Top 5 Things to Know about Texas Community College Funding

Community colleges have long provided education and job training opportunities to Texans of all ages and backgrounds. In 1973, the last time the legislature studied the state’s funding for community colleges, only 28% of jobs required some level of education beyond high school. Today, that percentage has grown to 68%, making community colleges a cornerstone of the state’s future.

Since lawmakers established it in the most recent legislative session, the Texas Commission on Community College Finance has held three public meetings. As Commission members have heard invited testimony from a variety of leaders and experts, we’ve been following closely and hosting meeting recaps to share key themes.

Looking for a quick introduction to Texas community college finance? Here are five foundational things to know:

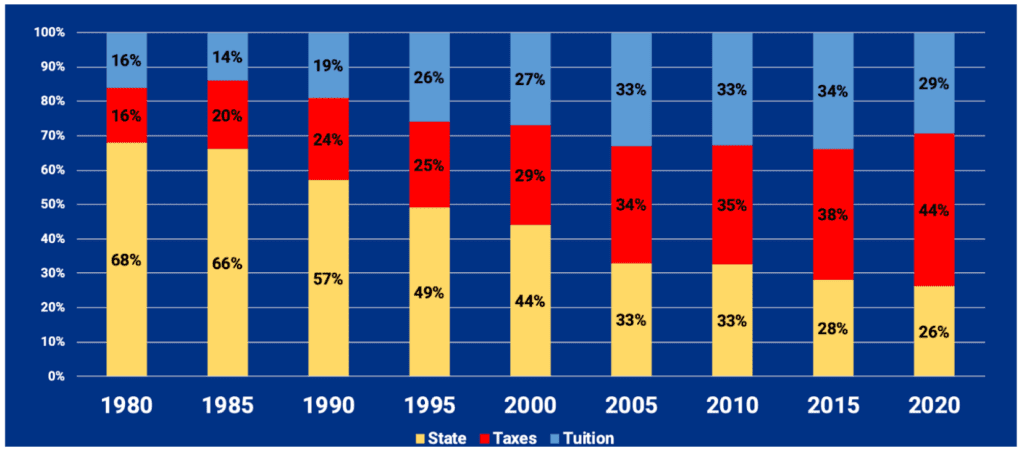

1. The state isn't paying for community colleges the way it used to.

In 1980, state investment represented 68% of community college funding; in 2020, the state’s share was down to just 26%. This steady decline has led community colleges to increasingly rely on local property taxes and student tuition and fees to fulfill their diverse mission. For most community colleges, this includes dual credit offerings in high school, transfer preparation to four-year institutions, career preparation, short-term workforce training, and non-credit adult education.

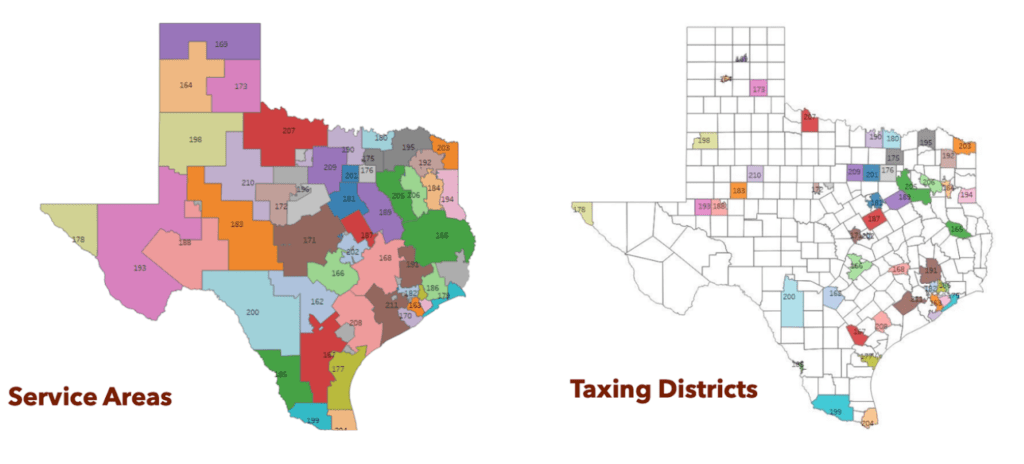

2. Local property taxes vary widely, resulting in widely different tuition costs and services.

Local voters must approve a property tax to fund the community college that serves their area, yet nearly one-third of the state’s property value does not currently contribute at all. Among those taxing districts that do contribute, local property tax rates vary by 650% (from 5.6 cents for the Blinn College taxing district to 39.27 cents for the South Plains College taxing district). This variation leads tuition rates for students to vary by nearly 250% (from $1,200 at Dallas College to $4,400 at Blinn College).

3. The funding formula does not account for differing student needs and the costs to successfully meet them.

Unlike our K-12 finance system, which adjusts for multiple student characteristics (student income, disability status, language proficiency, etc.), none of Texas’ community college funding components are designed to support or reward institutions for meeting the needs of diverse learners. This includes academically or economically disadvantaged students, who make up a growing majority of those enrolled.

4. Performance-based funding is not currently sufficient to impact student outcomes.

“Student Success Points” account for roughly 10% of state funding, but less than 3% of all community college revenue. What’s more, the value of each point changes every two-year cycle based on the state’s total funding level for community colleges, making this revenue source relatively unpredictable and unlikely to generate the kind of additional resources that might influence a community college’s decision-making or outcomes.

5. State financial aid programs don’t prioritize community college students.

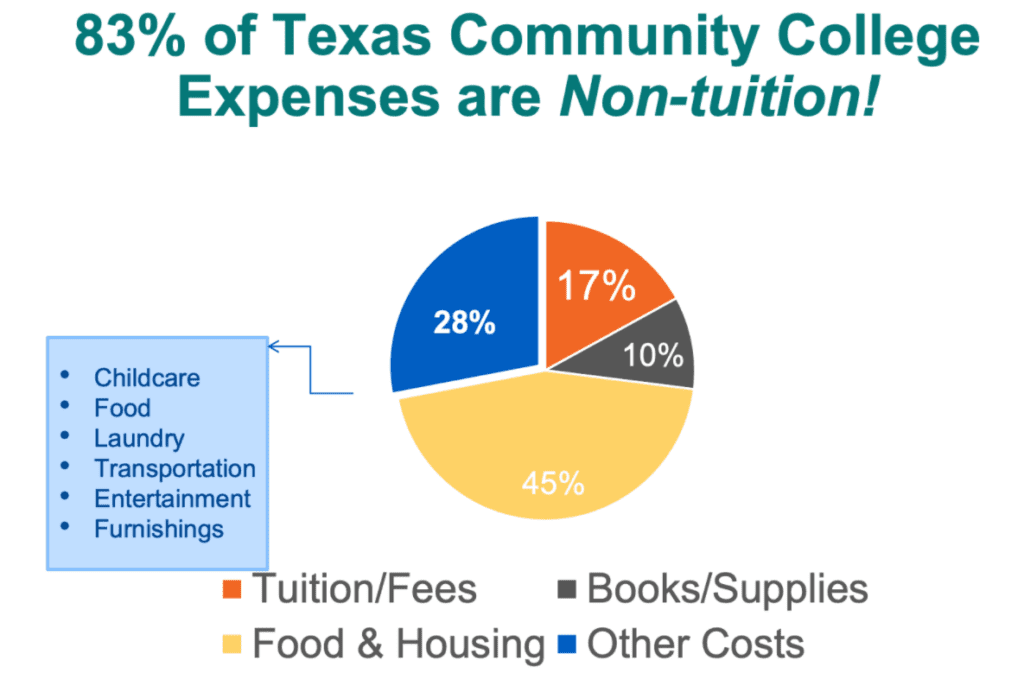

Despite having the same enrollment, the state devotes 10 times more to TEXAS Grants for students attending public four-year colleges ($866M in the current biennium) than to Texas Educational Opportunity Grants for students attending public 2-year colleges ($88 million in the current biennium). When you consider that more than 80% of community college costs are non-tuition (food, transportation, child care), resulting financial shortfalls lead to basic needs insecurity that can easily throw students off their path to completion.