Equal Is Not Good Enough

An Analysis of School Funding Equity Across the U.S. and Within Each State

When it comes to providing children with a high-quality education, money matters. Yet, the U.S. education system is plagued with persistent and longstanding funding inequities — with the majority of states sending the fewest number of resources to the districts and schools that actually need the most resources.

To ensure that school districts had the resources to meet students’ needs due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government infused nearly $200 billion into state school funding coffers. While this money may help temporarily erase some of the persistent inequities in school funding, it won’t last forever. State leaders need to address the systemic, longstanding inequities in school funding systems now, so that the so-called “fiscal cliff” will not impose the most disruption in high-need communities.

For more than 20 years, The Education Trust has been analyzing school finance data, contributing to a rich body of research and analysis on the persistent gaps in revenue. This report updates that analysis, looking closely at patterns across and within states and for specific student groups. It includes new analysis comparing funding between the country’s districts with the most and fewest English learners, who represent a sizeable share of the overall student population. It is also accompanied by a new, interactive data tool that, for the first time, drills down to district and specific school-level data and reveals that those inequities persist.

Here are some of the most notable findings:

- Across the country, districts with the most students of color on average receive substantially less (16%) state and local revenue than districts with the fewest students of color, and high-poverty districts receive 5% less state and local revenue than low-poverty districts. The districts with the most English learners receive 14% less state and local revenue, compared with districts with the fewest English learners.

- While national summary data shows clear regressive funding patterns, state-by-state data tells a more nuanced story, in which state and local revenue is allocated progressively for some groups of students, but not others.

- The policies that states set up to fund their districts and schools can address or exacerbate inequities. In many states, state revenue is not allocated in a way that fully counteracts inequities in local funding

Recommendations

It Is important to understand what the data says about funding inequities and the specific policies that could address those inequities. Context-specific recommendations can lead to windows of opportunity to change the policies that govern how states fund districts.

When pushing for school funding reform, advocates should work toward achieving the policy recommendations noted below that align with challenges in specific states.

State & Local Combined

An equitable funding structure is an important foundation. There are three key features of equitable state and local funding systems:

- State and local funding should be allocated so that higher-need districts serving more students from low-income backgrounds and English learners receive more funding; and that districts serving the most students of color do not receive less funding.

- States should send more funding to districts that have less ability to raise local revenue, and states should limit property-wealthy districts’ ability to create new inequities through exorbitant amounts of additional local funds.

- States should also ensure that the funding allocated is adequate to support a rigorous, high-quality education program for all students, particularly English learners, students from low-income backgrounds, and students of color

State

State leaders should provide more funding to high-need districts than to property-rich, lower-need districts. They can do this by including additional funding for students from low-income backgrounds, English learners, and students with disabilities in the education funding structure. In addition, state leaders should ensure that state revenue fully makes up the difference between what the district needs and what it is reasonably able to raise in local revenue.

Local

State leaders should ensure the contribution asked of high-wealth districts is an appropriate fair share and that the funding burden borne by low-wealth districts is reasonable. They should also address inequities in local sources of funds (including property wealth and income) by requiring localities to fully fund an expected local share of education funding based on their ability to raise revenue. For example, there should be a required local contribution based on a standard tax rate that will yield a larger local share in property-rich districts than in property-poor ones. State leaders should also limit property-wealthy districts’ ability to raise and spend exorbitant amounts of additional local funds, thus creating new inequities.

Federal Considerations

Education funding comes from a combination of federal, state, and local funds — but the vast majority (about 90%) comes from states and localities. Therefore, state leaders must address long-standing inequities in their school funding systems and close state and local funding gaps so that all students have the resources they need to thrive.

However, the federal government plays an important role in funding education, too. In addition to the recent influx of ARP dollars allotted to schools, there has been much more interest in recent years in increasing the amount of federal funding available to support education — specifically by increasing Title I funding; ensuring that additional funding is allocated to provide substantially more resources to high-poverty districts; and incentivizing states to develop more equitable state funding policies. Future proposals to improve federal fiscal equity should ensure that school funding adequately meets student needs and is targeted so that the states, districts, and schools that need the most resources receive the most funding.

What Did We Find?

States’ school funding systems should ensure that districts receive significant additional state and local funding to support students from low-income families and English learners. In addition, school funding systems should ensure that districts serving high concentrations of students of color receive at least as much state and local funding as other districts. Unfortunately, that is not what the data reveals. Instead, a varied picture emerges in which too many districts that have greater needs — no matter how you define it — do not receive more state and local funding.

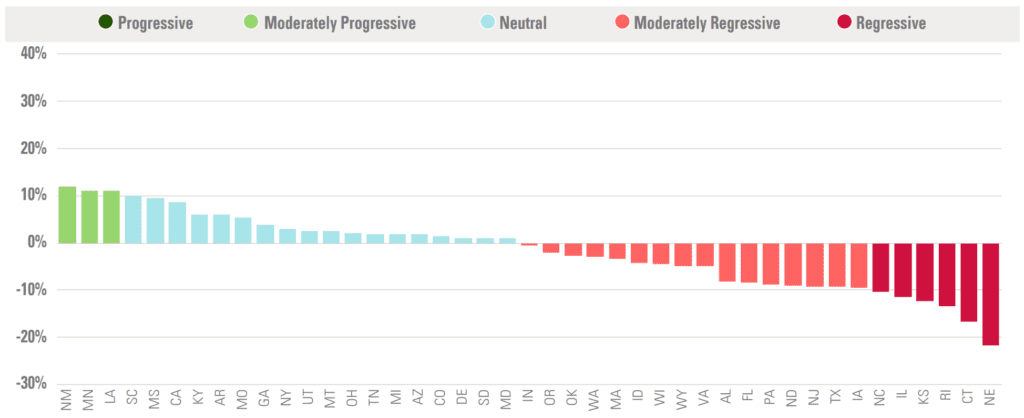

Finding 1: Nationwide, Districts With the Most Students of Color Receive Less State and Local Revenue Than Districts With Fewer Students of Color

Across the country, districts with the most students of color on average receive substantially less (16%) state and local revenue than districts with the fewest students of color. That’s about $2,700 less per student — and in a district with 5,000 students, that gap could mean $13.5 million in missing resources.

Why does this matter? Students of color have long been denied fair school funding because their communities have been long denied fair opportunities to build wealth due to systemic racism. State school funding systems should address these disparities by ensuring that districts with the most students of color receive a combination of state and local funding that is at least as much the amount that districts with the fewest students of color receive.

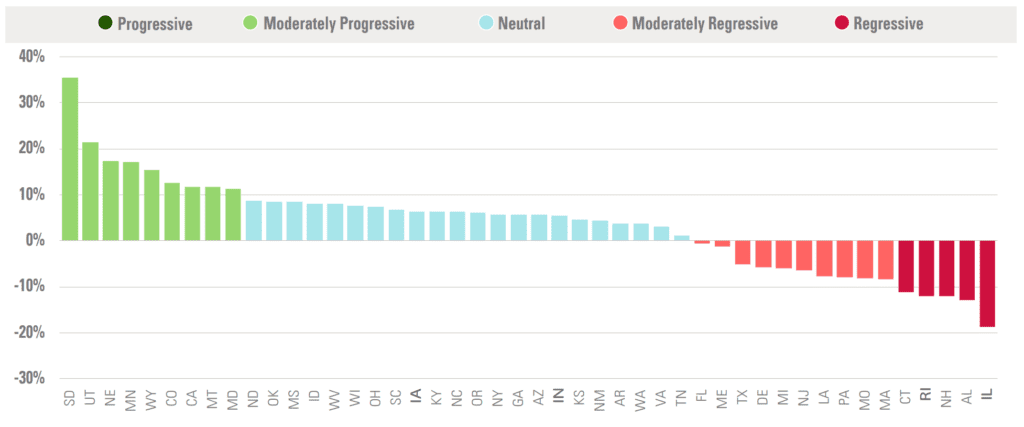

FIGURE 1: Gaps in State and Local Revenues per Student Between Districts Serving the Most and Fewest Students of Color, 2018-2020

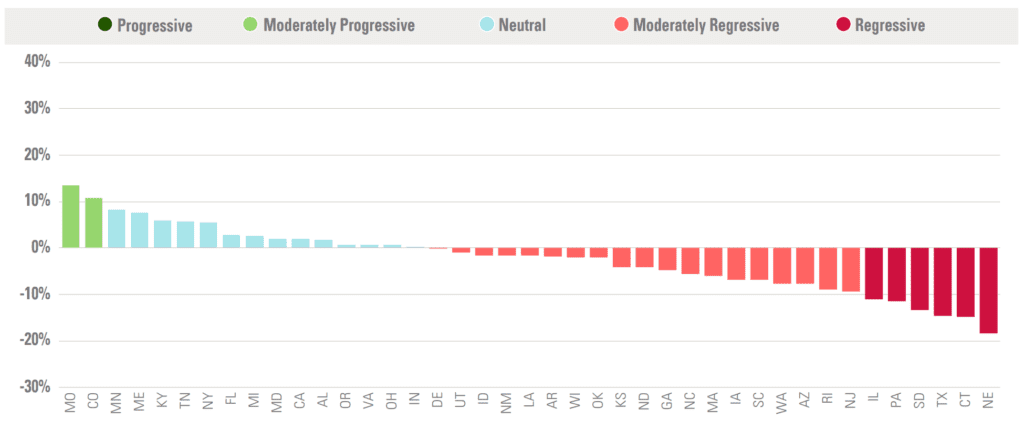

Finding 2: Districts With the Most English Learners Also Receive Less State and Local Revenue Than Districts With Fewer English Learners

Across the country, the districts with the most English learners receive 14% less state and local revenue, compared with districts with the fewest English learners. That leaves districts with higher needs for resources — including bilingual educators and instructional materials — with $2,200 less per student than districts with lower needs.

Why does this matter? Multilingual learners are an incredibly diverse group of students — their socioeconomic status and sociocultural background vary just as much as their home languages and English proficiency. They represent a sizeable share of the overall student population — almost 12 million children ages 5 to 17 speak a language other than English at home, and 5 million students are classified as English learners, who currently account for about 10% of the K-12 student population.

FIGURE 2: Gaps in State and Local Revenues per Student Between Districts Serving the Most and Fewest English Learners, 2018-2020

Finding 3: Despite Clear Evidence That Students From Low-Income Backgrounds Need More Resources To Thrive Academically, High-Poverty Districts Receive Less State and Local Revenue Than Low-Poverty Districts

Across the country, high-poverty districts receive on average 5% less (about $800 per student) state and local revenue than low-poverty districts. This may seem like a small difference, but it’s not — most schools with 500 students could hire at least three more teachers with that additional funding. What’s more, equal funding should not be the goal, because equal is not good enough.

Why does this matter? Research shows that students from low-income backgrounds benefit more both in the short and long term, when their schools have additional funding. Schools and districts that serve more students from low-income backgrounds should receive more funding to help ensure that students have rich educational experiences that prepare them to excel in post-secondary opportunities at least as well as peers from more affluent backgrounds.

FIGURE 3: Gaps in State and Local Revenues per Student Between Districts Serving the Most and Fewest Students from Low-Income Backgrounds, 2018-2020

Finding 4: The Gaps in State and Local Revenue Between Districts With the Most and Fewest Students of Color or English Learners Tend To Be Worse Than the Income-Based Gaps

While there are regressive state and local funding gaps in 22 (of 43) states between districts with the highest and lowest percentages of students of color and 25 (of 41) states between districts with high and low percentages of students learning English, there are only 15 (of 46) states with regressive gaps between districts with high and low percentages of students from low-income backgrounds.

Why does this matter? Any disparities in school funding that see higher-need districts receive less funding are unacceptable. But it’s particularly problematic for districts serving high concentrations of English learners or students of color to have funding gaps that are two to three times larger than the gaps for districts with high percentages of students from low-income backgrounds.

Finding 5: States Where State and Local Revenue Is Progressively Allocated for One Group of Students, Do Not Necessarily Have Progressive Allocations for Other Groups of Students

Some states — like Maryland and Minnesota — are doing better than other states in ensuring that high-need districts receive more funding to support students’ needs. In each of these states, the districts with the most students from low-income backgrounds, students of color, or English learners receive more state and local funding than the districts with the smallest shares of each of group of students.

There are also states that are doing well for one group of students but not others. For example, state and local funding in California is more targeted to higher-poverty districts, but it is not as well targeted to districts with the most students of color or English learners.

Why does this matter? State policy drives inequities in state and local funding. If state funding is not sufficient to counteract inequities in local funding between high- and low-need districts, then states should change their policies to increase targeting of state funds to low-wealth districts. If state funding is sufficient to counteract inequities in local funding between districts serving the most and fewest students from low-income backgrounds, but not between districts with the highest and lowest percentages of students in other groups, then state policy should change to increase targeting of state funds to districts with more student need. States also have the power to put limits on the extent to which inequities in local funding can arise.

Finding 6: State Revenue Is Not Allocated in a Way That Fully Counteracts Inequities in Local Funding

Across the country, districts with the most students from low-income backgrounds, students of color, or English learners receive substantially less local revenue than other districts. These inequities should be corrected by the additional state funding that high-need districts receive compared with low-need districts. But they are not. Instead, districts with high percentages of students from low-income backgrounds, students of color, or students learning English receive less total state and local revenue.

Why does this matter? Local revenue is mainly derived from local property taxes, which is inherently inequitable. Different communities have different property values, and districts in property-wealthy communities will always have an easier time raising more money at similar tax rates. Due to systemic racism, communities of color have been long denied fair opportunities to build wealth. The legacy of housing discrimination still shows up in school funding patterns today. While some states have funding formulas with mechanisms that counteract the inequities in local revenue that exist across districts, many states fall short. Total state and local revenue should be progressive, even if local revenue is not.

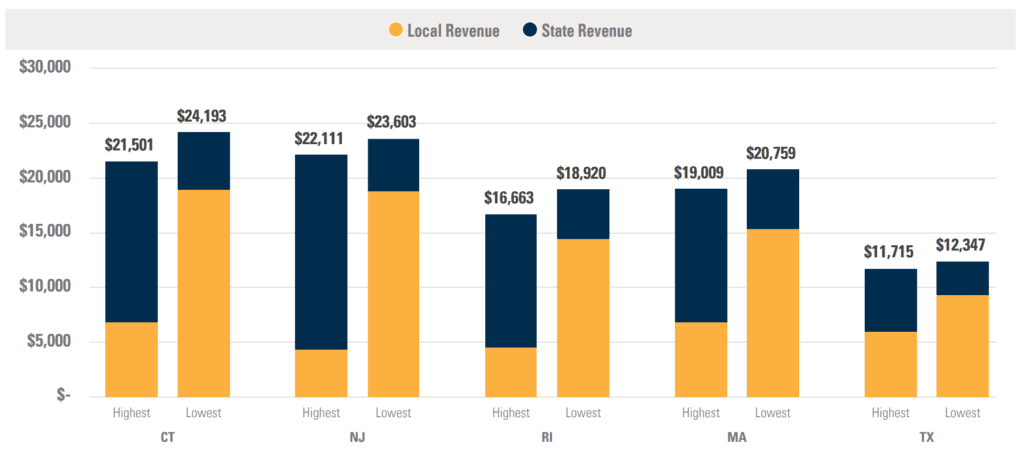

FIGURE 5: State and local revenue by source of funds in the highest and lowest poverty districts in selected states, 2018-2020