Gainful Employment, Take Two

The U.S. Department of Education’s latest proposal for regulating career education programs shows that officials mean business when they bring higher education experts together next week in another attempt to define “gainful employment.”

The revised definition is tougher than what it proposed just several months ago, and it adds two additional measures that career education programs must satisfy to demonstrate they are actually preparing students for well-paying jobs: student loan default rates by program (not institution) and the total loan repayment amount for all borrowers in a program. The department’s prior definition only used debt-to-earnings (meaning loan payments couldn’t exceed a certain percentage of graduates’ incomes) as an accountability measure. This was incomplete because it didn’t capture students who drop out, which left programs with high dropout rates off the hook.

Students need accountability measures that will protect them from the unthinkable — that some career education programs aren’t fully committed to preparing students to succeed. Some are more interested in growing their bottom line, even if it is at the expense of sacrificing students’ futures. For more than three years, there has been a hard, drawn out battle in Washington, D.C., over how to define what current law means when it permits students to use federal financial aid for programs that “lead to gainful employment in a recognized occupation.” It’s past time that these career education programs demonstrate outcomes in exchange for using federal money.

Students need accountability measures that will protect them from the unthinkable — that some career education programs aren’t fully committed to preparing students to succeed. Some are more interested in growing their bottom line, even if it is at the expense of sacrificing students’ futures. For more than three years, there has been a hard, drawn out battle in Washington, D.C., over how to define what current law means when it permits students to use federal financial aid for programs that “lead to gainful employment in a recognized occupation.” It’s past time that these career education programs demonstrate outcomes in exchange for using federal money.

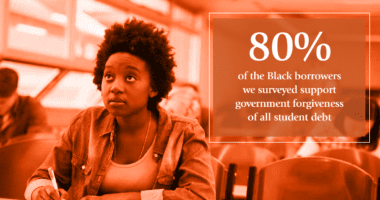

The addition of the program default rate and the repayment rate measures, as proposed by the department, would ensure this much-needed accountability. Programs with high student default rates, either in one year or over the course of several years, would lose eligibility to receive federal aid. Programs whose participants owe, collectively, the same or more on their federal student loans than they did at the beginning of the year, for three straight years, would also lose their eligibility to receive federal aid. (For a detailed analysis of the new measures, check out Ben Miller’s piece at Ed Central.)

Since we have been down this road before, it is too early to call a victory for students. Should this new definition become part of the final regulation, students will receive some guarantees that they’ll get the high-quality education for which they are paying. And taxpayers will get some assurance that their tax dollars have been wisely invested in federal student aid programs.