Guess What? There’s Already Under-Representation in School Curricula

A contentious debate about representation in our nation’s school curricula has been rumbling — and it goes beyond the current focus on the AP African American Studies course. Although the College Board curriculum gives nods to Colin Kaepernick and Black feminism, by and large, advancements in curricular diversity and intellectual rigor have been slow and incomplete.

Most schools in the U.S. do not have a curriculum that reflects the diversity of their students’ backgrounds or explores a diversity of perspectives over our complex American history. It should be no surprise that the current kerfuffle is over a course that, because inequities in access to AP courses exist, will be unavailable to most high school students, during a month where many students may be learning about Black history for the first time this year, in a system in which most history classrooms devote only 8% of total class time to Black history.

Publishers, state boards, districts, and educators have put in a lot of work in recent years trying to increase representation in curricula, but there is still much more to be done to provide all students with a diverse and intellectually rigorous schooling experience that will prepare them for college and beyond. And it starts in grade school.

Modest Increases in Representation

Books for children and young adults have come a long way in terms of whose voice is on the page since the Children’s Cooperative Book Center first assessed authorship in 1985. The number of Black authors and illustrators grew from 18 in that first review (less than 1%) to 315 in a 2021 review (9%). In a recent Ed Trust review of 300 English Language Arts books, whose findings will be published this spring, 11% of books included at least one Black author or illustrator. These proportions are still far from the representational equivalent of Black students in U.S. classrooms (about 15%). That share of the children’s book space is put into clearer context when compared to White authorship. In our study, we found that White creators wrote or illustrated 6.6 times as many books as Black creators.

This imbalance affects which people and groups are the subjects of books. Although racial diversity in children’s books increased steadily since 2014, the gains are small. Between 2019 and 2020, the number of books about racially diverse characters or subjects grew only 1% to 30% total. In a sample of ELA books, we found that about 33% (100 total books) feature an individual who is either Black, Asian, Latino, Native American, Jewish, Middle Eastern, or mixed race. Unfortunately, even modest gains may reflect a peak rather than a trend. In an analysis of children’s best sellers, WordsRated found that that a steady increase in diversity quickly reverted between 2020 and 2021, when the percentage of Black characters decreased by 23%.

Limited Improvement in Representation

Most discussions of who gets represented in curricula often end at arguing for including a greater range of people on the pages of books. We should set our sights higher by examining how groups and perspectives are represented when they are included. The how is very concerning.

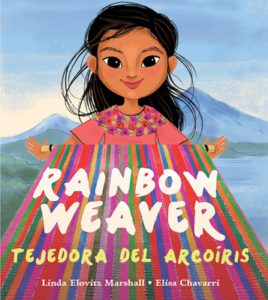

More than half of the books in the Ed Trust study depict groups of color in limiting ways, often by using stereotypes, by portraying groups as negative or deficient, or by uncritically portraying groups as lesser than or dependent on others. This type of portrayal can sometimes seem obvious, like in Bobbie Kalman’s Explore series, which introduces primary-aged students to the continents by portraying the native people of those continents through distinct and superficial comparisons, leaving readers with the impression that Africa and Asia are overpopulated and underemployed. What’s more, negative and deficient depictions of groups of color can also appear in otherwise powerful and engaging books. For example, Books like Ada’s Violin and Rainbow Weaver feature rich, complex, characters who overcome great odds, but authors sell character growth in these “treasure from trash” stories by heavily emphasizing harms and deficiencies in the character’s culture, community, and environment.

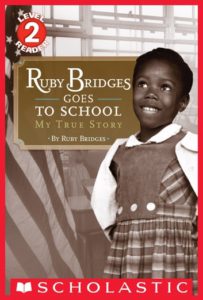

The study also considered how historical events and social topics are discussed in children’s books and found that over 80% of books included such events or topics in limited ways. Most often, that limitation took the form of sanitizing the issue by clearly leaving out or minimizing an unfavorable aspect that would be key to understanding that issue. For example, Ruby Bridges Goes to School minimizes the structural aspect of racism by framing legal segregation as simply a problem of people “thinking black people and white people should not be friends.” When complex issues of our collective past are glossed over in this way, children are robbed of the language and framework for understanding our collective past and present.

In general, children’s books often discuss racism as a problem that was solved during the Civil Rights Movement, thanks to figures like Rosa Parks and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Modern social issues are usually focused on an individual figure or character’s struggle and solutions that rely on that same individualistic response. Similarly, Black history is often centered on stories that focus the reader on individual perseverance against irrational hate, disconnecting racism from its embeddedness in institutional practices, laws, and policies.

And curricula are about to get even more sanitized. At current count, 18 states limit how race and gender identity are discussed in schools. The justification for censorship in these states is that education has somehow gone too far — that K-12 education has too much diversity, that it contains too many perspectives, especially those that conflict with conservative rhetoric.

In our upcoming report, we include a tool to assess representational balance in children’s books. If we are to course correct and return to increased and improved representation, we must begin with a better understanding of where diversity in curriculum stands.

This is a starting point for a collaborative relationship between parents, students, and schools. The Education Trust-Tennessee has had incredible success empowering parents and students to advocate against censorship and in favor of a rich and complex study of history. Amid all the political bluster about “parents’ rights” as a means to push for censorship and exclusion, there needs to be an equally loud voice of parents and caregivers who actually want their students to be exposed to people and characters from diverse backgrounds and cultures. Only then can we achieve parity and inclusiveness.

Sign up to be among the first people to receive our upcoming report on under-representation in school curricula here.