The FAFSA Divide: Getting More Low-Income Students to Apply for Aid

Almost 20 percent of students with family incomes low enough to qualify for a Pell Grant never even apply. And many more students who qualify for other types of financial aid are missing out, too, having never submitted their Free Application for Federal Student Aid. According to our analysis of new data from the U.S. Department of Education, students in high-poverty districts — those with the greatest need — are submitting the FAFSA at lower rates than their peers in wealthier districts — who are more likely to go to college, regardless of financial aid.

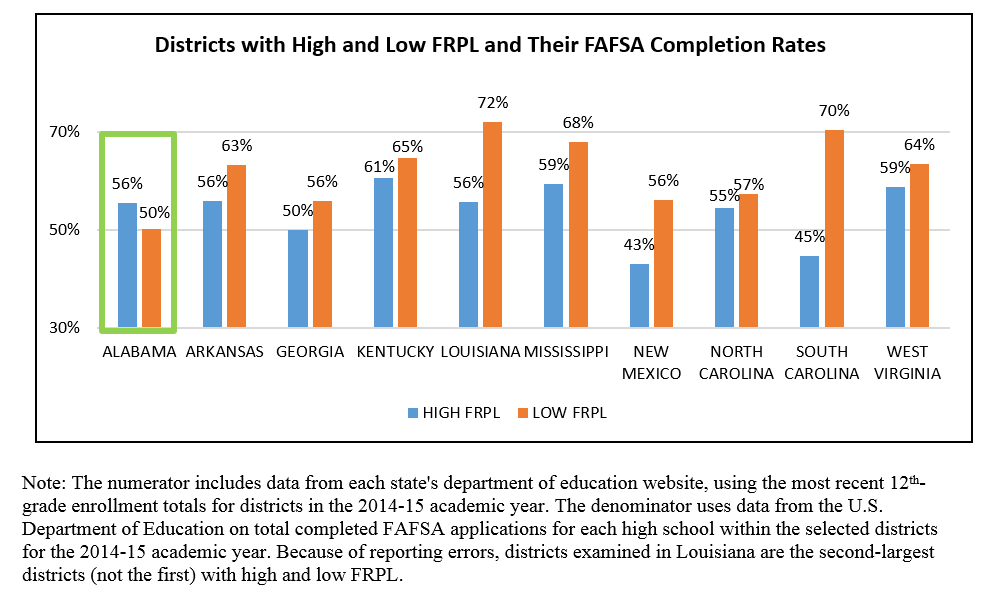

The chart below lists states with 25 percent of students living in poverty and shows the 2014-15 FAFSA completion rates for the largest school districts (more than 300 enrolled seniors) with the highest percentages of students who are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch (FRPL), an indicator of poverty, and the lowest percentages.

In 9 out of the 10 states that we examined, wealthier districts had higher FAFSA completion rates than high-poverty districts. Take for example, East Baton Rouge Parish in Louisiana, which is only 11 miles away from Zachary Community School District, but has double the rate of low-income students and has a much lower FAFSA completion rate than its peer.

Unfortunately, too many of these students are closing the door on college before ever learning about the financial aid available to them. This can lead to grave consequences, from never applying to college to taking on considerable amounts of unnecessary student debt. More concerning, for those who do decide to apply for financial aid, some don’t finish the application because they find it to be too complex, long, or difficult to understand.

However, thanks to FAFSA completion campaigns across the US, this is beginning to change. For instance, in Alabama, North Carolina, and Kentucky, efforts to increase rates are paying off as the divide in FAFSA completion rates between low- and high-income districts is closing. In Alabama, completion rates are higher in the district with the highest percentage of low-income students. Similarly, in North Carolina and Kentucky, completion rates in low-income districts are only a few percentage points behind higher income districts, even though these districts have large socioeconomic differences among their students.

Additionally, the Tennessee Promise, which provides funding for students who go to community college and mentors students as they apply for college and financial aid, has had positive effects on FAFSA completion rates. This year, 60 percent of high school seniors in the state submitted their FAFSA by March 1, compared with 42 percent last year.

Other innovative initiatives taking place include:

- Michelle Obama’s FAFSA Completion Challenge, which is a competition aimed to gain the attention of students who have not yet applied for federal aid;

- The Illinois Student Assistance Commission, which helps school districts identify seniors who are eligible but have not applied for aid and provides guidance to those students as they complete their applications;

- The U.S. Department of Education’s FAFSA Completion Initiative, which is an expansion of the Illinois model that partners with state agencies to help districts identify who has not applied for aid; and

- High schools throughout the U.S. that hold “FAFSA Completion Nights,” where guidance counselors and specialists assist students and their families with their applications.

Filling out the FAFSA form — and gaining access to financial aid — can open the door to a college education for many low-income students who may have thought college wasn’t an option. While national, state, and local efforts show promise in raising completion rates, more targeted efforts to low-income students can help these students get the aid they deserve and make the decision that’s right for them.