Equal Is Not Good Enough

When it comes to providing children with a high-quality education, money matters. Yet, the U.S. education system is plagued…

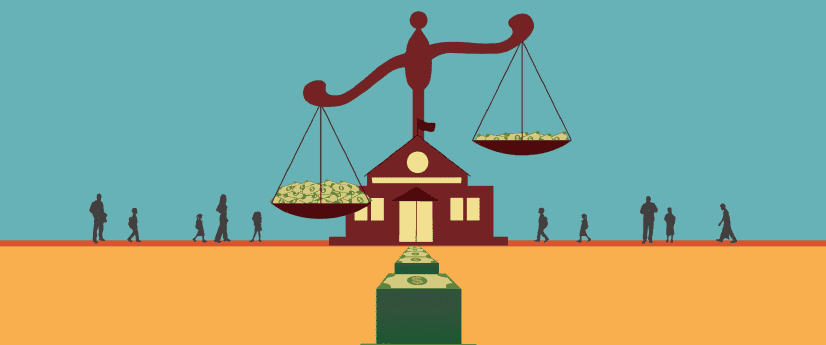

When it comes to providing children with a high-quality education, money matters. Yet, the U.S. education system is plagued with persistent and longstanding funding inequities — with the majority of states sending the fewest number of resources to the districts and schools that actually need the most resources.

To ensure that school districts had the resources to meet students’ needs due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government infused nearly $200 billion into state school funding coffers. While this money may help temporarily erase some of the persistent inequities in school funding, it won’t last forever. State leaders need to address the systemic, longstanding inequities in school funding systems now, so that the so-called “fiscal cliff” will not impose the most disruption in high-need communities.

For more than 20 years, The Education Trust has been analyzing school finance data, contributing to a rich body of research and analysis on the persistent gaps in revenue. This report updates that analysis, looking closely at patterns across and within states and for specific student groups. It includes new analysis comparing funding between the country’s districts with the most and fewest English learners, who represent a sizeable share of the overall student population. It is also accompanied by a new, interactive data tool that, for the first time, drills down to district and specific school-level data and reveals that those inequities persist.

Here are some of the most notable findings:

Brief

Full Brief: Equal Is Not Good Enough

Brief

Advocacy Brief

Technical Appendix

Equal is Not Good Enough

Press Release

School Districts That Serve Students of Color Receive Significantly Less Funding

Report

ACCESS GRANTED – School Funding Between Schools in Districts

Fact Sheet

5 Things to Advance Equity in State Funding Systems

Website

What Is the State of Funding Equity in Your State?

Website

FundEd

Report

Common Sense & Fairness Recommendations – Ed Build