How Black Women Experience Student Debt

Forty-five million Americans collectively owe $1.7 trillion in student loan debt, and women hold nearly two-thirds of it. But because of the gender pay gap, women are more likely than men to have trouble paying off their debt.[1] Black borrowers are the group most negatively affected by student loans, in large part because of systemic racism, the inequitable distribution of wealth, a stratified labor market, and rising college costs. Because Black women exist at the intersection of two marginalized identities and experience sexism and racism at the same time, they make less money and often need to borrow more to cover the cost of attendance, and struggle significantly with repayment.

Drawing on data from federal sources and our National Black Student Debt Study, How Black Women Experience Student Debt shows how the student debt crisis is the result of failed and intentionally racist policies.

The student debt crisis among Black women is the result of failed and intentionally racist policies. Policymakers must act. The Biden administration and Congress should take the following actions to end the student debt crisis and make college affordable for future students:

- More than 80% of the participants in the “Jim Crow Debt” study think the federal government should cancel all student debt. The Education Trust supports cancelling at least $50,000 of federal student debt and opposes limiting eligibility for cancellation by income, loan type, or degree type (e.g., undergraduate vs. graduate degree).

- In the absence of total broad-based debt cancellation, the Biden administration should make significant improvements to income-driven repayment (IDR) plans to make monthly payments more affordable, reduce negative amortization, and shorten the time-to-forgiveness window.

- To make college affordable, Congress should double the Pell Grant and create federal-state partnerships to make public college debt free.

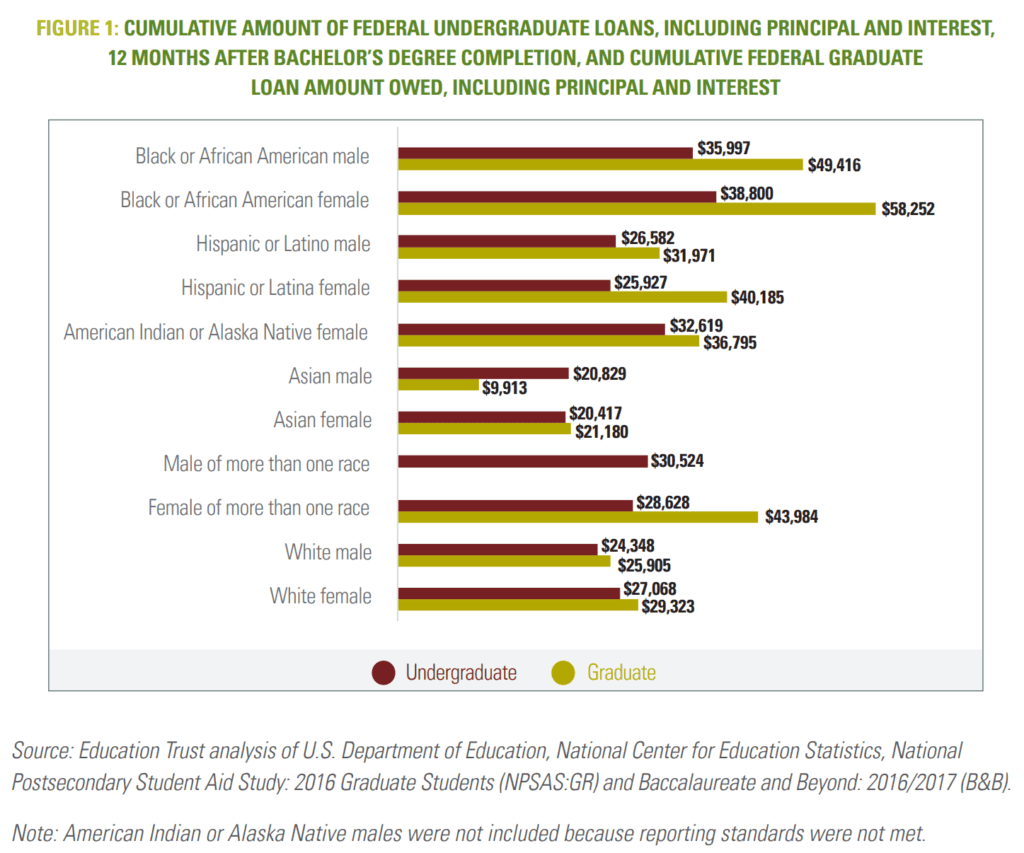

Black Women Are Burdened the Most by the High Cost of College

College costs have risen dramatically over the past several decades, as state funding for public colleges and universities has declined.[2] Financial aid hasn’t kept pace with college costs, which are now unaffordable for most Americans. The high cost of college is particularly burdensome for Black women, who because of structural racism and sexism, have fewer financial resources to pay for a higher education and little choice but to borrow higher amounts.[3] A year after completing a bachelor’s degree, Black women hold more student debt than any other group — with an average of $38,800 in federal undergraduate loans. Black female borrowers who attended graduate school hold an average of $58,252 in graduate loans. Despite the enormous cost of going to college, Black women are still pursuing a higher education because to achieve their academic and professional goals and improve the financial situation of their families, they need a degree.

As a borrower going by the pseudonym of Belle, who borrowed $171,000, noted:

“How do you tell someone that they cannot reach for their dream or their highest potential because they can’t afford it? You’re going to do what you need to do to sit in that room and that class, even it means being burdened with the consequences of what you took out to get where you’re at.”

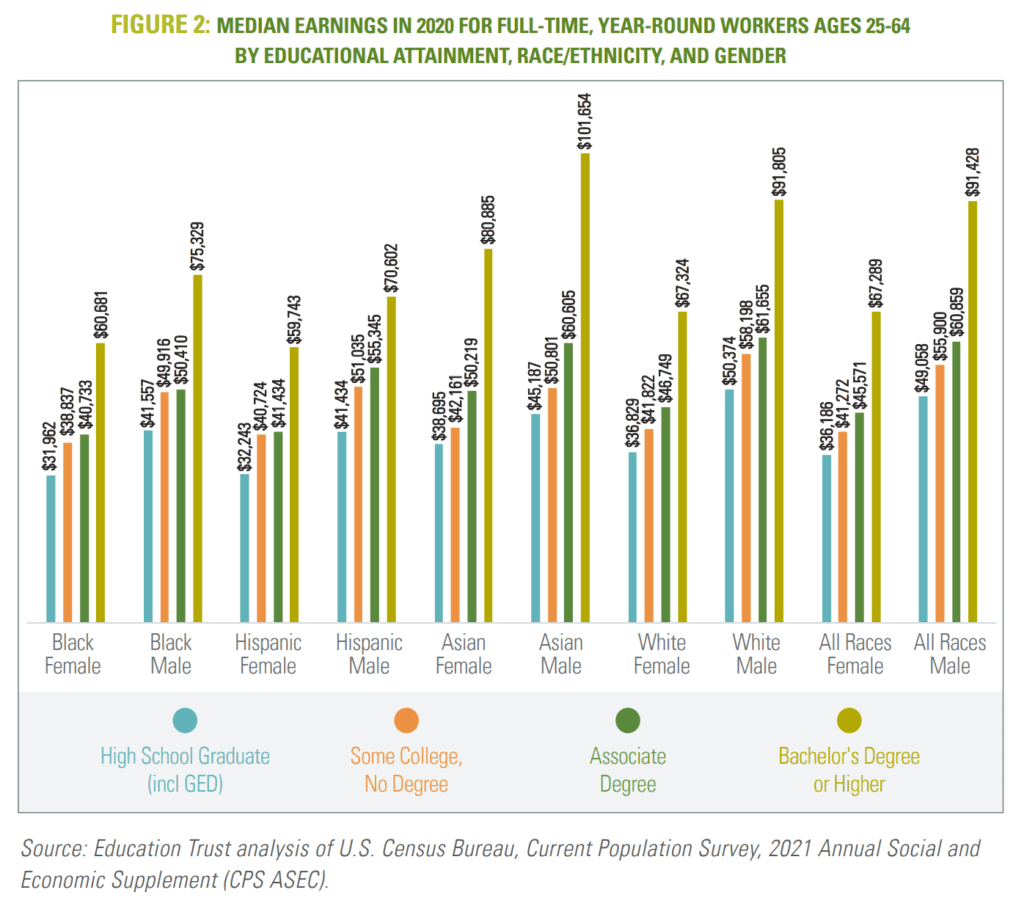

For Black Women, More Debt Does Not Equal a Higher Salary

Black women also get a lower financial return on their college investment than men of all races and most women, except for Latinas with a bachelor’s degree or higher, according to the data.[4] Black women ages 25-64 who hold a bachelor’s degree or higher and work full time and year-round had median earnings of $60,681 in 2020, compared to $91,805 for White men, $75,329 for Black men, and $67,324 for White women. That sharp earnings disparity does serious harm to Black women who are trying to pay off their debt.

That was true for a borrower using the pseudonym of Florence, whose income, even with a master’s degree, was too low to make a dent in the more than $239,000 she borrowed:

“I came out of my first master’s program, and it was repayment time, and I only had a $25,000 salary. How can I pay this much money in loans?”

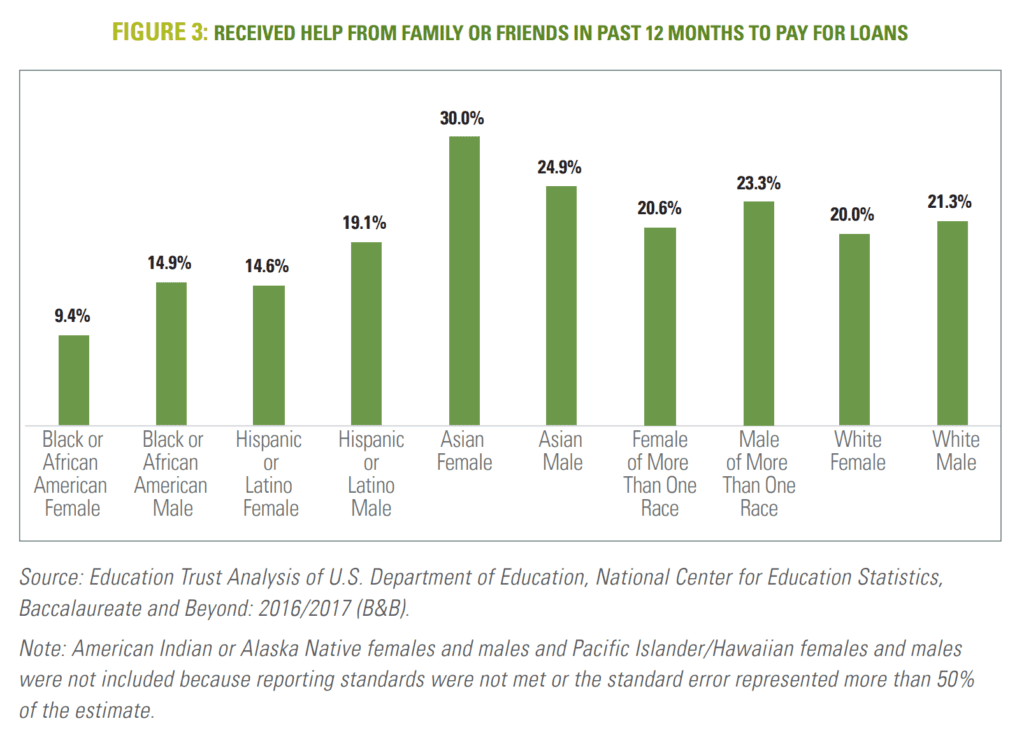

The Racial Wealth Gap Leaves Black Women With Few Resources to Repay Student Debt

The crisis in Black women’s ability to repay student debt is larger than just wage disparity. Black women’s ability to repay student debt is not only hindered by lower wages, but by a lack of generational wealth. In 2019, the median Black household had just $24,100 in wealth next to $188,200 for the median White household.[5] For single Black women, wealth is nearly nonexistent. In 2019, the median net worth of a single Black woman under 35 was only $101, compared to $22,640 for a single White man, $6,470 for a single White woman, and $1,550 for a single Black man.[6] Obtaining a higher education does not erase that gap. In fact, the median Black household headed by a person with a bachelor’s degree has less wealth than the median White household headed by a person without a high school diploma. Because Black families have less wealth and lower earnings, Black borrowers — and Black women in particular — are less likely to receive financial support from family or friends to help cover the costs of college or student debt.

Many Black Women Are Student Parents

Not only do structural barriers make it harder for many Black women to repay their student loans, but Black women are more likely to be student parents. The added costs of raising a child, the high cost of child care, and the financial insecurity faced by many student parents can lead them to borrow more for college.[7] Student parents borrow more than non-parents, and mothers, particularly single mothers, borrow the most.[8] Black student parents borrow more than any other racial or ethnic group.[9]

A borrower going by the pseudonym of Lisa, who owes $115,000, described her experience as a parent in repayment like this:

“I was, I think, 22, on my third kid, barely had money to feed them […] and pay bills. And then [the loan servicer] kept sending letters, and I was just like, ‘I can’t pay them. […] I don’t know what they want from me. I don’t have the money.’ And then I had moved, so I guess they had sent these court papers to a different address. And then, next thing I know, my job was like, ‘Hey, we’re garnishing [your paycheck] for this money.’”

Black Women Are Struggling to Manage Repayment

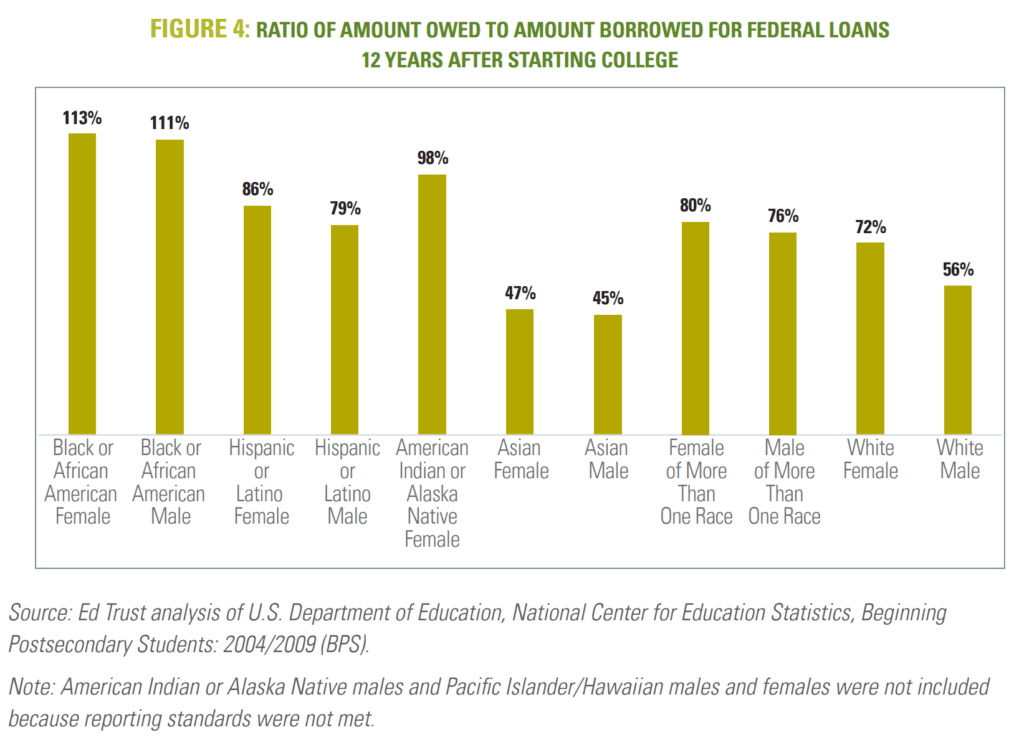

Many Black female study participants shared they struggle to make monthly payments and are deeply concerned that they will never be able to pay off their student debt. Twelve years after starting college, Black women owe 13% more than they borrowed compared to White men, who, by then, have paid off 44% of their debt. Most of the Black women in the study had used forbearance or deferment to postpone payments; some had defaulted when they lacked the means to pay.

A borrower using the pseudonym of Maisha, who borrowed $10,000 while pursuing a bachelor’s degree she did not complete, described how defaulting negatively affected her credit:

“Once it affect[ed] the credit score, it affected the types of jobs I could apply for. It affected a lot of different avenues for me. I definitely couldn’t ask for another loan […]. I couldn’t [get] a car loan. I would have to pay for a car that was probably 20 years old and on its last legs, but then I would have to come out of pocket for that, so I was mostly tethered to the jobs that were around my bus line or around the BART line, so that I could go anywhere I needed to go [and] back and forth to work on my bus pass.”

1) Kevin Miller, Deeper in Debt: Women & Student Loans (American Association of University Women, May 2017), https://www.aauw.org/resources/research/deeper-in-debt.

2) Victoria Jackson and Matt Saenz, States Can Choose Better Path for Higher Education Funding in COVID-19 Recession (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 17, 2021), https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/states-can-choose-better-path-for-higher-education-funding-in-covid.

3)Daan Struyven, Gizelle George-Joseph, and Daniel Milo. Black Womenomics: Investing in the Underinvested. (Goldman Sachs, March 9, 2021), https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/pages/black-womenomics-report-summary.html.

4) Marianne Bertrand and Sendhil Mullainathan, Are Emily and Greg More Employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A Field Experiment on Labor Market Discrimination (National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper Series, July 2003), https://doi.org/10.3386/w9873.

5) Neil Bhutta, Andrew C. Chang, Lisa J. Dettling, and Joanne W. Hsu, “Disparities in Wealth by Race and Ethnicity in the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances,” FEDS Notes (Washington, DC: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, September 28, 2020), https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.2797.

6) Emily Moss Broady Kriston McIntosh, Wendy Edelberg, and Kristen E., “The Black-White Wealth Gap Left Black Households More Vulnerable” (The Brookings Institution, December 8, 2020), https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/12/08/the-black-white-wealth-gap-left-black-households-more-vulnerable/.

7) Lindsey Reichlin Cruse et al., “Parents in College By the Numbers” (Institute for Women’s Policy Research, April 11, 2019), https://iwpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/C481_Parents-in-College-By-the-Numbers-Aspen-Ascend-and-IWPR.pdf.