In Passing the Baton to the Next Champions for Equity

This is a speech delivered at the PIE Network’s Annual Meeting earlier this month.

I’m something of a newspaper junkie. When my morning Washington Post and New York Times arrive around 5:15 a.m., I’m up, coffee in hand, poring through the day’s news.

Reading those papers isn’t as pleasant as it once was.

Some of that, of course, is about the current election — both for what is being said and for what isn’t even being talked about.

But there are also those faces — the faces of the Syrian children. Trapped first in Greece. Then in Hungary or Turkey or Lebanon or Jordan.

Haunting faces of beautiful children whose lives and potential are being horribly and brutally squandered while the world — and certainly the U.S. — mostly just watches.

I don’t know about all of you, but I am haunted by their faces. Each and every one a stark reminder of our inhumanity. Of our essential numbness to even colossal human tragedy.

But you know, I’ve got to say that I am haunted even more by the children whose faces are not in the morning paper.

The homeless kindergartner with mismatched shoes who sleeps with his father in a car in the Wal-Mart parking lot, and who makes it to school — if he makes it at all — 30 to 40 minutes late.

The third-grade girl whose one dress — with ruffles all around — has grown gray and tattered because, while her mom tries ever so hard, there is no running water in the Colonia.

The sixth-grade Appalachian boy who got two “unexcused absences” last week and risks being suspended from school for staying home to care for his meth addict mother and baby sister.

The 11th-grade boy who returns to his high school from the “juvie school” determined to start all over again, but worries that the adults in the school won’t see him as much for what he is trying to be as for what he was.

These are the kids whose faces are not in the morning paper — unless, of course, there is yet another shooting.

That our country allows so many children to live in such dire circumstances is appalling. After all, we remain the richest nation on earth but are choosing — yes, it is a choice — to tolerate the second-highest child poverty rate of any country in the developed world.

But here is the thing: How we advocates respond to the effects of that choice — and to decades of racism with similarly corrosive effects — is a choice, too.

Right now, our education system in this country is organized to exacerbate the challenges kids bring with them to school. Indeed, we take the kids who come to us with less and turn around and give them less in school too. We spend less on their education. We expect less from them. We systematically teach them less. And we assign them our least experienced, least well educated, and least effective teachers. And when they respond rationally by just not coming to school — either out of boredom or frustration with texts they can’t read — we suspend them and tell them not to come to school. Then when they don’t perform so well on standardized tests, who gets blamed? The parents. The kids. Their race. Their culture. We never ever talk about what our system does.

These practices are so long-standing that many folks within the education system can’t even see them anymore — much less see clearly the children that they so disadvantage.

That’s where we advocates come in. We can see the inequities. We can see the children.

But that is where our choices become critical.

We can either choose, as some of us in this room have, to believe that the systemic improvements on which we have been working so hard — the common standards and aligned assessments, the teacher evaluation, the expansion of choice — will raise all the tiny boats that need raising. Or we can be honest in acknowledging that anything built on such a deeply inequitable foundation will never, by itself, achieve our aims.

If we have learned anything during the last 25 years, it is this: Generic improvement strategies will not, by themselves, get all children where they need to go. Each of those levers we work so hard to put into place must actually be pulled on behalf of vulnerable children.

What does that mean?

If we work on teacher effectiveness, we have to work on equitable access to effective teachers. There is nothing in our history as a country suggesting that if we just know who the most effective teachers are, low-income kids or Black and Latino kids will magically get more of them.

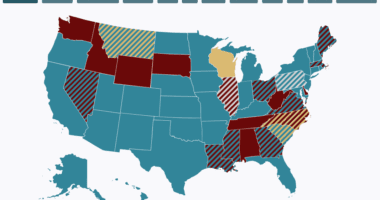

Similarly, common and high standards are a critical lever for rooting out long-standing differences in what we expect of different kids. But as our recent analysis of actual classroom assignments shows, the standards themselves can’t get that done. Implementation efforts must acknowledge the different places that different teachers and schools are starting and stagger support accordingly.

As for efforts to get more funding into the system — or more, even, into high-quality charters: Working on that without putting greater funding equity at the heart of our efforts won’t get the kids who most need our help where they need to get.

And our efforts to accomplish all of this will be vastly more successful if we don’t do this work alone, but join in coalition with the many grassroots organizations representing the parents of the children whose lives we want most to affect. Their insights have been missing from the table for too long. Yes, such coalitions are messy and sometimes slow. But houses built on a stronger foundation are more likely to weather the strong storms we will continue to face in years ahead.

200 education and civil rights advocates come together to go deep on #ESSA #ESSABootCamp @EdTrustWest @EdTrust @NatUrbanLeague @NCLR pic.twitter.com/O067mdV24y

— Ryan J. Smith (@RyanSmithEd) October 20, 2016

As some of you know, I do a fair amount of white water kayaking. Over the years, a lot of folks have asked why I would want to spend my weekends in much the same way I feel on many of my weekdays (especially the days I spend with Congress) — strapped into a small boat, being dragged downriver upside down with my head bouncing off rocks.

Here’s why: In white water boating, there is a maneuver you learn — called a hip snap — that, once mastered, enables you to flip your boat back right-side up. It’s crazy-hard to learn, because everything about it is counterintuitive. But when you master it, you really can get right-side up even in the middle of rapids.

And for the first 10 years or so of my work in education, I was constantly looking for the equivalent of a hip snap — that thing we could do that would get the system focused far more sharply on the kids it was systematically underserving.

I eventually learned, as many of you have, that there is no hip snap. It’s a much longer slog, with enormous progress in some years and a return to old battles in others. It started to feel more like distance kayaking, in fact, so I got one of those.

But it is clear to me now that this work of ours is actually a relay. Just as I took the baton from the equity warriors who preceded me and who were so generous in sharing the wisdom they had accumulated, it is nearing time for me to pass the baton to you — which I do, by the way, in full confidence that you will take the work in places we never dreamed it could go.

As you run your leg of the relay, though, please remember this: At the finish line, there isn’t a tape. Standing there, instead, are:

The kindergartner in mismatched shoes.

The third-grade girl in the tattered dress.

The child who takes care of his addicted mom and baby sister.

And the boy who needs us to see the scientist he wants to be instead of what he was.

They are who matter more than even the sweetest policy victory ever will. And we must judge our work not by bills passed or enemies vanquished, but by whether it improves the trajectories of their lives.