#COVID19PBL Educators Connecting Across the Distance and Exhibiting Anti-Racist Values

My school’s transition to distance learning was much like a lot of principals. We rushed to pass out technology, upload assignments to Google Classroom, and anguished about how we would prepare students for standardized tests. Somewhere during the process, I calmed down enough to realize I was operating in ways that did not align to my core values as a leader, but most importantly as an educator. I began to reflect on the purpose of education, what learning matters in this current landscape, how could we go deeper than packets, and for me, and perhaps most importantly, how do I evidence my core anti-racist values?

As I began to think about how best to get me and my school back in line with our core values and steer us, and maybe others, away from the race to pick up school and simply move it to an online space, I thought about the words of Bettina L. Love in her recent Ed Week article, “We now have the opportunity not to just reimagine schooling or try to reform injustice but to start over.” I realized we have the opportunity to do what is right, now, and it should push us to ensure we do “this” right when school buildings reopen. There are no bells ringing, state tests looming over our heads, and we aren’t even locked within the walls of the school building.

Leaning on Love’s message, I got to work, thinking about how we might offer teachers and students something drastically different. My students are largely Black and Latino students who rarely see themselves in the curricula most often used in schools. At the same time, so much curriculum is prescribed and teachers have a diminished voice in shaping what their students will do. As a social-justice focused principal, I work to involve my teachers in curriculum decisions and wanted to bring this idea to educators across the nation. The idea of an interdisciplinary COVID-19 curricula project, therefore, began with a late night blog post, “A School Principal’s Ponderings during a Pandemic.” I asked educators to join me on developing lessons, creating tasks, and providing resources centered around the pandemic. And #COVID19PBL was born.

Over a 10-day period,150 educators from across the nation joined a shared document and built an incredible resource. Materials are organized by subject area and phases of a project-based learning (PBL) unit. PBL is a vehicle to increase student engagement and motivation, which is especially important now when those usually responsible for their motivation are intermittently available. There are links to additional resources, articles, and multimedia. Educators will find examples of essential questions, various content ideas, and to use the resource, educators might explore the resources individually, as a team, or as a whole school. There are options for planning templates and a few sample unit plans. Educators will find modifications for English learners and tips for using a trauma-sensitive approach, given the triggering nature of this topic.

While we know the importance of state standards, we centered our students by having a clear definitive focus on social emotional and academic learning, culturally responsive teaching, and social justice. PBL, in particular, gives teachers the opportunity to harness the power of culturally responsive teaching (CRT). Zaretta Hammond writes, CRT “recognizes students’ cultural displays of learning,” uses “cultural knowledge as a scaffold,” and promotes “effective information processing,” all while teachers are “being in relationship and having a social-emotional connection” with students (2014). Naturally, harnessing this power, PBL allows for students to do the heavy lifting, sparks curiosity, and promotes authentic applications of content knowledge. Additionally, PBL empowers students to address social issues. Through PBL, students get to own their learning in ways other processes do not allow.

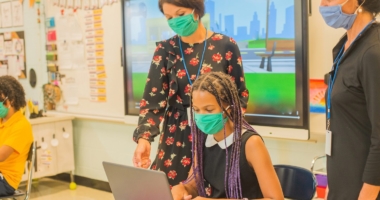

In response to our work, we realized simply creating these tasks was not enough. We had to see what students would produce. We had to know if what we created resonated with students. To do this, we planned to have an end-of-year public student exhibition. There, students would share their learning, their process, and any products they created with other students and educators. We assembled a core team, including Share Your Learning, to plan the logistics, recruited interested schools, and held a virtual nationwide exhibition on May 29. One student from New York, named Ricardo, presented about his environmental justice and health disparities project. This is what it is all about.

For me and other leaders who believe in culturally sustaining, anti-racist pedagogy and curriculum, #COVID19PBL represents an opportunity to think differently about school. We must not be innovative during school closures and then go back to the status quo when students return to buildings. As we look forward to returning to school, we must hold on to the possibilities a project like #COVID19PBL showed could happen.

When we return to school, we must finally address the dehumanizing aspects of schooling that disenfranchise students and leave too many languishing in under-resourced systems. We must emphatically stop speeding through content, tracking students, and forcing them into instructional practices that render them invisible. We must prioritize student centered learning, deeper learning, student voice and learning agency. These are just are a few ways we can create anti-racist schools. As the Iroquois lived, we must build schools for the benefit of the seventh generation into the future. We will be judged accordingly. Let’s make the right call.

Joe Truss is committed to dismantling white supremacy culture in schools. He is the principal of Visitacion Valley Middle School in San Francisco. He also writes about leadership on his blog, CulturallyResponsiveLeadership.com and provides racial equity consulting.