A Life Sentence Transformed Into a Life’s Work: An Interview with Chris Wilson

At 17 years old, Chris Wilson was sentenced to life in prison. Now 41, he recalls that moment and says, “It was like receiving a death sentence.” But after 16.5 years in prison, he turned his life around. And in the eight years since his release, he has become an author, entrepreneur, philanthropist, and advocate for incarcerated individuals in America. For Second Chance month, which was created to draw attention to challenges faced by formerly incarcerated individuals, I had the pleasure of speaking to Wilson about the impact that the Second Chance Pell pilot program had and the impact that lifting the ban could have.

Wilson points out that society often labels incarcerated individuals as “monsters” who are beyond redemption. But all too often, important questions aren’t being asked. “This monster that you described, how many times has society failed this person before the crime was committed? How many foster homes has this person bounced around? How many times was this person abused? How many times have we failed to provide services to help this person? We don’t talk about that, but we’re quick to label this person a monster,” he says.

According to Prison Policy Initiative, incarcerated individuals are more likely to come from low-income backgrounds. Wilson shared his own experience as a young Black child growing up in a low-income community in Washington D.C. and the trauma that accompanied it. “My neighbor was murdered and I had to go to school the next day. There were no school counselors at my school to talk to. I couldn’t do my schoolwork that week. And things like this happen every day in Black and Brown communities.” At this time, P-12 policy doesn’t provide adequate social-emotional support to students who need it. Instead, those students are over-policed in schools and eventually pushed out — resulting in the school-to-prison pipeline.

So, from an early age, society repeatedly fails communities of color, and the culmination is an overrepresentation of people of color in prison. “The system is designed to punish and oppress,” Wilson says. And once these individuals are released, there are few opportunities available to them. They “check the box,” indicating that they have served time, and experience the “collateral consequences of incarceration.” Oftentimes, difficulties of finding work after release increase recidivism. However, studies show that a college degree or even some college greatly reduces people’s likelihood of returning to prison.

After realizing that he would live out his life incarcerated, Wilson spent three days in his cell, writing goals of who he wanted to become, and the steps he needed to take to be released from prison. He decided that the first step toward achieving those goals was to educate himself. “That was the genesis of The Master Plan,” he said. He got his GED, became a Rattcliffe Scholar at University of Baltimore, got his bachelor’s degree in sociology and taught himself to read, write, and speak three different languages (Spanish, Italian, and Mandarin). Over a 10-year period, his petitions for release were denied five times. The sixth time, he told the judge what he had accomplished, and the plan that he had crafted for his life after release. She told him, “I’m going to give you a shot. But you’ve got to finish the plan.”

Because of the 1994 Crime Bill, incarcerated individuals have been banned from receiving Pell Grants to pursue postsecondary education. As a result, the number of in-prison education programs available has dropped significantly — from about 350 in the early 1990s to about 12 now. However, thanks to continued bipartisan support, 67 sites have just been identified to participate in a new Second Chance Pell program, bringing the total up to 130. Now, people like Wilson will be able to benefit from taking classes and earning their degrees. He speaks about how fortunate he and his classmates were to have that opportunity, and how, as a result, they got their degrees and are “doing well out in society.” He adds, “About half of us went back to get additional degrees. And that’s just a good return on taxpayer dollars.”

Since being released, Wilson has started multiple businesses and is currently partnering with American Prison Data Systems to provide incarcerated individuals with tablets, free of charge. With tablets, people can contact their family members, use educational apps, or even learn to code. He is also working on a curriculum for The Master Plan, so that incarcerated people can use his book as a blueprint to build their own plan and reach their goals. “And now I tell people, you can set goals for yourself. You can educate and discipline yourself, and you can achieve those goals. I am a walking example of it.”

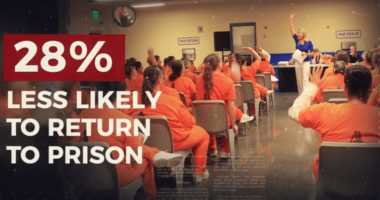

Right now, there are 2.3 million incarcerated people in the United States. Based on a study sponsored by the Federal Bureau of Prisons, people who are able to participate in educational opportunities while incarcerated are significantly less likely to return to prison. Reinstating Pell Grants for individuals who are incarcerated will offer a chance to pursue higher education, preparing them for return to life outside of prison, and providing opportunities for higher paying positions, and reducing the probability of recidivism. The new sites identified to participate in the Second Chance Pell program are a constructive start toward building the change necessary to rehabilitate individuals returning to society after incarceration. Lifting the ban on Pell Grants provides incarcerated individuals with a college education and possibilities for a better future. Every person deserves that chance.

Crystal Amuzie is a senior at the University of Maryland and has been a communications intern at Ed Trust during fall 2019 and spring 2020.