The Bans on Critical Race Theory Are the Latest Attempt to Legislate Ignorance

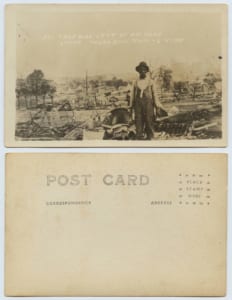

One hundred years ago this week, a White mob massacred Black residents in the Greenwood neighborhood of Tulsa, Oklahoma, ending generations of Black wealth-building that has yet to recover. But if lawmakers in a number of states and a growing chorus of conservative critics of “critical race theory” have their way, students might learn the facts about the Tulsa Massacre, but not the direct connection between the demise of Black Wall Street and current racial wealth gap. The same would happen when it came time to learn about Indian Removal: Students would learn the facts, but without fully understanding the relationship between an attempt at ethnic genocide and the plight of Indigenous Americans today.

This extended learning helps students digest history in the context of current events, develop critical thinking skills, and distinguish between the impact of individual racist acts and systemic racism. But lawmakers are actively attempting to rob students of the chance to do this deeper learning in an attempt to “shield” White students from what students of color so often face on a daily basis in schools across the country — the realization that America is not yet what it purports to be, the burden of calling America to task for the ways in which it has not lived up to the promise of its ideals, and the weight of coming face to face with the hard truths of America’s unfinished journey.

America’s story is rich and complex — exemplifying strength, creativity, courage, progress and possibility. It is also a story of unspeakable brutality and cruelty, hatred, forced enslavement, displacement, and designed economic disparity. Attempts to disentangle who we are as a country from the racism present from our very beginning just to ensure students hold fast to an incomplete narrative about America render students ignorant of important truths and less able to shape the path forward toward a more just future.

Not to mention the implications for those accountable for teaching those truths. As lawmakers move to assuage the discomfort of White students, their actions limit educators’ ability to teach even the history standards in their own states. Tennessee Social Studies Standards, for instance, require teachers to teach about a variety of topics related to African Americans in America, ranging from the slave trade pre-1619 to contemporary times from 1970s to the present. Teachers also are required to help students learn about the annexation of Hawaii, compare the ideologies of former presidents like Woodrow Wilson, Theodore Roosevelt, and William Taft. But while they can teach students about these leaders’ doctrines, they have to deny students the opportunity to explore underlying beliefs about what Wilson called the “Negro problem.”

In Idaho, legislators not only moved to control what students can learn, but teachers’ professional learning too. Negotiations around teacher salaries stalled when GOP legislators refused to fund the teacher salaries budget unless a provision was made to ensure teachers would not advocate for “social justice education.” Lawmakers eventually approved the budget, but not before holding it up to discuss a ban on teaching critical literacy. Think about this: In a country where children are taught a pledge of allegiance that includes the words, “with liberty and justice for all,” a state’s leaders held up the budget that supports the very people charged with the task of teaching that pledge.

In each of these cases, both teaching and learning are rendered incomplete. And given what we know about why educators of color choose to stay or exit the teaching profession, one can only imagine the impact this will have on policymakers’ attempts in these states to recruit and retain Black and Latino teachers.

The irony is that legislating ignorance has always been part of Black educational life in the United States. Black and Brown people have always had to steal their education. In his book, Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching, Jarvis R. Givens shares, “the enslaved had to gain their education by ‘snatching’ learning in forbidden fields,” because this country understood education made a person unfit for subjugation. When we fail to fully teach these historical realities, we risk repeating them with far-reaching effect. Not only are Black, Native, and Latino children once again having to “snatch learning,” all children will be forced into fields of ignorance — ostensibly to protect the sensibilities of those who might find the truth discomforting. Now, lawmakers are pushing the false idea that a good citizen is one who walks in the blind acceptance of American goodness without acknowledging the complex truths of our unfulfilled promise because anything less is tantamount to hate.

The murder of George Floyd one year ago intensified calls for culturally relevant curriculum to open the coffers of learning to be more inclusive of the full breadth of America’s story. And rightfully so: Early Ed Trust analysis indicates that 66% of authors in curricula rated as “high quality” are White, which is more than double the representation of all other racial and ethnic groups combined. Similarly, there’s been a push for educators to adopt the premise of critical race theory, which originated in legal studies. The lens of critical race theory requires placing the events in our country within the framework of the racial dynamics at work within every aspect of our society.

Educators use this framework to deepen students’ critical thinking skills by asking them to probe the singularity of the perspectives being advanced in our history. Students ask questions about missing voices; look under our historical hoods, so to speak, and challenge the power dynamics at play when events are slanted toward an Eurocentric point of view. Educators have the opportunity to build students analytical, evaluative, and critiquing skills in ways that go beyond just learning the basics. Too often, students are taught history that is devoid of its impact on Indigenous communities, formerly enslaved communities, and other communities of color. And they are fed a steady diet of factoids without the opportunity to consider the far-reaching implications on current events.

Truth be told, legislative attempts at narrowing the curriculum to alleviate White discomfort demonstrate the very essence of what assuming a critical lens is designed to foster. Without such lens, for example, students may learn …

- Reconstruction was a 12-year period right after the Civil War, but not about how the laws used to end that period have disenfranchised Black voters to such a degree that there was not another Black senator elected until 1967.

- The GI Bill opened the door for soldiers returning from WWII to earn college degrees and build wealth, but not about the

compromise President Roosevelt had to make, which excluded Black soldiers in order for the bill to pass Congress.

compromise President Roosevelt had to make, which excluded Black soldiers in order for the bill to pass Congress. - Redlining was a discriminatory practice used in the housing industry, but not about how such practices have led to deep inequities in how public schools are funded.

- Early Americans made groundbreaking advances in science, but not about how enslaved women were used as subjects without anesthesia because enslavers believed they were subhuman, couldn’t feel pain, and therefore lacked feelings.

Author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie talks about the danger of a single story; the lens of critical race theory gives educators the tools they need to help students disrupt the single story and build the very academic skills colleges and employers require.

Shutting off access to current events as means of ensuring students will only see America through rose-colored glasses is not only historically inaccurate, it is irresponsible and will jeopardize students’ ability to function in a global society and compete with students whose states allow and expect their students to walk away from 13 years of formal schooling with broad deep knowledge about who we are as a country.

Our nation will never move forward with legislators using their power to emotionally protect one group of students while they intellectually disenfranchise them all.