Without Affirmative Action, It’s Back to Basics

This spring, the US Supreme Court is widely expected to ban the consideration of race in college admissions, ending a practice that—while well-intentioned—never actually succeeded in ensuring that racial demographics at the nation’s selective colleges came close to resembling those of the college-aged population. Some say the loss of this form of affirmative action will be no loss at all, either for colleges or for their students. the Georgetown University Center for Education and Workforce’s recent research shows, to the contrary, that a lot is at stake with this decision, and the consequences will be far-reaching.

Colleges could partially claw back some racial/ethnic diversity with class-conscious admissions, but they won’t come any closer to proportional representation.

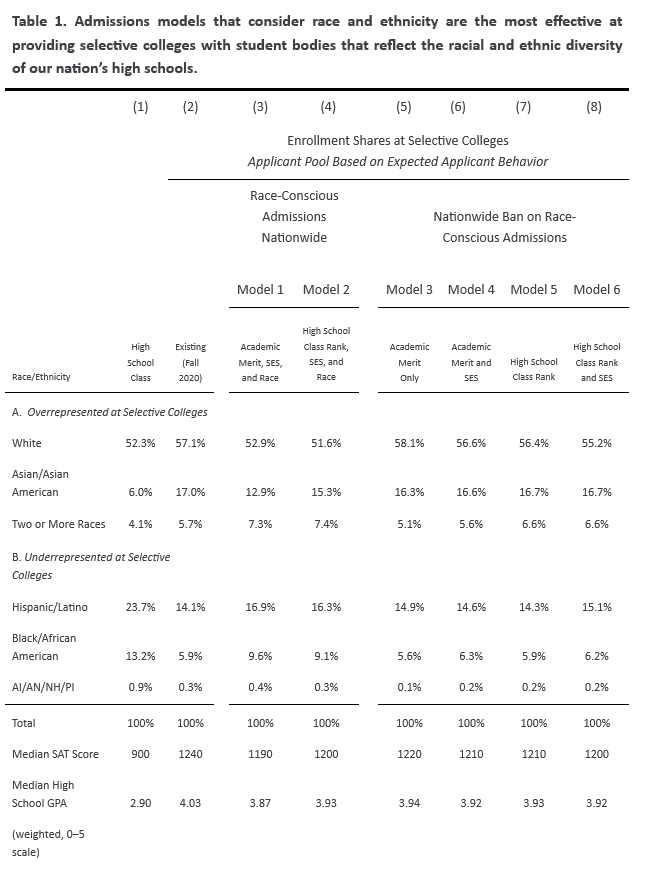

In anticipation of the court’s forthcoming decision, we created six models to estimate the impact that different approaches to admissions could have on racial/ethnic diversity at the nation’s most selective colleges. (We also examined the impact of these models on socioeconomic representation; readers should see the report for that analysis.) Four of these models assumed the adoption of admissions factors other than race/ethnicity, such as academic merit, class rank, and socioeconomic status (SES), either separately or in combination. Two models included consideration of race/ethnicity to provide a sense of what is at stake if race-conscious admissions are prohibited.

We found that some class-conscious alternatives to race-conscious admissions could modestly increase representation for Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino students, but doing so would require eliminating admissions preferences for legacy applicants, children of donors, student athletes, and other privileged groups. Still, even if colleges abandon those practices, class-conscious alternatives would likely decrease representation for American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander students. Only admissions policies that expand rather than remove the consideration of race can result in student bodies that come close to mirroring the composition of the graduating high school class (Table 1). This result would require far more selective institutions to use race-conscious admissions than do at present (currently, only about 60% do).

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis of data from the US Census Bureau and Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey (CPS) October Education Supplement, 2020; US Department of Education, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), 2021; and US Department of Education, High School Longitudinal Study of 2009 (HSLS:09), restricted use data, 2022. Previously published in Carnevale et al., Race-Conscious Affirmative Action: What’s Next, 2023.

Notes: All results are generated using survey weights that account for the sampling design of the Current Population Survey October 2020 Education Supplement and the HSLS:09, and for sample attrition in follow-up survey rounds of the HSLS:09 study. AI = American Indian; AN = Alaska Native; NH = Native Hawaiian; and PI = Pacific Islander. The sample is restricted to selective college applicants. In columns (4) through (8), the sample is adjusted to account for the expected change in composition after the introduction of a nationwide top 10% admissions policy and/or the repeal of race-based affirmative action. In columns (5) through (8), 60 percent of institutions are assumed to adopt alternative admissions policies in response to a nationwide ban, reflecting the fact that some institutions operate in states that already impose a ban on race-conscious admissions and others currently choose not to consider race in admissions. Academic merit is defined as a combination of high school GPA, college entrance exam scores, and AP exam participation and performance. Numbers may not sum to 100 percent due to rounding.

Our results are promising in the sense that class-conscious alternatives offer some potential to advance racial/ethnic diversity. Importantly, however, they also indicate that the efficacy of class-conscious alternatives hinges on enacting other sweeping admissions reforms. In particular, following a ban on race-conscious admissions, students from marginalized racial/ethnic groups are likely to become even more underrepresented at selective colleges if institutions preserve admissions preferences that tend to benefit upper-class White applicants—as we expect them to do, at least in the short term. Achieving the diversity that our models suggest is possible would mean suspending these practices.

Empirical evidence from states with affirmative action bans suggests how unlikely it is that selective colleges will be able to maintain current levels of racial/ethnic diversity without race-conscious admissions. Research has shown that representation gaps for Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, and Native American students—that is, the gap between their representation in selective colleges and their representation in high schools—grew in almost all affected states after bans took effect. That doesn’t bode well for representation at the national level.

Maintaining racial/ethnic diversity through class-conscious admissions or expanded recruitment efforts will be financially and politically expensive.

Although selective colleges may be able to use class-conscious admissions to claw back some racial/ethnic diversity, doing so will be an uphill battle. For one thing, colleges that use class-conscious admissions to generate racial diversity may face lawsuits challenging those practices as racially discriminatory, as occurred in a recent suit filed against a selective high school in Virginia.

For another, successfully recruiting students from low-income family backgrounds is expensive. Research shows that attracting applicants from this talent pool and giving them admissions preferences isn’t enough to ensure they enroll—socioeconomically disadvantaged candidates need considerable financial support to make attending a selective college a real option. To support a substantial increase in low-income student enrollment, many selective colleges will need to reevaluate their financial priorities and put significant energy into fundraising for scholarships. Increasing the funds available for federal Pell grants would help, but it won’t likely offset the full cost associated with increased financial need.

Regardless of the options available, backlash is coming to selective colleges. Elitism is bad politics on both the right and the left, and selective colleges have built their brand on elitism. They once used SAT scores to hide behind the cover of “merit,” but the SAT’s regime is crumbling, with fewer schools requiring SAT scores and fewer students submitting them. Once race-conscious affirmative action falls, the pressure will be on to ban legacy admissions; Oregon Senators Merkley and Bowman have already introduced a bill proposing to do just that. The pressure will also be on to pass the College Transparency Act, ensuring that all postsecondary institutions are held to standards of transparency and accountability.

Removing the option of affirmative action in colleges puts the spotlight on K–12 as the primary stage for education reform.

Race-conscious affirmative action was intended as a stop-gap—a way of compensating for the disadvantages associated with racial bias and discrimination until we as a society could root out those societal ills at their source. Racial injustice continues to limit educational and economic opportunity, and with race-conscious admissions no longer an option, policymakers will have to go back to basics. In this case, that means targeting reforms to early childhood education and K-12 schools—the institutions that define young people’s early lives and their opportunities into adulthood.

Of course, K–12 reform has been on the docket for a very long time, with little lasting success. No Child Left Behind reached for federal accountability, but subsequent legislation has returned much authority to the states. This April marked 40 years since A Nation at Risk sounded the clarion call for education reform. Meanwhile, educational disparities by race/ethnicity and class have held strong, as reflected in still-substantial test score gaps between White and Black/African American, as well as White and Hispanic/Latino, students.

These gaps have been allowed to persist in part because the Supreme Court decided in 1973 that there is no federal constitutional right to equitable educational funding. Many state constitutions guarantee the right to an adequate education, however, so state-level litigation remains fertile ground for advancing educational equity. Some of the most promising policy leadership has also been happening at the state level. California Governor Gavin Newsome’s Cradle-to-Career System, for example, aims to connect data sources across the state to help young people and their families map their futures across K–12, college, employment, and social services. It represents the kind of all-one-system approach we need to make sure every young person in America has the opportunity to thrive.

All in all, a ban on race-conscious admissions will make America’s selective colleges less representative of the racial/ethnic diversity in our country, at least in the short term. It will also change the scope of the conversation about educational and economic opportunity. Effectively addressing persistent racial and economic injustice in America without affirmative action will require pivoting from stop-gap solutions to a comprehensive, system-wide approach that levels the playing field long before college.

Anthony P. Carnevale is a research professor and director of the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce.

Zachary Mabel is a research professor of education and economics at the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce.

Kathryn Peltier Campbell is associate director of editorial policy and a senior editor/writer at the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce.