporary with fewer slurs. “Your teacher is not teaching one book by a Black man or woman,” Mom said.

It hurt to have the book switched out. The rest of the class read and discussed Mark Twain while I was left alone to read The Cay, by Theodore Taylor, a book arguably just as problematic. Mom’s good work allowed me to see the racism and lack of diversity in the classroom, but it felt isolating to be the only student with a mother fighting to improve the system. Those who speak out against the biased status quo are often treated like the problem. I felt like the problem child, so when I got to high school, I asked her to let me fight for myself in my own way. She acquiesced and understood I was growing and becoming a woman. “The fight is yours now,” she said.

We had our deepest conversations by the river, right before we prayed. Before I started my junior year, Mom took me to the water, and I prayed for school to be better and more fruitful. A prayer to the river is like a hope placed in the current. Not every prayer gets answered, but it’s nice to put a little tobacco in water and imagine better.

In seventh grade, my social studies teacher gave a long-winded lecture about diversity. It was an embarrassing effort on his part. He talked to students about “tolerating” difference, as if Native people were something to be tolerated. It offended me, and instead of speaking up I checked out. I stopped doing assignments, and started skipping school, which led to administrative intervention. I showed passive resistance to a system I could not change.

They eventually placed me in an alternative school where I could advance toward graduation, completing workbooks at my own pace. The work felt stale. My peers and I were often treated like “bad” or “lost” kids, when we were just young adults struggling with authority or homelife. I eventually dropped out and it took about a decade to return and earn my GED. By the time I graduated, I was very grown, very autonomous, and strong enough to survive in the academic realm and advocate for equal treatment, diversity, and equity.

I love books and writing more than almost anything. My career required an advanced degree and study. The lack of representation, the lack of humanity during my studies, deterred me from a life of learning for a long time.

I’m a best-selling author now, and sometimes I mourn time lost hiding from academia. I am a courageous woman like my mother, who couldn’t be deterred long from learning spaces, but I know a lot of people who dropped out and never returned. I know a lot of people who found educational spaces too violent and ignorant to learn in.

I still take tobacco to the river and carry hope for better. I’ve become a mother, and my sons are at college and elementary ages. Sometimes I check out their reading lists, or hear how history is being taught, and it gives me worry. While things are moderately better for young people learning, there is still so much left to do.

I want my sons to see themselves in books, and for our true history to be represented, and I want them to know social change is possible, and that earth science should include components for environmental action, and hope. I want my children to learn more about the world and humanity in school — I’d like them to know about equity and houselessness, and American democracy and varied opinions on colonization.

The world opens wide with difference when you let it exist in the classroom without burden, shame, or biases. School should be a space of inspiration. All my children are artists and deep thinkers at heart. I think of my mother when they tell me about the ignorance they face as Indigenous learners — I think of myself when I see them uninspired with the content they’re being taught.

My second youngest recently had a week learning about the presidents. They had a mini focus on Lincoln, and my child talked about Lincoln’s transgressions against Indigenous people. He mentioned the mass hanging of 38 Dakota men. The teacher was impressed, and encouraging, but the classroom wasn’t prepared to have that conversation yet. They moved onto other presidents, and my son, the avid reader, brought up the transgressions of those other men. I was proud to hear about it.

My hope is that learning spaces can become more ready for stories, for difference, for growth and the truth we Indigenous people live with each day. I want all students to feel seen, and for all marginalized stories and experiences to be just as valid as the centered work we’ve been taught for so long.

Terese Mailhot is the New York Times bestselling author of Heart Berries: A Memoir.

Each piece in this series is accompanied by relevant resources and book recommendations provided by one or more of our partners, with input from the authors.

Established in 2006 by Dr. Debbie Reese of Nambé Pueblo, American Indians in Children’s Literature (AICL) provides critical analysis of Indigenous peoples in children’s and young adult books. Dr. Jean Mendoza joined AICL as a co-editor in 2016. A primary purpose of AICL is to help everyone know who Native people are. That knowledge can help readers understand why Native people object to being misrepresented. Though authors do not set out to deliberately misrepresent Native people, it happens over and over again. Information is the only way to counter those misrepresentations. AICL contributes this information through analyses of children’s books, lesson plans, films, and other items related to the topic of American Indians and how this topic is taught in school. AICL also provides an annual essay that highlights the year’s events, and a list of the year’s best books.

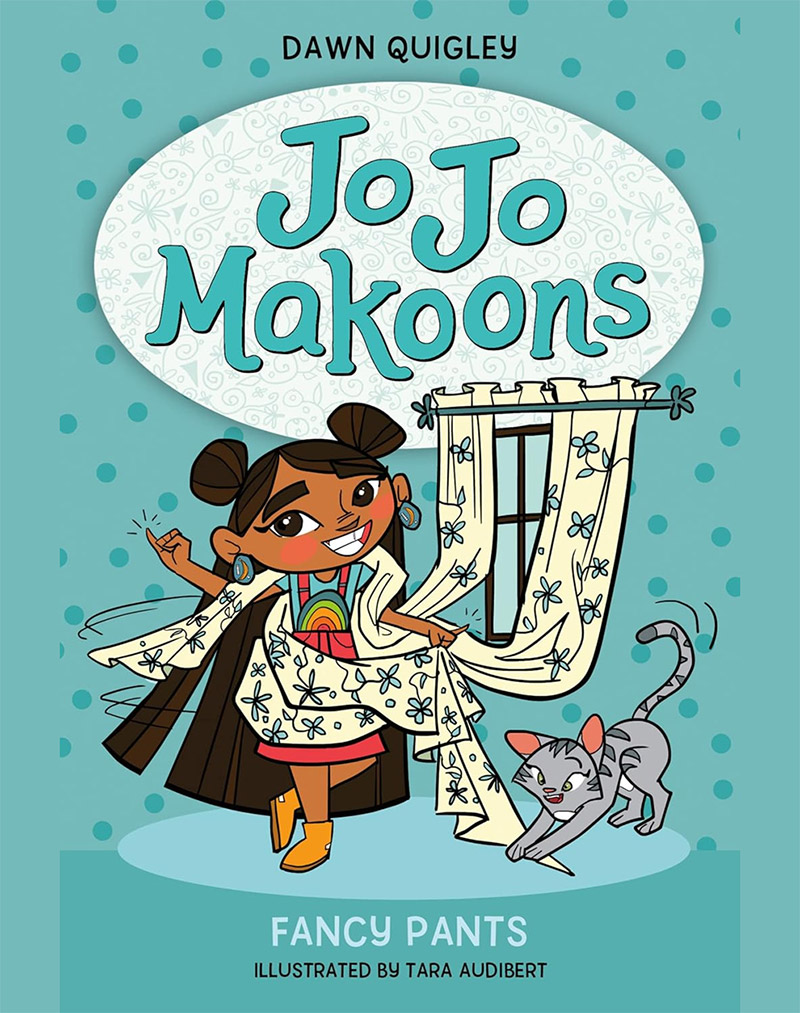

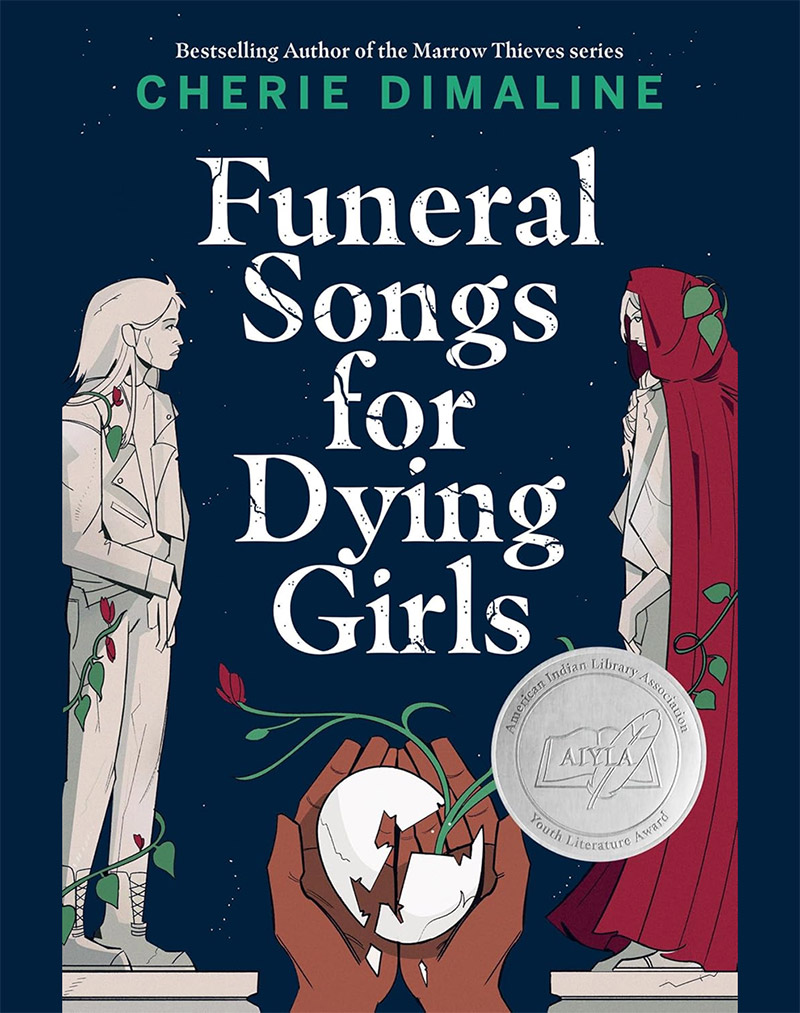

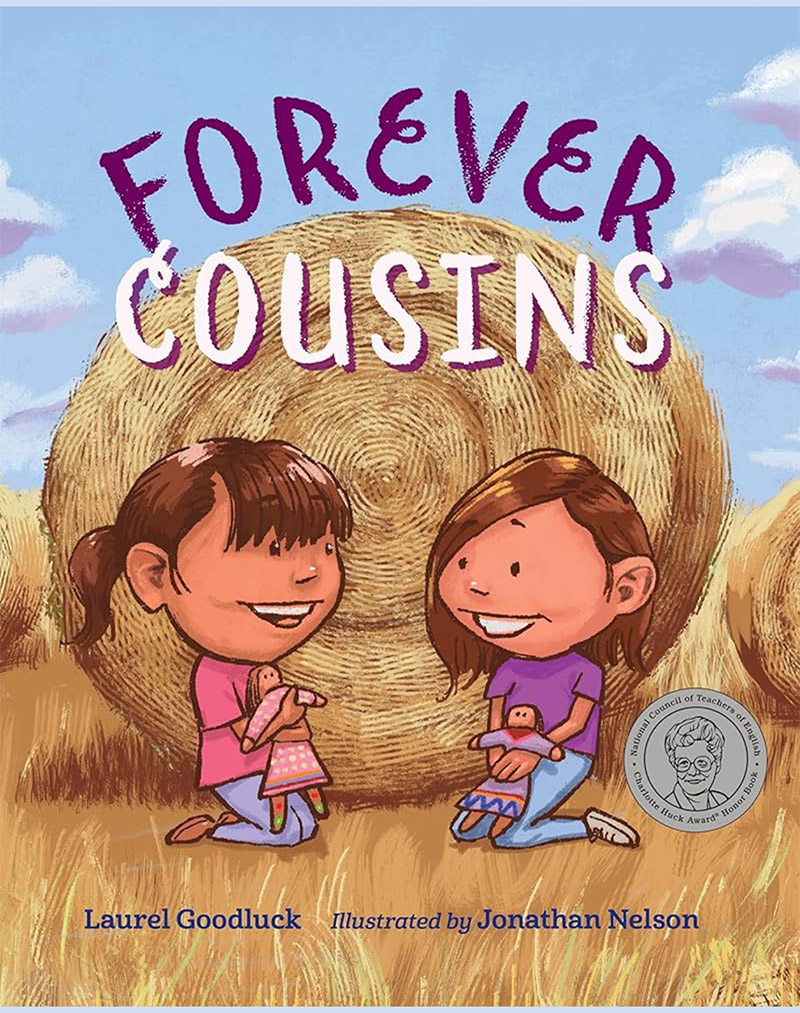

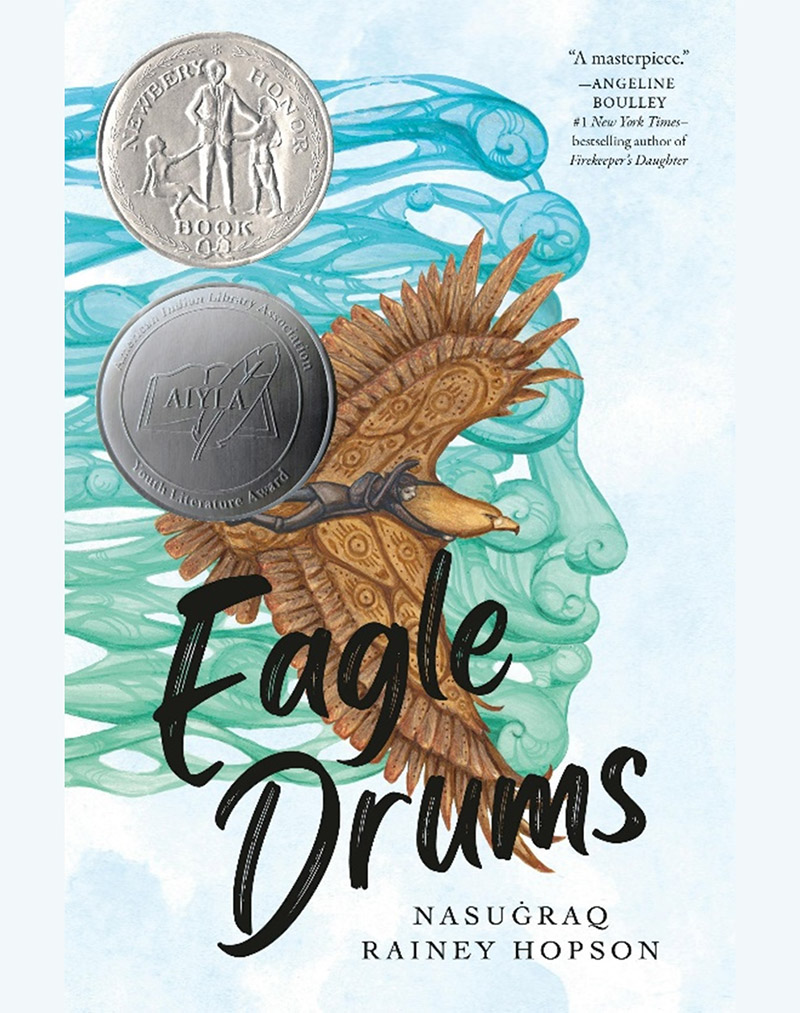

The American Indian Library Association (AILA), affiliate of the American Library Association (ALA), is a membership action group that addresses the library-related needs of American Indians and Alaska Natives. Members are individuals and institutions interested in the development of programs to improve Indian library, cultural, and informational services in school, public, and research libraries on reservations. AILA is also committed to disseminating information about Indian cultures, languages, values, and information needs to the library community. AILA cosponsors an annual conference and holds a yearly business meeting in conjunction with the American Library Association annual meeting. It publishes the American Indian Libraries Newsletter twice a year. Awarded biennially, the American Indian Youth Literature Award (AIYLA) identifies and honors the very best writing and illustrations by Native Americans and Indigenous peoples of North America. The recommendations below are each winner or honor book recipients of the 2024 American Indian Youth Literature Awards.